Tor des Geants, Take 3 (September 2025)

Note: This report, like all of my reports, is written mainly for me. I write these so I’ll be able to mentally recreate the experience in years to come. Which is to say: it’s long and filled with details you may find boring or superfluous. I.e., I won’t be offended if you just want to look at the pictures. 😊

My first Tor, in 2023, was a voyage of discovery. It remains my most fun and memorable Tor, even if I DNF-ed for reasons beyond my control. My second, in 2024, was a shitshow. I couldn’t sleep the night before; I struggled with the weather; but I did finish. This year I came back with one goal: to finally have a good race. That’s arguably not a great motive because, as any Tor veteran will tell you, this is not a race one can really control. A million X factors can make or break your race, and all you can do is prepare well and hope for the best. And, as Doug Mayer has noted, you shouldn’t get wedded to any particular notion of “best”: at some point, “Tor runners can only move forward if they let go of the ego-based distractions that have been powering them. External validation and self-esteem-powered goals no longer work. They need to let it all go. And just move.”

Well, whatever. I was going to try. As I saw it, my race would come down to three things: training, the weather, and sleep. The training I could control. The weather I couldn’t, but I could respond to it more effectively. I can’t control my sleep, either–believe me, I’ve tried–but that didn’t mean there was nothing I could do.

So here’s what I did before this year’s Tor:

