I’m way behind on my race reports, with Swiss Peaks, Quad Dipsea, Way Too Cool, Miwok, and Dipsea still in the queue. But I’m going to jump that queue and write up Western States, because…well, it’s Western States. This is, after all, where modern ultrarunning began, back in 1974 when Gordy Ainsleigh ditched his horse and ran the 100 miles from Squaw (now Olympic) Valley to Auburn. The sport has grown exponentially since then, and there are harder and more beautiful 100-milers, but Western States is still The Show. Along with its younger cousin, Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc, it’s where the best in the world go to prove they’re the best. For the rest of us, it’s a Holy Grail we strive to get into for years — kind of like the Boston marathon for road runners, except that States is a thousand times harder to get into. All of which is to say: when you finally do it, you give it its due.

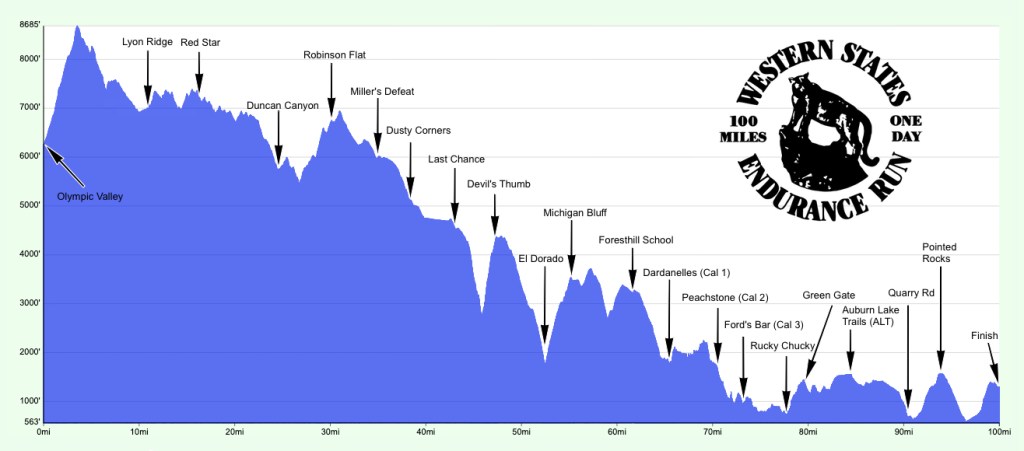

States is a point-to-point race that begins in Olympic Valley near Lake Tahoe and ends on the Placer High School track in Auburn. Along the way, it climbs in and out of the American River canyons multiple times. It’s net downhill, with around 18,000′ of climbing and 23,000′ of descending. This ensures a wide range of conditions, from the cold, snowy high country to the hot and dusty canyons below.

Although a handful of elites run blistering times – the course records going into this year were 14:09 for men and 16:47 for women – most entrants have other goals. Two cutoffs in particular focus most runners’ minds: the 30-hour cutoff for official finishers, who receive bronze belt buckles, and the 24-hour cutoff for silver buckle finishers. The latter was my main goal for this race.

If you’ve heard of Western States, you’ve probably heard about the lottery. In the race’s early years, the sport of ultrarunning was so small that getting in was easy: you applied, you got in. The number of starters was small but grew quickly: 1 each in 1974-76, 14 in 1977, 143 in 1979, 369 in 1984. That last number is significant because, in 1984, Congress created the Granite Chief Wilderness, which included miles 6-10 of the course. Organized events are not permitted there, but Western States was grandfathered in — with the proviso that the number of runners could not grow. Because that number was 369 in 1984, there it has remained.

This wasn’t a hugely binding constraint even into the 1990s, as ultrarunning remained a fringe pursuit. By one estimate, however, the number of ultra finishes grew from 34,401 in 1996 to 611,098 in 2018 — a 1676 percent increase in 23 years. The sport has accommodated this growth by offering more and more races: an ultrarunner today has more options than ever before. But everyone still wants to do States, and the race cannot grow. The upshot is that in 2023, 7169 applicants vied for those 369 spots. But really, because a lot of entries (96 this year) are reserved for Golden Ticket winners, previous top-ten finishers, and other special categories, those thousands of aspirants are chasing fewer than 300 spots. Those aren’t good odds.

So how does an aspiring Western States runner get in? The same way you finish a 100-mile race: persistence. Every year, you run one of the qualifying 100k or 100M races. Every year, you enter the lottery. And every year, you see your number of tickets grow. Each applicant receives 2^(n-1) tickets, where n is the number of years you’ve entered the lottery without getting in. So you get one ticket in year one, two tickets in year two, four in year three, eight in year four, sixteen in year five, and so on. Eventually, if you can keep running and qualifying long enough, you should get in: this year there were five applicants with nine years’ worth of tickets (256), and they all got in. Congrats to them, but nine years is a long time to wait.

Fortunately, I didn’t have to wait so long and got in last December with only sixteen tickets. Despite my long preamble, this wasn’t the fulfillment of a lifelong dream. I’d done the Memorial Day training camp multiple times and knew the last 70 miles of the course well. I didn’t feel a burning need to run them again in a race. To be honest, I’d long suspected that Western States is like that ice-cream shop you find in every college town — you know, the one with the line stretching around the block, whose main selling point is that everyone wants to get in. But then, I’d felt that way about Boston until I first ran it in 2014 — the year after the bombing — and was blown away by the collective “Boston Strong” energy. Maybe States would be like that. In any case, after five years of waiting, I’d finally get to see what was behind all the hype.