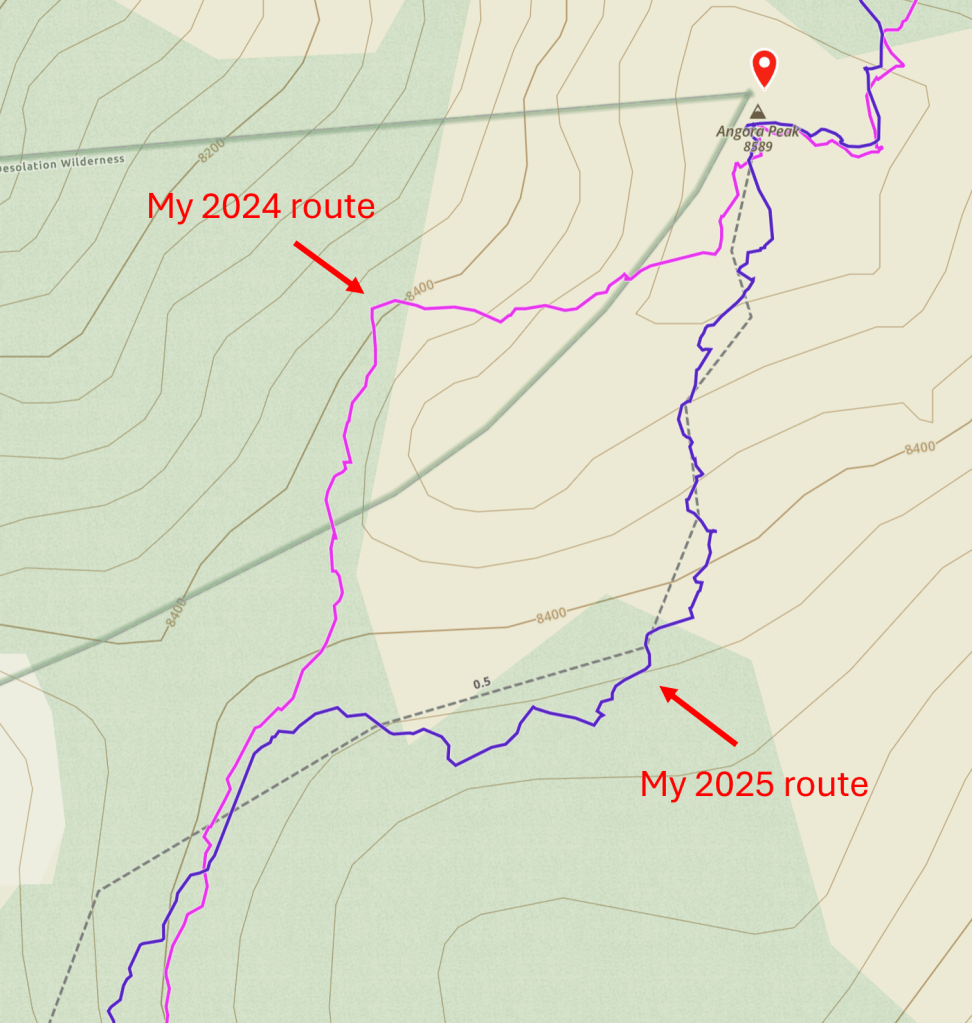

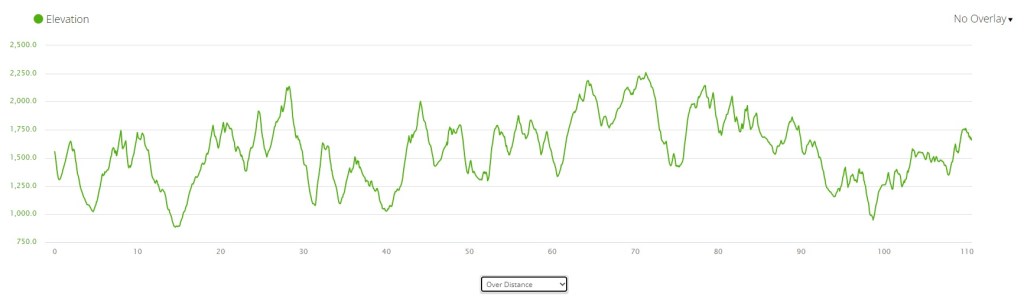

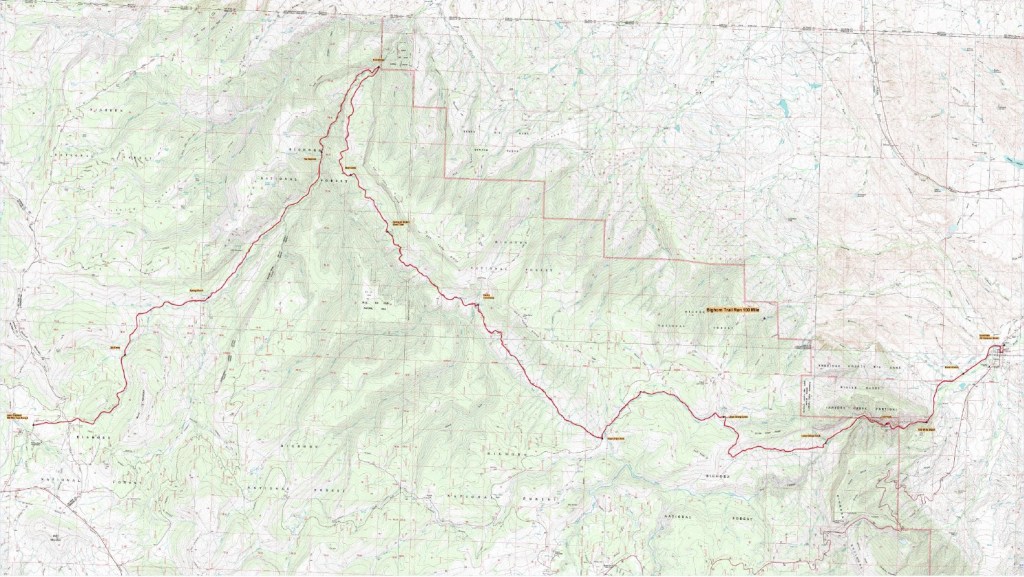

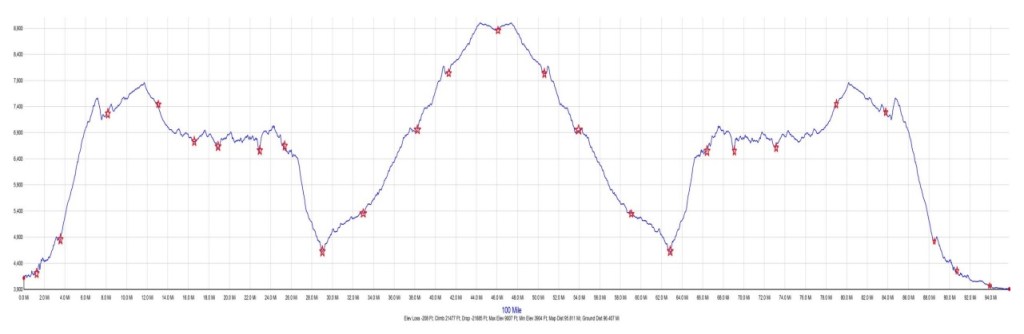

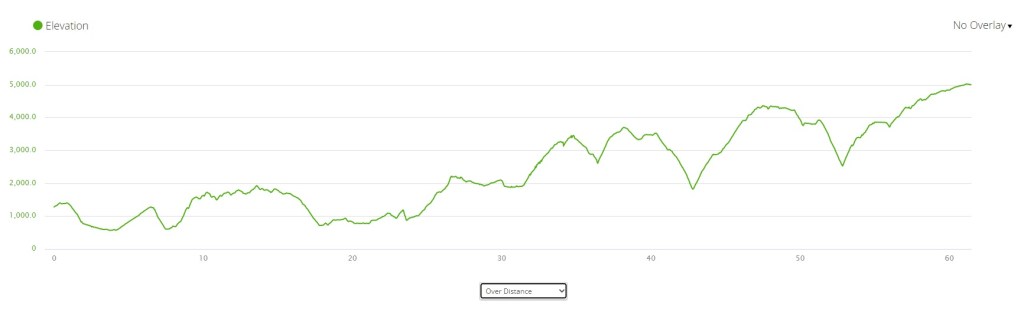

I trained well. I ran the Ouray 100M in July, a mountain race with a brutal amount of vert. After returning from Ouray, I did a series of regular 10k workouts: that is, ten thousand feet of climbing. There’s a hill in San Rafael that rises 425 feet in under a quarter-mile: I’d regularly do 24 repeats up and down this hill, for 10,000′ of climbing in ten miles. Megan and I also did a 10k workout on Mt Diablo and a couple on Mt Tam. By the time the Tor arrived, going up and down a 40 percent grade for hours was my natural state of being.

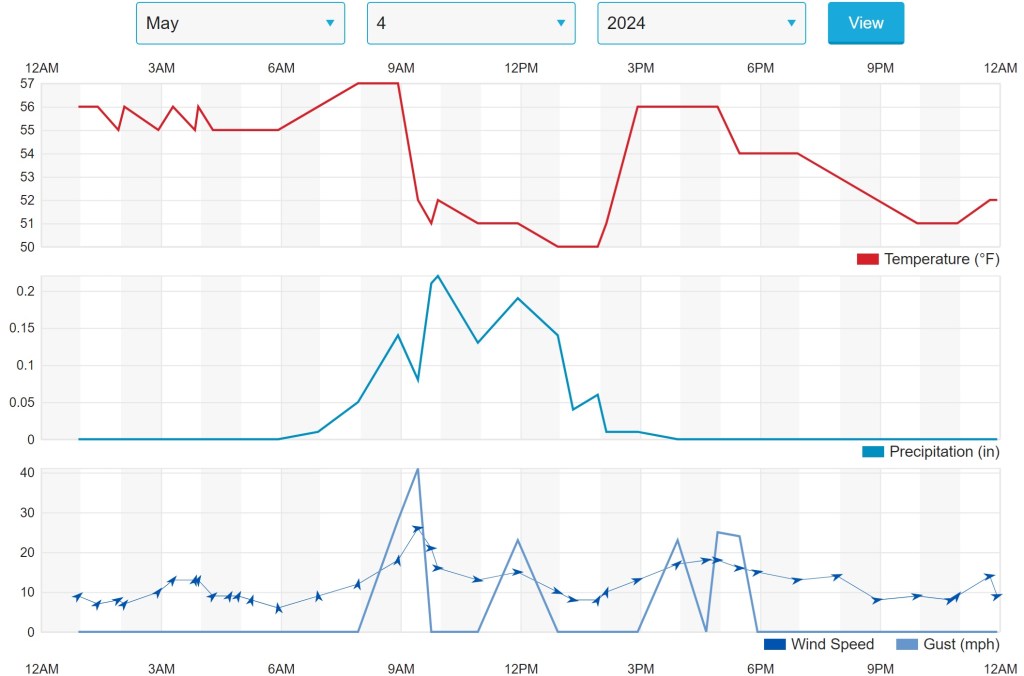

I bought some new cold-weather gear: a better pair of rain pants, heavier gloves, a warmer base layer, etc. I also bought a larger 15L hydration pack to carry all this gear. Last year I was spooked by the cold, rainy weather and put on my warm, waterproof layers at the first sign of high-altitude rain. In fairness, I’ve had some near-hypothermic experiences and have learned the hard way to take cold, wet weather seriously. But within a few minutes I’d be sweating buckets; the dreaded weather wouldn’t come; and I’d take all these layers off. Then I’d put them on again, take them off again, etc. etc. etc. This year I resolved to hold off on the warm clothes until I could no longer stand the cold, with the confidence that comes from having trustworthy gear.