I’d like to say that, when I got in, I dropped everything and began training for the race of my life. But for various reasons, I ran very little over the winter and didn’t start training in earnest until mid-March. This was good enough for a solid performance at the Miwok 100k on May 6, followed by the training camp on Memorial Day weekend and the Dipsea Race on June 11. I wouldn’t say I was in amazing shape, but I felt ready by the time States rolled around.

Megan had agreed to pace me the full allowable distance, from Foresthill (mile 62) to the finish. Because point-to-point races create some logistical challenges, we’d enlisted my friend Dean to help crew. I was glad for the support: knowing I’d see them at Michigan Bluff (mile 56) would give me something to look forward to, and having them around thereafter would get me through the night.

I headed up to the Tahoe area a few days early and camped at the Prosser Family campground. It’s a nice spot, not far from Olympic Valley, and quiet during the week. I did a couple of easy runs and met some nice people on the trails, including a man in his 70s who’d run the Dipsea seventeen times and had just crewed at Miwok — small world. Otherwise, I just lounged around and occasionally walked down to Prosser Lake to see the bald eagles.

Although I was purposefully relaxing, I wasn’t relaxed. I’d been immersing myself in stories, news and podcasts about Western States, all of which was putting me on edge. I told myself it was just another 100M — but if that was true, why was everyone treating it like such a big deal? Try as I might, it was hard to tune out the hype. Still, despite being nervy, I slept pretty well at Prosser, even on the crucial night-before-the-night-before. It’s a truism that the penultimate night before the race is the important one, although I wonder if this is really true or just something runners say because the night before often sucks. Regardless, I felt well-rested on Friday, when I headed to Olympic Valley for check-in.

As I drove into the valley and saw the peaks I’d be climbing tomorrow, I couldn’t help smiling at the sight. Maybe Western States isn’t the most spectacular course in the world, but right now, those peaks were good enough for me.

Olympic Village was a scene, with runners and pre-race activities everywhere. Check-in was a bit involved, with one line for bib pickup, another for swag, and a third location for drop bags. After getting my bib, I ran into my friend Garret and his pacer Caveman in the swag line. They invited me to join them in the queue, but I wanted to ditch my drop bags, so I headed there first before returning to the line. By that time, Garret and Caveman had left, but I ran into Jenny, a Berkeley Running Club (BRC) acquaintance, standing in line. As I’d realize throughout the weekend, you run into a lot of familiar faces at Western States, even if you’re an introvert like me.

I headed to the events plaza for the pre-race briefing and ate lunch there with Garret and his friend Tod while waiting for the briefing to start. Gordy was there — he’s always there — dropping pearls of wisdom. I got a text from my college friend Tantek, who’d just done a Broken Arrow race here and was sticking around to crew for a friend. I hadn’t seen him in fifteen years, so I went to find him and spent a few minutes catching up. A strange coincidence, but you see a lot of people at Western States.

I’m not a huge fan of briefings, which are usually pretty redundant, but this one was fine. I appreciated the nods to all the people who make this race possible — the park service, trail workers, volunteers, and so on — and Craig Thornley, the RD, had some useful things to say. There’d be discontinuous snow for the first 20 miles of the course, with about ten total miles covered in snow. There’d be a lot of water and mud where the snow had melted. On the plus side, this would be a cool year, with highs in the 80s in the canyons. All good to know.

After the briefing I headed back to my camp, arranged my running stuff for the next morning, and tried for an early night. I smoked a lot of weed, trying to make myself sleepy, and managed to nod off around 9:00pm. I’d set my alarm for 2:45, but unfortunately I woke up at midnight and couldn’t fall back asleep. Oh well: not exactly surprising, given my nervous energy, and I’ve done worse. At 1:00am I accepted the inevitable and just got up.

Since my involuntary early start left me with lots of time, I read the news while drinking coffee in my tent. A big story had just broken: Yevgeny Prigozhin had taken over Russia’s southern military command in Rostov-on-Don. That sounded like a pretty big deal, but I didn’t have time to absorb all the details. Dean was going to walk me up Bath Road in Foresthill, so I made a mental note to ask for a briefing when I saw him. If anyone would know the details, he would.

At 3:45 I headed to the start, eating an avocado sandwich on the way. Race morning check-in was mandatory, and I wanted to make sure I had time to use the bathroom and put on sunscreen before the start. As it turned out, check-in consisted of flashing our bibs while walking into the start area, so I went back to my car, put on sunscreen, ditched my warm jacket (it was 40F), and returned to the start.

By the time I entered the starting corral, I was at the back of the pack, which was fine. Everyone says the race begins at Foresthill: by then, you’re done with the high country and canyons and can really run. My plan was to take the early miles easy to spare my legs, then kick it into gear at Foresthill. That’s a gamble, as I’d have to count on running fast late in the race, but starting fast is a gamble too.

At 5:00am we were off. We began the long initial climb to the Escarpment, about 2500’ in three miles. I didn’t attempt to move faster than a brisk hike, and since I was back in the pack, neither did anyone around me. I stopped a couple of times to take pictures as the sun rose above Olympic Valley. I felt happy to be out here, finally doing the race, and comfortable with my pace. That said, when I turned around and saw far fewer runners behind me than ahead of me, I got a little scared. I’m not a back-of-the-packer, and while I knew that many miles lay ahead, this just felt weird. I’ve never thought about aid station cutoffs before, but I started wondering if I should. As if in response, a man next to me — Gene Dykes — started talking about how he was running this year to become the oldest finisher ever. When you’re pacing a 75-year-old man who might finish before the 30-hour cutoff, you know you’re not burning up the trail. (Sadly, Gene wouldn’t finish, getting pulled at mile 70 at 2:40am.)