Sleep has been my lifelong nemesis, and last year it derailed my race. I slept only an hour the night before the race and struggled to sleep during, and basically felt like a zombie the entire time. This was so disappointing that it led me to do something I should have done years ago: I finally tried cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI). The research is true; it helps, and I slept a lot better over the subsequent eight or nine months. I also phased out marijuana–which I’d been taking nightly for years–and caffeine. By the time the race arrived, I was caffeine-free–which would hopefully help me sleep the night before–and had reduced my marijuana tolerance dramatically, which would make the drug, when needed, more effective at knocking me out. (I planned on taking a large dose the night before.) I also planned to implement CBTI rules during the race: if I couldn’t fall asleep within 30 minutes, I’d get up, move on, and try again later.

All of which is to say: the Tor had been hanging over me for a while. I’d changed my life in ways small and large, from buying new gear to doing a lot of vert to finally taking my sleeping problems seriously. Most of these changes would be positive regardless of how this year’s Tor went. But, of course, I hoped they’d produce a good race.

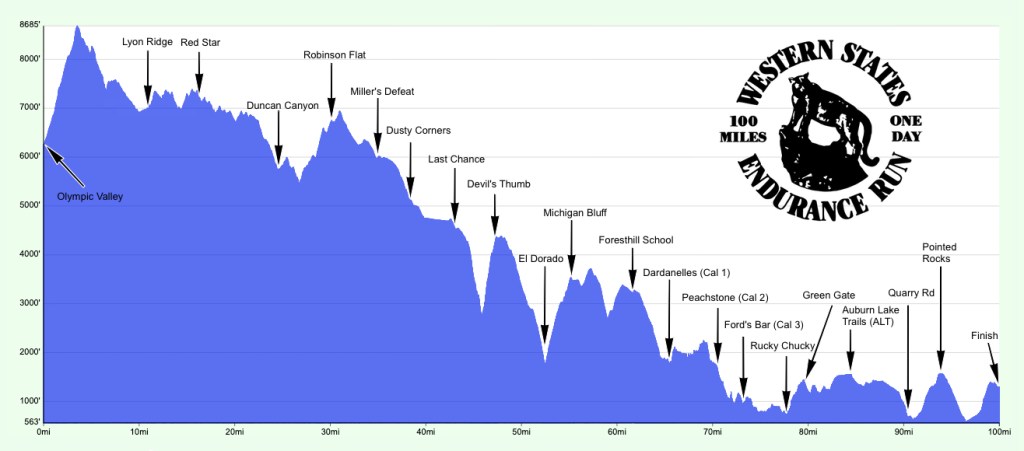

What would that mean? I set myself an “A” goal of sub-100 hours and a “B” goal of sub-110. Like most goals, these are somewhat arbitrary, but 100 is a nice round number and 110 means finishing before midnight Thursday–and hence sleeping that night rather than spending another on the trail. Also, my friend Garret had run sub-110 in 2022 and I hoped to beat his time. 😊 Either time would be a big improvement over last year, when Megan and I finished on Friday night in 131:47.

We arrived in Milan on Sunday, September 7, spent one night in Milan, then two nights each in Lake Garda and Verona. We arrived in Courmayeur on Friday, September 12, just in time to catch up with some friends and to see the start of the 450k Tor des Glaciers. Our friend Shane was running this year, and we wanted to see him off.

Saturday was the usual whirl of pre-race business: checking in, packing our follow bags, dropping the follow bags off, etc. The day flew by and felt busier than I’d have liked, but by 8pm we’d checked everything off and eaten a nice meal of homemade ribollita (which I’d also have for breakfast the next day). I took a tablet with 25mg of THC–a lot these days–and hoped for a good night’s sleep.

I guess the CBTI, caffeine deprivation and marijuana worked, because I slept a good seven hours that night. I was happy about this, and felt like the hardest part of my race was already done. Now it was just a matter of running. We dropped off our bags at the nearby Chalet Svizzero, which has a left luggage service, and made our way to the start.

The start was the usual crowded jog down Courmayeur’s Via Roma, followed by a wider paved road to the first ascent. While I love the energy of this start, I don’t love its trade-offs. I prefer to start my long races slowly, but a slow start here means a bottleneck at the first trailhead followed by a long conga line up the first pass. I aimed for a middle ground, fast enough to beat the main pack but slow enough to feel easy. I guess I accomplished this, although I still faced a long wait at the trailhead and a long queue of runners going up the hill.

It’s always a relief to crest Col ARP, as runners begin to spread out on the descent and the queue becomes less claustrophobic. I focused on making this descent smooth and easy, coasting down at a good clip with very little effort. I passed the Baite Youlaz aid station without stopping and continued on to the paved road, where I caught up with Mat, one of our Bay Area group.

All was going well until the final, steep, technical descent to La Thuile. I heard a runner behind me and did what I always do: stepped aside and let him pass. Then I noticed a long line of runners behind him and, without thinking, jumped back on the trail and ran fast enough to stay ahead. Several things are worth noting here. First, many European runners are much faster than I am on steep technical downhills. Trails like these are their bread and butter, and they’re somehow able to fly down them with little effort. Second, my ultrarunning prime directive is “run your own race”. Under no circumstances do I want my pace to be influenced by other runners, whose pace may not be optimal for me. Third, I now ignored my prime directive. Even as I ran–uncomfortably fast–down this hill, I was thinking to myself “This is stupid.” Why didn’t I just let them pass? Mostly, I was tired of conga lines and didn’t want to get stuck behind this one again. But while I can make sense of that decision, it was still a bad one, made without thinking, that would haunt the rest of my race.

I passed through La Thuile quickly, not even stopping to top up my flasks. I was light on water, carrying only two 500ml flasks and a filter just in case. But I hadn’t drunk much yet and thought I’d reach Rifugio Deffeyes soon. As it turned out, the 3,000′ climb to Rifugio Deffeyes took a while, and I was thirsty by the time I arrived. No harm done, though: I refilled and drank some extra for good measure, filled a ziploc bag with bread and cheese, and got back underway.

I was feeling good about things. I’d trained well; I’d slept well; the weather was great. I reminded myself that this was still going to be hard–the Tor is always hard–but right now I couldn’t ask for more.

The next col, Col de la Crosatie, has always been one of my favorites. It’s early enough that you’re still feeling fresh, and it has a rocky, technical summit with amazing views. I appreciated those views less this year, both because I’d seen them before and because it was rainy and cold. The wind picked up as we climbed, and many runners stopped to put on rain gear. I held off on mine, as I’d resolved to do: I knew it would warm up as we descended the other side, so I just had to tough out the next hour or so. And it was tough: by the time I reached the top, I could no longer feel my hands. But, as expected, the feeling returned by the time I reached Lago di Fondo on the descent.

After Col de la Crosatie, it’s all downhill to Planaval, then flat to the first lifebase at Valgrisenche. I hadn’t been paying much attention to my watch, as I had no benchmarks, but I knew I was ahead of last year’s pace. Last year I’d reached Valgrisenche around 9pm and had left by around 9:30. This year I arrived at 7:48, my first time getting there in daylight. I heard someone call my name as I rolled in: Maureen, here to crew Mat. I waved and continued to the lifebase.

I took my phone out of airplane mode for the first time and texted “Valgrisenche in” to our WhatsApp group. We had a good-sized group of runners and crew this year–me and Megan, Mat and Maureen, Jan, Colleen, Nate, Marie and Jesse, Mark and Sarah–and we’d formed a WhatsApp group to stay in touch. I ultimately never contributed much beyond “lifebase in” and “lifebase out”, but I appreciated the connection with the group. This was my first time doing the Tor alone, and that connection was all I had.

On my way in, I’d repeated my lifebase plan like a mantra: charge, eat, grab cold-weather gear, go. I only charged my watch here, as my phone was still at 97 percent, and grabbed some pasta to eat while sorting through my stuff. I didn’t love either the pasta–too chewy for a tired and time-conscious runner–or the sauce, but I forced it down. I stuffed my rain pants, down jacket, gloves, hat, light belt and batteries into my pack. At 8:20 I texted “Valgrisenche out” and left the lifebase, an hour and ten minutes ahead of last year.

Despite the earlier departure, it was dark when I left. This year’s Tor was a week later than usual, and the days were noticeably shorter. So I’d do the next two cols, as always, in the dark. I actually kind of welcomed the peace of the night–the endless, mindless step-after-step in the dark–but it would be nice to see what this section looks like someday. The first col, Col Fenêtre, felt relatively easy, as did the steep descent to Rhemes-Notre-Dame. Then came Entrelor.

Of all the Tor cols, I fear Entrelor the most. It’s always felt the hardest, although I can’t say that’s objectively true. Loson is the highest, and each is hard in its own way. But Entrelor is steep: from Rhemes-Notre-Dame, it rises 4,100′ in 3.9 miles. Like most of the cols, it gets steeper as you climb and is very steep at the top, with ropes and iron steps to assist you. But I think the real challenge is more psychological. Entrelor has several false summits, at least in the dark. You’ll see other runners’ lights high above you, and at some point they’ll disappear, suggesting the end of the climb. Then you’ll round a bend and see those lights keep going…and going. Because it’s dark, you have no views to stop and admire: it’s just you and the climb. Anyway, it’s hard for me. This year I found myself talking to the col: you know, “We meet again, Entrelor, my old nemesis; this time I’m ready for you” and other stuff like that. I also voiced something I felt, deep down, to be true: “This will be our last time.” This was all too hard; I couldn’t do it again. I just needed to beat Entrelor. One. Last. Time.

You can’t beat a col, of course: they don’t care about us. But Entrelor didn’t beat me, and I arrived at the summit in better shape than some. When I reached the rope and iron steps, a runner ahead of me was crying out, almost screaming. I wondered if he needed assistance, but he wasn’t having a medical emergency, nor was he in danger of falling. He was just really tired and making a lot of noise as he stumbled, haltingly, up the steps. What he needed to do was sit down for a while and rest. I felt mildly annoyed at this obstacle, picked my way around him, and moved on. Maybe this speaks badly of me, but like I said, he wasn’t in any real trouble–he just needed to take a break.

I arrived at Eaux Rousses at 3:49am, maybe three hours ahead of last year and 90 minutes ahead of 2023. Although I was making good time, my descent from Col Entrelor worried me. My legs felt terrible, and I was already having trouble running downhill. I thought back to that descent to La Thuile and wondered if it had already cost me my race. I resolved to take care of my legs going forward: better late than never, I guess, but it would have been better to think of this before, you know, trashing my legs.

I hadn’t planned to stay here long, but I felt wasted and needed some rest. I sat down on the one available bench and ate a bowl of orzo soup, then another. Feeling alone and dispirited, I checked the WhatsApp thread to see how everyone else was doing. Megan had left Valgrisenche at 9:28pm, a little over an hour behind me. I wondered where she was now: probably climbing Entrelor still. I missed her, but after two years of running the Tor together, we’d decided to see what we could do on our own.

I hauled myself off the bench and into the cold early morning. Several others left with me, but I dropped them quickly: I needed to warm up and wanted to be alone, so I hastened up the long, gradual ascent to Col Loson. After a mile or so I caught up with another American runner, Ely. Like me, he was doing this race with his wife, an elite runner who would ultimately place fifth. He mentioned that he’d met Mat earlier in the race, and also that he’d met my friend Jack during the 2022 Tor. Small world.

We eventually drifted apart, and I continued toward the col. The valley leading to Col Loson is one of the most breathtaking parts of the course, and I was disappointed to be doing it in the dark: it didn’t get light until I was well up the col. I was on the western side, so the sunrise hit the mountains to my west long before it hit me. The views were lovely, but I was relieved to finally reach the summit and feel the sun’s warmth.

Shortly into the descent, I reached the small trailside table that–at least for the last three years–has always been there serving water and Pepsi. It’s not an official refreshment point, which makes it all the more welcome. I chugged a couple cups of Pepsi and, while doing so, heard someone call my name: Ely. We continued down the steep hill together, but he was moving better than I was, as I’d lost my downhill legs. I needed to make a pit stop anyway, so when we reached the plateau below I let him go as I searched for a rock to hide behind. As I did my business, I watched a long column of runners pass by.

The descent to Cogne is long and technical, and I was dreading it on my current legs. It’s not that I couldn’t do it, but I knew it would be slow and unpleasant. I stopped at Rifugio Vittorio Sella and ate several pre-packaged fruit pastries, hoping the sugar would restore me. It didn’t, and I continued slowly down the trail. A lot of runners passed me, while I passed none.