At least my watch thought I was moving fast. I still use an ancient Garmin Fenix 3, which has a battery life of only fifteen hours in normal GPS mode. I can get thirty hours by putting it in Ultra Trac mode, but the accuracy sucks. Sure enough, my watch clicked off mile two in seven minutes and mile three in six, even though I was probably doing 17-minute miles up this hill. Since a wildly inaccurate watch is worse than no watch at all, I turned off the GPS. From here on out, I’d be flying blind, with no information beyond the time of day.

After a few miles we left the long fire road and crossed a snowfield, just in time to see the sun rise. The snowfield climbed gradually for a while, then took us to a steep single-track ascent. More spectators lined the course here, and I saw Jack and Ken, also Bay Area runners, cheering me and the other racers on. I soon reached the Escarpment, the highest point in the course, where cheering spectators created the loudest “scream tunnel” I’ve seen since the Wellesley corridor at Boston. I passed through and was on the other side.

Clearing the Escarpment feels like a milestone, not only because you get to stop climbing but also because you can finally see the course stretching ahead to the west. I stopped to take a few pictures. Once I started moving again, I perceived the downside of my start-slow strategy. We were now on a downhill single track, and the runners ahead were moving none too fast. I hate being stuck behind others on downhills, but having gotten myself into trouble trying to pass in these situations — I sprained an ankle at IMTUF in 2018 — I decided to accept it and move with the pack. There were a lot of miles left, after all.

Before long the trail disappeared beneath undulating, hard-packed snowbanks, and the bottleneck got worse. I didn’t find the snow hard to traverse, but the hundred or so people in front of me apparently did. Instead of just sliding down the snow on their feet or butts, a lot of runners were tentatively picking their way through the snow as if afraid to fall. They’d stop at the edge of a downhill to find their footing, and the delay would halt the entire line, much as a minor slowdown on the highway can ripple back and jam up traffic for miles. The RD had said that some people move better on snow than others, but seriously, who moves this slow? I endured it for a while but eventually couldn’t take it any more and began passing people along the sides of the snowbanks. This required some effort, since the sides were both sloping and less hard-packed than the crest. I’d slip and catch myself, burning some extra energy every time. But eventually I’d passed enough people that I could run at a pace that seemed normal. Huge relief.

I later heard people complain about the snow, but I kind of liked it. It was slow compared to an open trail, but it added variety and accentuated the alpine feel. And anyway, the snow wouldn’t last forever — we’d have plenty of dry trails to come.

After about two and a half hours, I finally stopped to pee and put away my light jacket. I’d been wanting to for a while but didn’t want to get caught by the pack and stuck again. A lot of runners passed me while I was stopped, but fortunately not enough to create any more bottlenecks.

I ran through the first aid station at Lyon Ridge (mile 10.3), as I hadn’t used any water or food yet. The next few miles were open ridgeline, and I enjoyed seeing the snowy landscape on this beautiful day. The course offered expansive views of the mountains to our south and east, but although the sky was clear, the air was hazy with smoke. The RD had mentioned that the forest service was doing a controlled burn today, which I could both see and smell.

When I arrived at Red Star Ridge (mile 15.8) I saw Garret, who’d arrived just before me. I asked how he was doing, and he said he’d felt better. He’d had a nagging hamstring injury going into this race but didn’t elaborate on whether that was the problem. He asked if I’d had my usual OD of marijuana and beer the night before, and I confessed that I’d smoked a lot. Another runner overheard me and volunteered “I was so stoned last night!” Good to know it’s not just me.

I gulped some ginger ale and filled a ziploc bag with potato chips, then headed out. I loved the next nine-mile stretch to Duncan Canyon (mile 24.4). It was mostly downhill or gently rolling, on a ridgeline covered with pine trees and occasional snow. I thought, as I usually do, about how lucky I was to be out here. Not everyone has the fitness, leisure time or disposable income to do something like this, and I think it helps to be grateful for what I have. The miles to Duncan Canyon flew by.

As I entered the aid station, I heard someone calling my name. It was Greg Lanctot, the Pacific Coast Trail Runs race director, whom I hadn’t seen since probably 2019. He seemed surprised by my appearance, saying only “The hair!” I haven’t gotten a haircut in over two years, and I guess it shows.

I asked a volunteer to refill my hydration pack bladder. I don’t love using the bladder and prefer to rely on front-mounted soft flasks. But I’d had a bad experience at Miwok: with no counterweight in the back, the flasks bounced on every downhill, eventually bruising my ribs. I didn’t want to deal with that here, so I stuck with the bladder instead.

I’d made myself an extra-large ice bandana for the race, but there didn’t seem any reason to use it just yet: it was still cool here at the aid station. Just a few minutes after leaving, however, it began to get hot. We were now descending into Duncan Canyon, and the temperature rose noticeably as we went down. This was the first of the canyons, and the only one I’d never run before. The trail descended gradually for two miles until it hit Duncan Creek. There was a rope line to help us across the creek, which was about thigh-deep. I waded through the cold water, which felt pretty good, and continued up the other side.

The climb from Duncan Creek to Robinson Flat was long, hot and hard. I passed a few runners along the way, who agreed that this was comparable to Devil’s Thumb. When I left the last aid station, I thought I might realistically get to Robinson Flat by noon. That was looking less and less likely as I trudged up this never-ending hill. I was having trouble with my water, too: for some reason I couldn’t suck it through the hose. I wondered if the volunteer had messed something up but eventually realized the hose was just kinked. After straightening it out, it worked fine.

It got cooler as we climbed, and as I approached Robinson Flat, the trail once again disappeared under snow. I was glad to hear the aid station in the distance, which meant a change of shoes and a return to familiar terrain. I cruised into the aid station and said hi to Jenny, who was waiting there for her runner. It was a relief to take off my waterlogged shoes — we’d had several creek crossings in the last few miles — and to replace them with clean dry ones. I grabbed the two smoothie flasks I’d left in my drop bag, filled my bandana and hat with ice, and continued on my way.

It was after 12:30 when I left Robinson Flat — more than an hour behind the race’s suggested 24-hour pace. This didn’t worry me too much, as those pace guidelines seemed off to me. They assume considerable slowing throughout the race: for example, they imply a 13:40 pace from the start to Michigan Bluff (mile 56) but a 15:20 pace from Michigan Bluff to the finish. That seems crazy to me, since those first 56 miles are way harder and less runnable than the last 44. In any case, I was committed to my strategy: I’d just have to trust that taking it easy now would enable me to run faster later on.

The next four-mile stretch to Miller’s Defeat was mostly downhill on runnable fire road. I wondered if I should be going faster here, but I was still reluctant to push it with 70 miles and two major canyons to go. After a couple of miles I caught up with a guy named Alex, and we chatted about ultrarunning stuff — e.g., the ethics of making your crew wait for hours on the off chance that you’ll have the race of your life — until we reached Miller’s Defeat. I had no reason to stop there, so I wished Alex a good race and moved on. I was grateful for the company, which had really helped the miles fly by.

I ran on autopilot for the next nine miles to Last Chance: a mix of familiar single-track trail and fire road. I noticed that my stomach wasn’t doing great: between the smoothies and apple turnovers I’d grabbed from my drop bag, I was starting to feel queasy. I probably should have stuck with my tried-and-true Gatorade fueling — I’ll go through many packets of Gatorade Endurance Formula during a typical race — but I’d abandoned that approach when I decided to use the bladder rather than flasks. Too bad: with the weight of my jacket, phone and other things in my pack, the flasks were behaving fine. I decided to rely on those for the rest of the race.

I ran into another BRC runner, Brent, at Last Chance. He helped me refill my ice bandana and flasks, and I was on my way. Shortly after leaving, I wished I’d tarried there longer — long enough, at least, to use a porta-pottie. With my guts now churning, I knew I’d have to make a pit stop soon. I didn’t like the look of the woods around me — they seemed mosquito-y — but I knew my window of opportunity would close once I entered Deadwood Canyon. There, I’d find only steep, sparsely covered canyon walls, with most of the cover provided by poison oak.

I ducked into the woods just off the trail and did my business, which proved harder than usual with ice dripping and falling everywhere. As expected, a swarm of mosquitoes descended on me right away. Not much fun, but at least it was done. For good measure, I re-applied Vaseline liberally, still scarred by my chafing experience at Vermont. I was doing ok, but with my clothes continually soaked by melting ice, I didn’t want to take chances.

With my GI system more settled, I began the descent into Deadwood Canyon. This 2000-foot drop to Swinging Bridge would be the most difficult of the day, and I kept my strides short to limit the shock to my legs. Down, down, interminably down: this was hard, and I wasn’t enjoying it. I was relieved to reach Swinging Bridge at the bottom, despite the climb that awaited on the other side.

Up, up, up: the 2000-foot climb to Devil’s Thumb is one of the course’s toughest, along with Duncan and El Dorado Canyons. I was moving slowly, but still passed many people who’d passed me while I was squatting in the woods. This was hard work, but still easier on my legs than the descent. After two miles of climbing, I was relieved to reach the Devil’s Thumb aid station.

Although this wasn’t a hot year, I was still struck by how much warmer it was in the canyons than up above. As I left Devil’s Thumb loaded down with ice, I actually started shivering, my teeth chattering uncontrollably. I was tempted to ditch the ice but figured I’d want it in El Dorado Canyon.

That proved true: El Dorado had lost a lot of vegetation during last year’s Mosquito Fire, and it got hot quickly as I began to descend. This was also a long descent, but less steep than Deadwood and easier on my legs. I stopped briefly for fluids at the El Dorado aid station and began the long climb up the other side.

I was looking forward to seeing Megan and Dean at Michigan Bluff, now only three miles away. And yet, negative thoughts began to creep in. In only nine miles, I told myself, I’d be done with Day 1 of the training camp, which runs from Robinson Flat to Foresthill. Then I’d “just” have to do Days 2 and 3. Those days were hard enough even with a good night’s sleep in between: what would they be like on top of the 62 miles from Olympic Valley? Knowing the course isn’t always a blessing: right now, it merely helped me visualize the long miles to come. What was I doing out here? Whose idea was this, anyway? Every ultrarunner knows these thoughts, and no matter how many times you push through them, they always come back.

I’d been hoping to reach Michigan Bluff by 6:00pm: that was still behind the recommended 24-hour pace, but not by much. But as I climbed, it became clear that wouldn’t happen. 5:50 and still climbing. 6:00 and still climbing. 6:10 and still climbing. But eventually I reached the top. As I emerged from the trees, I saw spectators on the hillside above and heard one of them shout “You’re doing awesome! You look FRESH!” Without looking up, I responded with my best gallows-humor laugh. I guess they found that amusing, as I heard them laughing in return.