I eventually reached the flat paved road to Cogne and learned that I could still run, just not downhill. That was something: in previous years I’d walked those last two miles. I maintained a slow jog all the way to the lifebase and at 10:26am texted “Cogne in” to the group.

To my surprise, Shane was there. I’d hoped our paths would cross–the Geants and Glaciers courses share many miles–but I didn’t expect it to happen this soon. He’d decided to drop here, after 160k: he wasn’t having fun and wanted to enjoy the rest of his time in Italy. Fair enough. At some point we all ask “What am I doing here?” It’s a very personal question, and we all have to answer for ourselves.

I was glad to see a familiar face, and Shane kindly brought me food and refilled my flasks while I sorted out my gear. My pack was way too full of warm things I hadn’t used, even in the cold of Col Loson. The stretch to Donnas would be lower and warmer, especially since I’d probably leave the high country before nightfall. Rain jacket, base layer, hat and gloves, bivvy sack: in. Down jacket, rain pants, emergency blanket: out.

I told Shane about my downhill problems. He assured me I was doing great, but unfortunately kind words don’t fix bad legs. I ate three or four yogurts and a bowl of pasta, hoping the food and rest would work some magic. Ely, who’d arrived before me, came over and said hi. A runner sitting next to Shane had a coughing fit that went on and on. This “Tor cough” is common and generally doesn’t mean the person is sick: I had a mild case myself. Still, I don’t love being coughed at and don’t think it’s that hard to cover one’s mouth.

Neither the food nor the rest worked any magic, but it was past time to go. At 11:22 I texted “Cogne out” and made my way through the village center. I chided myself for taking so long: I shouldn’t have needed an hour to eat and discard a few things.

Despite my fatigue, I looked forward to the next section. It’s probably the easiest leg of the course, with no serious climbs and a long and mostly gradual downhill to Donnas. The scenery is gentler too: due to the low elevation, it’s less jagged peaks and more grassy foothills. I had fond memories of doing this stretch with Megan in 2023, when we saw it for the first time.

Repeat performances are always different, and this year I chugged purposefully along the trail without noticing the landscape so much. That was true of most of the course, and one reason I didn’t think I’d do this again. Still, the miles went by quickly, and by mid-afternoon I reached this section’s high point, Finestra Di Champorcher. I took a moment to admire the view, then headed down the steep and technical descent.

The descent immediately reminded me that my legs were not all right. People began to pass me again. I felt frustrated and stupid for doing this to myself. Eventually, however, we left the technical part and hit the more gradual fire road. On runnable downhills, I’m pretty good at relaxing my legs and letting gravity pull me down. I can only do this, however, when I’m not worried about going too fast and losing control. This was a big constraint now, since it was the muscles that maintain control–the braking and stabilizing ones–that were shot. As a consequence, my current definition of “runnable” was pretty narrow: non-technical, with less than a five percent grade. This fire road approximated those conditions, so I thought I’d see what I could do. My legs initially resisted the attempt to let go, but I forced them to and was soon running fast with little effort. I passed all the people who’d recently left me behind, many of whom were walking. I thought about how different runners were: how could those who’d danced so quickly down the technical descent now let this runnable hill go to waste? Didn’t they know that this was where one could move fast?

It didn’t take long to reach Rifugio Dondena. In 2023 we’d arrived here around 9pm and slept for the first time. It was now 4pm, and while I was very tired–I’d been going 30 hours–I was loath to sleep while the sun was still high. So I took another caffeine pill and resolved to make it to Donnas before lying down. I ate a bowl of pasta on the outdoor patio, enviously watching some other runners order beers. I’d have liked one myself but didn’t think that would help me reach Donnas.

Donnas is the lowest point on the course, and I could see its valley ahead, filled with fog. The descent from Dondena was initially grassy and gentle but got steeper and more technical as it entered the woods. People began to pass me again. I felt embarrassed to be moving so slowly, but every long step down was painful–and it was all long steps down. I thought back to 2023, and how Megan, Shane and I flew down this stretch. I now wondered how that was possible, but a lot of things feel different on good legs.

It was here that I began to notice that my memory of the course was not just incomplete but also biased. I seemed to remember parts I liked while forgetting parts I didn’t (with Col Entrelor a notable exception). In my mind, the whole stretch from Dondena to Donnas was runnable and fast, when in fact much of it was…like this. It’s true that I’d run this stretch faster in previous years, and parts of it are runnable and fast. But the fact that I remembered only those parts while somehow blocking out the technical stuff warrants some thought. I suspect that I construct narratives about different Tor sections–good, bad, easy, hard–and unconsciously bring the details into line. Which is to say that my memory is human.

Good, bad, easy or hard, I eventually reached the Chardonney-Champorcher aid station. Ely caught up with me here: he’d left Cogne after me but was moving faster. I left ahead of him, but he soon caught up again and passed me by. I didn’t expect to see him again. But a short while later, he and an Italian woman descended a hill toward the trail, having apparently gotten off course. They weren’t sure I was on course, either, but the GPX checked out, and a few meters later we saw a flag.

We didn’t exactly run together to the next aid station at Pontboset, but we arrived at the same time. He’d pull ahead on the steeper downhills, and I’d pass him again on more runnable ones. This was my first time reaching Pontboset in daylight, so I was able to see several of its beautiful namesake bridges. I left the village before Ely, heading down to and across the Fiume Ayasse, up the steep hill on the other side, then down again toward Bard. He caught me on the final steep descent and quickly left me behind.

I reached Bard just before dark, glad to see its towering fortress lit up and to take the long, cobbled street through the ancient village. This place was no longer novel or mysterious to me, but still one of my favorite parts of the course. After so much time in the mountains, Roman and medieval architecture are a lot more engaging than more rocks.

The paved road to Donnas is long, and I got there well after dark. I paused at a cafe just before the lifebase, wondering if I should buy a beer. I wasn’t sure if they’d have any at the lifebase–they do at some but not all–and I thought it might help me sleep. But I felt too weird about going in in my current state and continued on. I reached the lifebase at 9:00pm Tuesday, exactly 35 hours after leaving Courmayeur.

Ely was already here, and I chatted with him while I ate. They had a couple of good salads: a veggie salad made from grated carrots, apples and cheese and a fruit salad with apples, bananas, nectarines and grapes. I ate a lot of both as well as four boiled eggs. I scanned the WhatsApp conversation and saw that Megan had been at Dondena at 7pm, three hours after me. I then noticed she’d texted me directly, saying she was aiming to reach Donnas by 2am. I responded “I’m going to give myself 3 hours to sleep. Legs are really messed up.” I’d probably still be gone by the time she arrived, but there was a chance we’d overlap.