I ran into Michigan Bluff and heard the announcer—Victor Ballesteros, though I didn’t know it at the time—call my name. I looked around and saw Megan waiting for me in the street. I told her I wanted to refill my flasks with the Gatorade I’d left with her, so we made our way to their crew spot. I said hi to Tantek along the way, apparently still waiting for his runner.

Dean was at the crew location, along with Garret’s girlfriend Amy and my baby elephant Pasquale. Dean was making me an avocado wrap — one of various foods I’d requested — but my stomach was still feeling queasy, and I wasn’t sure how much I could get down. They’d also brought some noodles and broth, which sounded good right now, and I gulped as much as I could.

I didn’t arrive in great spirits, saying “I can’t believe I’m only halfway done!” and telling Megan I might have to rethink my goals. It was now 6:30, which — as a prominently displayed sign reminded me — was 50 minutes behind the recommended 24-hour pace. Now running on tired legs, my confidence began to crack, and I doubted I could make up the time. Still, the combination of rest, food and friendly faces did me a world of good, and I felt revived by the time I left, eating my avocado wrap and washing it down with a caffeinated GU.

I chatted with a woman from Minnesota I’d been yo-yoing with throughout the race. She was clearly getting through the aid stations quickly, as I’d pass her on the trail and then pass her again a few miles later without ever seeing her pass me. She mentioned that we were behind 24-hour pace, and I said we should still be fine as long as we didn’t slow down. Between the brief rest and the caffeine, I was feeling optimistic again.

The stretch to Foresthill went by quickly. There was one more canyon (Volcano) to traverse, but this felt like barely a speed bump after Duncan, Deadwood and El Dorado. I soon reached the foot of Bath Road, where I expected to see Dean. He wasn’t there, but I eventually saw him further up the hill. The commute from Michigan Bluff to Foresthill isn’t long, but it does involve a shuttle bus, and Megan and Dean had just arrived. We walked up the hill to Foresthill Road as I explained why I didn’t buy the race’s 24-hour guidelines. We then jogged the rest of the way to Foresthill Elementary School as I got my update on Prigozhin’s attempted coup (which was shaping up to be less than meets the eye). I refilled my flasks as Dean ran ahead to alert Megan. As I left the aid station, someone shouted “Love the hair!” Cool; I could use all the support I could get.

Foresthill was a major stop, as I changed my shoes, shorts and shirt. None of this was necessary, but it felt good to get out of my wet and grimy clothes. I also stripped off the arm sleeves I’d been wearing all day and tied my hair back so I could ditch the hat. It was getting cooler, and I wanted to be as comfortable as possible. I slurped down as much noodles and broth as I could while doing all this, and took some rice balls Megan had made for the road.

Dean said he’d see us at Rucky Chucky, which was a welcome surprise. I wasn’t sure if he’d be going there, as it would be late, and getting there required another shuttle ride. But he said he’d like to see more of the race and could bring the rest of the noodles. That sounded good to me: the more I had to look forward to, the better.

Megan and I left Foresthill a little after 8:00, and I said “Let’s go get that silver buckle.” Bold words, given that we were still 50 minutes behind the recommended pace, but I thought we could. As we ran through downtown Foresthill (such as it is), I again heard Tantek cheering me on. I shouted at him to go say hi to Dean, who was just up the road and also knows Tantek from college. “Western States brings people together?” I thought to myself. Is that what makes it special?

We made good time along the paved road, but I did not love the next few miles. Due to a land-use dispute, the course had been rerouted: we’d spend more time than usual on Foresthill Road before descending a steep fire road to the Western States trail. That downhill was my least favorite of the course: without any real switchbacks, it was steep and required a ton of braking. I slowed down along the way to preserve my legs, but I still reached the bottom worrying that I’d blown a quad.

I paused briefly at Cal-1 to top up my flasks, then continued along the trail. We plodded along steadily but slowly. Megan tried, as she would for some miles, to get me to run faster, but I wasn’t having it. I felt ok but worried about that downhill and was still afraid I might blow up if I pushed too hard.

Suddenly I heard someone say “Megan!” behind us. It was Megan’s friend Marie, who was pacing a friend from Chicago. We chatted briefly, but Marie’s runner was feeling good, and they soon left us in their dust. Wow, they are really moving, I observed. Good for them, but it didn’t boost my own confidence.

I stopped to drink some veggie broth at Cal-2 (mile 70.7), then headed down the runnable switchbacks to the American River. We made good time on the descent and soon caught my Minnesota friend, who had left Foresthill before us. “Hey, Minnesota!” I called out. I said she had that silver buckle in the bag, but she expressed doubt, saying her quads weren’t doing well. I wouldn’t see her again.

It was less than three miles from Cal-2 to Ford’s Bar, but even though it was all downhill, it felt long. My thoughts went dark again as I realized I wasn’t making up time: we’d reach Rucky Chucky still 50 minutes behind 24-hour pace. That gap had held constant since Robinson Flat, and I saw no signs it would narrow in the remaining miles.

I wasn’t feeling awful: just not good enough to pick up the pace. I probably wouldn’t have felt so discouraged if I hadn’t set my sights on a silver buckle. I knew I could finish, but that 24-hour cutoff was like a weight around my neck. For some reason, I kept visualizing my least favorite parts of the Day 3 training run, which added to the weight. I told Megan I wanted to cry; I said I was tempted to DNF. I wasn’t about to, but that’s how I felt. Megan reminded me that things sometimes change late in the race.

We remarked on how quiet it was out here. We hadn’t seen another runner in a while. The only sound was our footsteps and the swirl of the American River on our left. We couldn’t see it, except when the trees cleared and the moon glinted off the surface. But we could always feel it, high and roiling from the recent snowmelt.

I saw the lights of Rucky Chucky (mile 78) in the distance. The aid stations here look magical at night — brightly lit oases in the dark — and Rucky Chucky seemed particularly festive as we pulled in. Dean was there and recorded our arrival. He asked how I was doing. I rolled my eyes and said 24 hours wasn’t in the cards.

While Megan filled my flasks with caffeinated Roctane, I ate some of the noodles Dean had brought. He’d microwaved them since we saw him last, so they were still hot-ish and really good. Why is it so easy to eat noodles and broth when nothing else works? Not sure, but I’ve been thinking about how to take noodle soup with me from the aid stations so I don’t have to stand around. I could easily have eaten more but was conscious of the time and wanted to move.

Right now, moving meant taking the boats across the river. In a normal year, runners wade across with the help of a rope line. According to the RD, normal-year water flow here is 250 cubic feet per second. This year it was orders of magnitude higher, at 20,000 cfs. Too deep to wade, too icy and swift to swim. So we strapped on life vests and boarded an inflatable raft that took us across.

We scrambled up the bank and were greeted by strings of colored lights and…bubbles? Someone had set up a bubble machine that was continuously blowing bubbles into the air — a nice festive touch for those with 78 miles on their legs. We pushed through to the fire road that led up to Green Gate.

The hike up to Green Gate was long. It wasn’t super steep, but I wasn’t about to run a two-mile uphill, so I hiked as fast as I could. As we passed a runner and his pacer, I asked what they thought of our chances for sub-24. “Good!” said the pacer, citing the runnable trails to come. Good if you have legs, I replied, and the pacer assured me his runner did. Their optimism lifted my spirits, although I noticed it came mostly from the pacer: the runner just kept walking, silently.

Green Gate was a small but cheery aid station. A volunteer assured me I could break 24 with the runnable miles to come. He also steered me toward some delicious looking tater tots, which I loaded into a ziploc bag. I left feeling even more buoyed: with all these people saying sub-24 was in reach, who was I to disagree?

We finally got off the fire road and onto a familiar single-track trail. I was ready to run, but the trail went immediately up a long, steep hill. I said to Megan “The thing is, this last part is runnable…except for the parts that aren’t.” And in fact, there were some pretty non-runnable parts ahead: a long, technical uphill from Quarry Road to Highway 49, an even steeper and more technical uphill after Highway 49, and a long climb to Robie Point and beyond. All of which meant I’d better log some fast miles where I could.

That seemed to be here, now. The trail leveled off and I started running. Then running a little faster. Then a little faster. I’m not sure if the caffeine kicked in just then, but I was starting to feel better. I kept pushing the pace, thinking I should take advantage of this surge while it lasted. For all I knew, I’d be walking again in a mile.

Except I wasn’t. The more I pushed, the stronger I felt. I’d entered a virtuous circle where running well boosted my confidence, and confidence helped me run. I’d reached a flow state, focused entirely on the trail and my movement rather than the miles to come. When I run this section in the training camps, I’m careful to avoid the poison oak that lines the trail. Now, I was heedlessly running through it: I’d deal with it later; now I had better things to do.

It helped that the trail was a narrow tunnel through the woods. Running along such a trail in the dark gives the illusion of speed, which can energize you and lead to actual speed. Without GPS, I had no idea how fast I was actually going. Megan’s watch logged some 10-ish minute miles through here, and that seems about right. That doesn’t seem that fast, but we were over 80 miles into the race and still walking the uphills. The race’s 24-hour guidelines anticipate a 15 minute/mile pace on this section (Green Gate to Auburn Lake Trails), so I was finally making up time. I told Megan “I’m just going to keep kicking until I can’t.”

We soon hit Auburn Lake Trails (mile 85.2), where we were greeted by Vicky, another BRC friend. I stopped to gulp some Coke and refill with Roctane, but I was anxious to keep moving, afraid I’d lose my momentum. I pushed ahead of some other runners leaving the aid station and quickly left them behind.

I passed sixteen runners in the eleven miles between Green Gate and Quarry Road. The passing took no time at all: I’d see a light in the distance, catch up to it in a few seconds, and just as quickly leave it behind. What was going on?

My conservative pacing had certainly helped. But as Megan had suggested earlier, something often happens to me late in the race. There’s a concept in endurance science known as the central governor theory. The idea is that our brains have a “governor” that prevents us from casually pushing ourselves to exhaustion and collapse. That makes sense: evolution would favor those who kept something in reserve for real emergencies, like outrunning a hungry lion or bear. And the idea enjoys a lot of empirical support. For example, athletic performance suffers from glycogen, sodium and oxygen depletion even when bloodwork reveals plenty of glycogen, sodium and oxygen still in the body. Heat degrades athletic performance long before core body temperatures rise. In such cases, the brain apparently responds to early warnings of scarcity by shutting the body down. Moreover, merely tasting sugar or salt (without swallowing it) or making someone feel cooler (without actually reducing their core body temperature) can instantly produce a performance boost. When the brain perceives that help is on the way, the governor lets up.