I realized I couldn’t talk, text, eat and organize my gear all at the same time, so once I finished eating, I gave up on the gear and decided to sleep. I’d finish all that when I woke up. I grabbed my follow bag and pack and headed up to the sleeping area.

I’d tried to sleep here last year and never wanted to try again, as it was hot, noisy and crowded. But the timing dictated that I try again now. I figured the room would at least be cooler at night, and maybe also less crowded since I was further ahead in the pack. Neither was true. It looked like everyone in my part of the pack had decided to spend the night here, and there were only a few free cots. And my god, was it hot: probably 90 degrees. Why didn’t someone open a window? Does anyone think this feels good?

The heat dismayed me, since I have a hard time sleeping when it’s warm (my ideal is <60 degrees). But I wasn’t in any state to continue, so I picked a cot and settled in. I felt really gross, having been trekking for 35 hours in warm weather, and smelled awful. I didn’t have the time or energy to take a shower, but I did put on a clean set of running clothes from my follow bag. I inserted my dental night guard, put on my sleep mask, and did what I could to drown out the incessant coughing around me: earplugs and headphones with brown noise. I set my alarm for 1:15am, which gave me a little over three hours to sleep. That’s a lot of time, but I knew I was unlikely to sleep for all of it and hoped for maybe two hours.

The heat was uncomfortable, and I could feel sweat streaming down my forehead as I lay there. But I was tired enough to eventually fall asleep, and I’d guess I got my two hours. I woke up the instant my alarm started to chime, but it took me a few minutes to shake off the fog, gather up my gear, and head back down to the main hall. There I got everything in order, which took longer than it sounds. I was moving slowly and didn’t especially care. Once everything was ready to go, I made a last trip to the bathroom.

When I got back, I looked at my text messages for the first time since getting up. I noticed that Megan had texted me at 1:39am: “I’m here”; “I’m gonna take a shower”; “Ok I’m done with all my stuff. Heading to bed”. Somehow I’d missed both those texts and her. I went up to the sleeping area, found her cot, and whispered hi. She was awake enough to grab my hand but was trying to sleep, so I left her in peace.

I guess I wasn’t quite ready to go, because a few minutes later I saw Megan in the main hall. She’d been unable to fall asleep and was going to get a massage. I felt for her: it’s terrible to be so tired yet unable to sleep. She was also worried that she might be getting sick. I wished I could stick around and catch up with her, but I’d already been here way too long, so I gave her a hug and headed out at 2:15am. Five hours and fifteen minutes is a long stay for two hours of sleep. But last year I was here even longer and didn’t sleep at all, so I called it a win.

However much I had or hadn’t slept, I felt a whole lot better leaving Donnas than I had going in. It’s amazing what even a little sleep will do. I was in good spirits as I passed through Donnas and into Pont-Saint-Martin, seeing the old Roman bridge at night for the first time. My legs felt dead as I started up the first stairs into the hills, but I knew they’d feel better after the initial shock.

I also felt happy to be alone. I saw no lights behind or ahead, and the peace and quiet was a welcome change from the crowded early stages of the race. Having other runners around makes me feel like I’m in a race, whereas solitude makes it feel like a hike. I much prefer the latter feeling. I passed the stone pool above Perloz where Jan’s son Lucas liked to cool off during the Tor. It didn’t call to me now, but I’m sure it’s more inviting by day.

Perloz is arguably the Tor’s prettiest aid station, set in a picturesque village high above the Lys Valley. It also has some of the best fare: donut-like pastries and fresh-squeezed orange juice made on-site. I stopped long enough to drink several cups of the latter, then headed down to and across the River Lys.

I’d been looking forward to the next few miles. There would be some climbing, but there’d also be a long, flat runnable stretch where I could make up some time. I’d caught up to other runners and was now passing them regularly, taking it as a good sign that none were passing me. My downhill legs still weren’t great, but I was moving well uphill. I reached the long flat stretch and ran the entire thing. Then I hit the steps.

The climb from Donnas is unique in that much of it is not in the wild but on stone steps that wind past homes and farms. Even at night, someone might step out of their house and shout “Bravo!” This doesn’t make the climb any less long or steep, but somehow its manicured and civilized nature makes it feel easier to me. I hasten to add that not everyone shares my feelings.

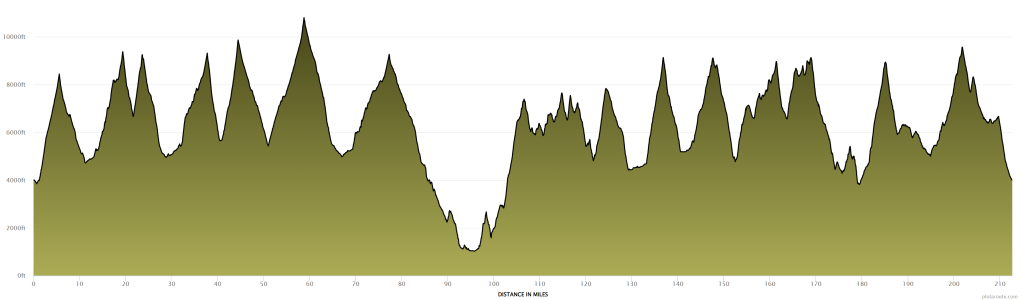

Eventually the steps end, but the climb keeps going. And going. The stretch from Donnas to Gressony is widely considered the Tor’s hardest leg, and the numbers support this, with almost 20,000′ of elevation gain in 54k. By the time the sky got light, I was sick of climbing and ready for Rifugio Coda. For the past two years, Coda had had amazing food options, like pizza and veggie quiche. I didn’t think I’d been fueling well and needed something like that now.

The trek to Coda reminded me again how biased my memory was. I’d thought my hard work was done when I reached the ridge, but in fact the ridge itself involved a lot more climbing. I was going to have to work for that pizza and quiche. Fortunately, the sunrise views were uplifting and got me the rest of the way.

I’d made good time to Coda and was ready to rest and eat. Sadly, there was no pizza or quiche–just more pasta soup. It was, at least, better than the usual orzo stuff: a different kind of pasta and better broth. I ate two bowls.