As Alex Hutchinson notes in Endure, the most striking evidence for the central governor theory may be late-stage race performance. Runners who have been struggling to move for hours are suddenly able to sprint when they near the finish line. The knowledge that we’re almost done seems to unlock reserves we’d previously been denied.

In any case, I’m a firm believer in the central governor theory, having experienced this late-stage surge many times. It’s not like I was feeling great in those slow earlier miles and deliberately holding back. I’d felt tired and incapable of anything more. But now, in the last 20 miles, I stopped worrying about blowing up. My governor allowed me to push, so I did.

We stopped briefly at Quarry Road (mile 90.7) to top up my flasks and eat a couple of rice balls. I asked how far to the finish and was told 9.5 miles. I looked at my watch: 2:47. That still put us 22 minutes behind the 24-hour guidelines, but we’d made up 28 minutes in the last eleven miles, and I was feeling confident. “Think we can run 9.5 miles in two hours and 13 minutes?” I asked Megan, almost joking. I’d probably gotten a bit too confident, as that task turned out to be no joke.

We headed out along Quarry Road at a decidedly more relaxed pace. As expected, the technical uphill from the fire road to Highway 49 was slow, and we hiked most of it. We passed a runner and his pacer just before reaching the highway, then ran across and up the hill. This hill was slow, too, but was one of only two remaining climbs.

After cresting the hill, we ran through the meadow leading to Pointed Rocks (mile 94.3). I drank some ginger ale and tried to find a bag for pretzels: my stomach had been growling, and I wanted to eat something starchy to quiet it. We chatted with the volunteers: they said we had only 10k to go, and if we couldn’t run a 10k, we had no business being out here. I replied that we’d been running 10k’s all day. This probably took only a few minutes, but I regretted it when a volunteer said we had an hour and twelve minutes to break 24. An hour and twelve? I looked at my watch: 3:49. WTF??? For reasons I still don’t understand, I’d thought it was around 3:30. With only six miles to go, we were still 19 minutes behind 24-hour pace.

At the Memorial Day training camp, Megan and I attended a special screening of “A Race for the Soul,” a 2001 film about Western States. Several veterans of the film, including the ubiquitous Gordy Ainsleigh, showed up to talk about their experience and give advice. Gordy’s advice was simple: “Do the math.” That is, keep an eye on the clock. In 2001 he hadn’t and almost missed his goal.

I’d failed to follow Gordy’s advice, maybe because my GPS was off and I’d barely looked at my watch all day. I was doing the math now. With six miles left, 12-minute miles wouldn’t do it. 11-minute miles would, but we’d be cutting it close. I told Megan “We need to average 10-minute miles from here to the finish.”

What happened next was a win for adrenaline and the central governor theory. Frightened by the ticking clock, I took off as energetically as if I’d just started to run. I felt no fatigue or soreness, just a pressing need to make up time. Megan stopped to go to the bathroom and said she’d catch up. I said ok but wondered if she could. I hoped so, as I didn’t plan to wait.

The long, technical downhill to No Hands Bridge is a popular trail. I’d run it at least a dozen times before, in multiple training camps, Way Too Cools and Rio Del Lagos. I’d never run it this fast. I pounded down the hill, passing multiple runners as if they were standing still. They weren’t: they were probably going as fast as I would have been had I not been scared. Running this fast was scary, too: with so many roots and rocks in the trail, one misstep could lead to a broken ankle or worse — how much worse depending on how you landed after breaking the ankle. I couldn’t worry about that now. I’d have a long climb to Robie Point and beyond, and I’d be hiking that stretch, so I needed to exploit this downhill and the subsequent fire road to bank some fast miles.

I saw a light on the switchbacks above me and faintly heard Megan shout “I’m coming!” Good — at least she was on her way. I kept pushing down the hill, reached No Hands Bridge, and accelerated across. I had at least another mile of flat fire road before the hill, and I needed to make it count.

Shortly after reaching the fire road, I caught the couple we’d passed just before Highway 49. We’d left them behind after that crossing, but they hadn’t stopped at Pointed Rocks and pulled ahead. I berated myself again for dawdling there — I was still holding the bag of pretzels in my hand and hadn’t eaten one — but there was no point thinking about that now. I blew past them, wondering why they were walking: didn’t they know they could still break 24?

I looked back repeatedly but didn’t see Megan’s light. I started to worry she wouldn’t catch me. I was increasingly sure I’d break 24, but I wanted to run that lap around the track with Megan: she’d been with me this whole way and should be there at the end. Fortunately, I heard her voice just before reaching the hill, and she caught me on the hike up. Without a watch, I don’t know how fast I’d been going, but based on Megan’s data, I’d say I ran a few eight-minute miles. Not bad for 98 miles in.

We walked through Robie Point (mile 98.9) without stopping at 4:37. With only 1.3 miles to go, we were now three minutes ahead of the race’s 24-hour guidelines, having gained 22 minutes on that target pace in less than five miles. We were now safe, so we walked up the rest of the hill, then began jogging the last mile to Placer High.

The road was lined with lanterns, and I looked for the “WS 100” footprints painted on the road. I’m always happy to see these blue, red and yellow feet in the training runs, but especially so now. We jogged easily through the streets of Auburn and reached the track. I felt myself tearing up a bit: it had been a long journey, and I was ready but also not ready for it to end.

As we ran easily around the track, I heard Tropical John Medinger announce our finish, giving a shout-out to Megan, “my pacer in this race and in life.” I smiled as I approached the line but instinctively looked down, not given to public displays of emotion. And then it was done. We’d crossed the line in 23:52:21, making the cutoff by eight minutes. An emotional moment for me, captured on the livestream here.

I heard someone right in front of me say “Yuch!” It was Tod, Garret’s friend whom I’d met the day before. He’d finished only 33 seconds ahead of me, even though I hadn’t seen him all day. He’d run the first half an hour faster than me, and I’d spent the second half chasing him, catching up just at the end.

I chatted with Diana Fitzpatrick at the finish, thanking her for a great event. But we soon got cold and went in search of showers. We found them, but I hadn’t brought soap or a towel and had to make do with foaming hand soap from the sinks and paper towels. I took out my contacts, which had been burning my eyes for hours due to the dusty trails. Then we went back to Megan’s car and tried to sleep in the not-so-comfortable front seats. That didn’t really work, but it was good to close my eyes.

I opened them a few hours later to find that Dean had arrived. We headed to the post-race breakfast and talked about the race in the now-warm morning sun. We’d planned to watch the Golden Hour — the so-called best hour in ultrarunning — when the last finishers come in before the 30-hour cutoff. It didn’t disappoint. As the clock neared 30 hours, Tropical John called the names of the last runners to leave Robie Point with a fighting chance of making the cutoff. These runners had been out there nearly 30 hours, on the cutoff margin the entire time. The crowd cheered louder with every finisher, knowing time was running out. Seeing these runners digging so deep, and the crowd celebrating the last as much as the first, was a moving experience: this is what I love about our sport. The last finisher, Jennifer St. Amand, crossed the line with only 21 seconds to spare: a thin but surely gratifying margin after 30 hard hours on the trail. Here are the last few minutes, courtesy of Dean:

The drama didn’t quite end there. Less than two minutes later, Ash Bartholomew — the father of elite runner Lucy Bartholomew — entered the track. He’d missed the cutoff and wouldn’t be an official finisher, but he was still determined to cross the line on his own. He made a painful sight, doubled over with his hands on his knees, surrounded by friends ready to catch him if he fell. But he toughed it out, finishing and receiving as many cheers as any runner that day. Unbeknownst to us, the livestream had been covering him through drone footage: he’d been struggling through Auburn, hands on knees, for at least that last mile. You can watch it here from about 9:40 on. Here’s what we saw, which was enough:

After getting lunch, we went to the big tent for the awards ceremony. The mayor of Auburn spoke. The top finishers were celebrated. Courtney received a standing ovation for her astounding new course record of 15:29 — an improvement of one hour and eighteen minutes. The rest of us got our belt buckles, silver or bronze.

I’m not much into bling, but it’s a nice buckle. I heard on a podcast that they cost $430 each. I find that hard to believe, but they are made of Comstock silver and engraved on the back, so who knows? In any case, I’m glad to finally have one.

And that’s a wrap. Which brings us back to the question: What, if anything, is so special about Western States? Is it worth the hype?

I’m going to say yes. This was among my three best race experiences ever, along with the Vermont 100 in 2022 and the Bigfoot 73 in 2021. Not because my performance was so great: in fact, it was the worst finishing percentile (107th out of 377 starters) and worst Ultrasignup score (61 percent) I’d ever received. That’s to be expected when a fifth of the field are genuine elites and the rest are all seasoned runners, but still, for most of us, Western States is not an ego boost. Nor is it a spectacular course. While I have a soft spot for this area, most of the course objectively ranges from “okay” to “really nice.”

What makes Western States special is that everyone wants it to be. The runners who, knowing this may be their one shot, give it their all. The family and friends who crew, pace and cheer those runners to the finish. The 1500 volunteers — four for every runner — who mark the course, set up aid stations, and row runners across the river so the race goes off without a hitch. The thousands of spectators who cram the bleachers at Placer High to cheer the last runners in. The thousands more who watch the livestream from afar. (As soon as I finished, I received congratulatory messages from people as far-flung as Canada, France and Switzerland.) By collectively wanting this race to be special and showing up, they all make it so. So maybe it is a bit like that ice-cream store — if the store’s main draw was not the ice cream itself but the experience of standing in line and bonding with others who love ice cream as much as we do.

This December I’m back to the lottery, with one ticket. If I get in again, great. If not, that’s also fine. There are other races, and I’ve had my Western States experience. If you haven’t, you should too. As Gordy said at that film screening, when asked what we get out of this race, “You just have to do it. You’ll see.”

What a story! You continue to amaze me. Wow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Jon!

LikeLike

Well done Yuch! Glad you had the chance to run this iconic race, and with a sub-24 hr time. Thanks for the write up, cool how you got reenergized in the final stretches, well done!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Drew! Awesome experience, but already feels like a lifetime ago, especially since I’m leaving for Beaverhead tomorrow!

LikeLike

Wow back racing so soon – 100K?

LikeLike

Yep. Megan’s idea, as she still needs her WS qualifier. I don’t plan to push it too hard so soon after States…just hoping to enjoy the amazing views. 🙂

LikeLike

P.S. I was thinking that my Western States journey really began with that BRC movie night at your place, where we watched Unbreakable. 2013 or 2014, I think? Good times 🙂

LikeLike

Well done, bud! Just don’t get in the same year as me again next time so you can pace me, OK?

LikeLike

No promises, but the odds are against it 🙂

LikeLike