My next stop would be Rifugio Barma. I had fond memories of Barma as well, of how I enjoyed their polenta that first year with Megan. I also remembered the journey there as moderate: gentle rolling along a ridge. The latter memory was, once again, rosier than the actual trail. I knew there was a steep, very rocky descent right after Coda, but I’d forgotten how long it goes on. And while the trail that follows is “rolling” in the sense that it goes up and down, both the ups and downs are long, steep and technical. It’s not an easy stretch.

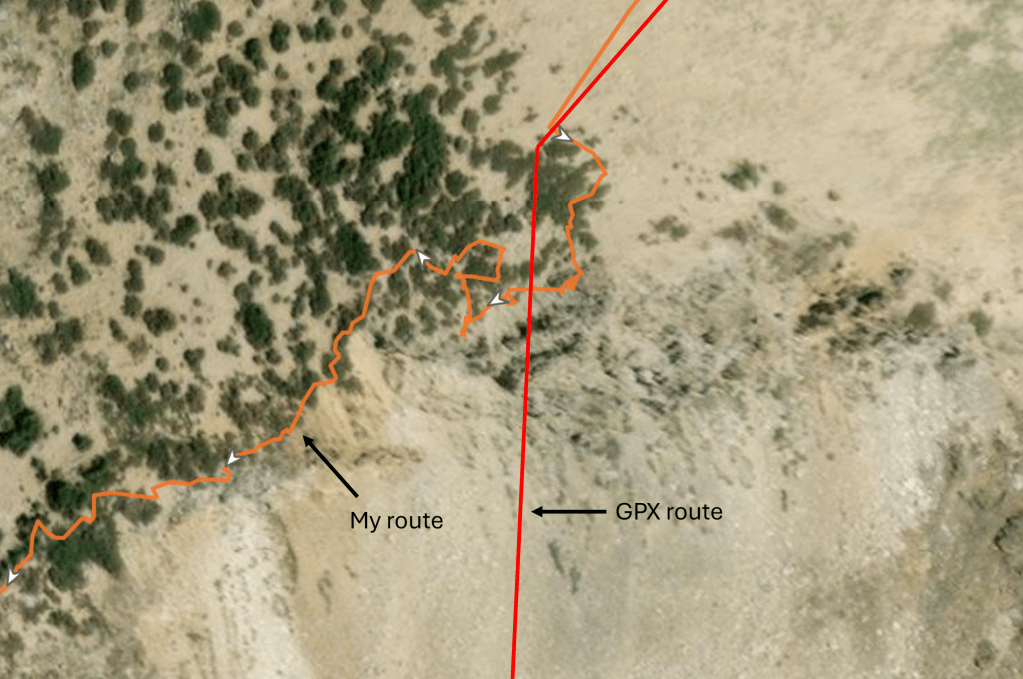

Shortly before Barma, just after passing what I call “The Mansion”–a grand but long-abandoned stone house–I got a bit confused. The flags indicated a right turn off the main trail, and though I followed them, something felt off. I wasn’t sure we’d gone this way in previous years, and the flags were marked with silver tape, the color of Tor des Glaciers. I remembered how, two years ago, a Glaciers runner got off course around here, not realizing the two courses had diverged. I stopped and checked my GPX: it clearly showed that I’d gone off course and shouldn’t have taken that right turn. I returned to the junction and encountered a French runner, Quentin, who felt sure we should follow the flags. I hesitated a minute, then followed him. He told me he’d already encountered several discrepancies between the course markings and the GPX. This seemed to be another, and I’d find others later in the race. No harm done, at least for me, but this seems like something they might want to fix.

I reached Barma at 10:58am and asked for a bowl of polenta. Not as good as I’d remembered–it could have used more sauce–but still a nice change from pasta soup. I’d have liked a second bowl, but the clock was ticking, so before 11:30 I got underway.

One interesting aspect of the Donnas-to-Gressonay stretch is that, while it’s very hard, it has no real “crux”–no particularly brutal climb or punishing descent. It’s just relentless up and down. After Barma there’s a relatively easy climb to Col du Marmontana, then a steep but short descent to Lago Chiaro (which I remember as the place where Megan got her knee taped in 2023), then another moderate climb to Crenna di Ley, and so on. Don’t get me wrong: it’s all hard, and the cumulative effort takes a toll. But there’s no place in particular that sears my memory like the climb up Col Entrelor or the long descent to Oyace.

That said, the last mile or so to Colle Della Vecchia is pretty awful. Or at least felt so to me. It has no big climbs or descents, but my legs hated the steady, technical up-and-down. By the time I reached Colle Della Vecchia, I was ready for a break and asked for polenta with tomato sauce. This usually gets me…tomato sauce, but after a few bites I realized the sauce contained bits of meat, maybe ham or pork. I was too tired and maybe too sheepish to ask if they had anything else, so I decided to just eat around it. An Italian runner watched me curiously as I spit out the meat, asking if I didn’t like it. “Sono vegetariano” I replied.

The final descent to Niel begins with a level stretch lined with flat rocks–almost like paving stones–that I enjoyed. This was my first time seeing this section by day, and I enjoyed the views too. Soon, however, the descent began for real, and I did not enjoy that. It was steep and technical and painful, and runners started passing me again.

I stopped in Niel just long enough to eat a bowl of their signature polenta and check the WhatsApp thread. Megan had left Donnas, although I couldn’t tell when. Colleen had reached Donnas. Nate had become nauseous and had to drop out. No news from Mark or Mat, but hopefully that was good news. I texted the only news I thought worth sharing: there was polenta at Barma, Colle Della Vecchia and Niel, and Niel’s was the best.

The climb from Niel to Colle Lazoney didn’t take long, and I soon began the long descent to Gressoney. This descent has two distinct parts. There’s an upper part that has smooth-ish trails and beautiful views of the valley ahead. I like this part, and it flew by. Then there’s a lower part that’s in the woods, has no views, and is super rocky and technical. I don’t like this part, and it went on forever. I took some comfort in seeing that my immediate peer group wasn’t moving any faster than me: everyone’s legs were tired now. I also took comfort in their relatively low bib numbers. Tor numbers are based on ITRA scores, and while the vagaries of those scores produce a lot of anomalies–really strong runners with high numbers and vice-versa–on average, faster runners have lower numbers. Most of the numbers I saw were still in the double and low triple digits, which I took as a good sign.

I reached Gressoney at 8:51pm and forced down a few bowls of food: vegetable soup, more fruit salad and boiled eggs. I checked the WhatsApp thread while I ate. Megan had reached Niel, four hours and fifteen minutes behind me. She wasn’t sick, fortunately, and was planning to nap there. Jan was in Gressoney and asked if I needed anything. I told her no thanks; I wanted to sleep ASAP.

I’d been looking forward to sleeping here, as I remembered it as one of the better places: cool and quiet, with big comfy mats. I was right about the coolness and the mats, but this year wasn’t so quiet. Every few minutes someone would open a door with squeaky hinges, and I’d hear a really loud “CREEEEAAK!” I lay there for a while failing to nod off. I thought about my plan to follow CBTI rules: if you don’t fall asleep in 30 minutes, get up and try again later. I actually felt awake enough to do that, but the long descent to Gressoney had trashed my legs, and I didn’t think they could go on without more rest. So I continued to lie there awake.

I must have fallen asleep at some point, because I woke up to my alarm at 12:45. I’d been lying there for three hours but probably slept, at most, an hour and a half. Better than nothing. I felt very groggy, and it took me a while to collect myself and get ready to go. It was 1:35am by the time I texted “Gressoney out”.

It’s dismaying to come off these five-hour stops and see how much your average pace has slowed. When I’d entered the lifebase, I was still hovering around 2.5mph. Now I was closer to 2, and that wouldn’t be my last sleep. My A goal was now out of reach, but I still held out hope for the B. I jogged out of Gressoney in an effort to make up time, but maybe haste does make waste, since I somehow missed a turn. It didn’t take me long to get back on course, but then I realized I’d dropped a glove while checking my GPX and had to go back to retrieve it. The whole mishap didn’t cost me more than five minutes, but it was frustrating to do so much jogging and still be behind the walkers I’d passed ten minutes before.

I’ve heard that most people who reach Gressoney go on to finish the race. That makes sense: many runners who were going to drop have dropped by then, and the remaining ones begin to see the end of the tunnel. But also, the course seems easier from here. I say “seems” because I can’t find objective evidence that this is true. By Gressoney you’ve done 60 percent of the distance and 60 percent of the elevation gain, so the vert-per-mile doesn’t change. Perhaps the terrain changes in other relevant ways, but I don’t know how to quantify this. It’s possible that 40 percent is simply less than 60.

Be that as it may, the climb from Gressoney to Col Pinter doesn’t seem bad. It’s a lot of climbing, but it never seems crazy steep. The landscape is different from the earlier cols, too: bare granite crags are replaced by green, grassy hillsides. I couldn’t see any of this now, and wished I could. Last year I’d been struck by the beauty of this stretch but didn’t take any pictures due to the rain and cold. I’d hoped to make up for that this year, but it wasn’t to be.

Leaving Gressoney felt very different from leaving Donnas not only because of the terrain but also because I wasn’t alone. I was always just behind or ahead of someone, which I found frustrating. I particularly dislike having people right on my tail because I always feel psychological pressure to speed up. (Which can lead, e.g., to running too fast downhill and trashing your legs.) I’d step aside to let people by, but soon someone would be behind me again. I saw a string of lights up ahead and thought about how runners “clumped” into groups–which you wouldn’t expect if everyone was going their own pace. I also noticed that even runners who caught up to me–and were therefore going faster–would often match my pace once they’d caught up, even if there was plenty of room to pass. It dawned on me that many Tor runners like to be with others and stick with them when they get a chance. Well, to each their own. I wanted to be alone, so I eventually stopped and waited until everyone near me was far ahead. Then I moved forward again, glad to have the night to myself.

I was also glad to crest Col Pinter and head down the other side. The early part of the descent is quite steep and technical: so technical that I didn’t mind it, since no one could run here anyway. After that, there’s a gradual runnable part that I also liked. But the last couple of miles were the steep-and-rocky-but-runnable-on-good-legs combination that I’d come to hate. I felt miserable by the time I arrived in Champorcher.

I hadn’t planned to stay long in Champorcher, but after a bowl of orzo soup and a cup of sweetened tea, I had another bowl and another cup, and then another. I was recharging my batteries, I told myself, but mostly I was just tired. There’s a point in every long race where things start to look bleak, and I was at that point. My legs felt awful; I was falling asleep on my feet; I’d reached my own “What am I doing here?” moment. I texted to the group: “This feels like the point in the race where you start to have serious doubts about all of this.” But doubts wouldn’t get me back to Courmayeur, so after some more tea and bread and cheese I forced myself back outdoors.

It had been dark when I entered the aid station, but it was light now, and I could see snow-capped peaks ahead. The brightness of the morning lifted my spirits a bit. Last year I’d done the whole next stretch to Valtournenche in the dark, so I was looking forward to seeing it for the first time.

The climb to Rifugio Gran Tournalin was beautiful and not too hard. A lot more fun on a clear, sunny day than in last year’s howling wind and rain. I stopped briefly at the rifugio for some coffee, bread and cheese, then continued on to Col de Nannaz.

From Rifugio Gran Tournalin, the remaining climb to Col de Nannaz is short and easy. The trail was crowded here, not just with Tor runners but also with backpackers. As I approached the summit, I decided to go off trail for a bathroom stop. Not all Tor runners have great trail etiquette, and it’s dismaying to see how much poop and toilet paper they leave along the trail. I didn’t want to be part of that problem, so I clambered over the talus to hide behind a large boulder fifty or so feet off trail. The boulder hid me from view from below and behind–but not, as I learned, from above. While doing my business, I noticed that the backpacking group I’d recently passed had turned around at the summit to admire the landscape they’d just left behind. I’m not sure if they saw me, but I’m pretty sure I photobombed some of their pics. Hopefully they’ll laugh when they notice.

The next few miles were pretty easy: a rolling ridgeline to Col des Fontaines followed by a mostly gradual descent. I recalled enjoying this stretch at night and liked it even more by day.

The bliss didn’t last: the last couple of miles to Valtournenche are awful. Once you enter the woods–it’s always when you enter the woods–the trail becomes a steep, rocky quad-killer. I was mentally prepared for this, having done it before, but it still hurt like hell and seemed to go on forever. By the time I reached Valtournenche, I felt wasted once again.

I’d hoped to sleep at Valtournenche, as I’d slept well there last year and remembered it as a good place. I also didn’t think I’d have great sleeping options for quite a few miles to come. However, I arrived at 12:33pm and didn’t want to waste the daylight hours, so I resolved to just eat something and move on. My stomach wasn’t doing great, so I ate six containers of yogurt. A runner named Victor, who I’d been going back and forth with since Gressoney, offered me some chocolate protein powder, which I gratefully accepted. I didn’t know it until I saw my post-race pics, but he and I had been running together since the start:

Although it was warm, I decided to pack most of my cold-weather gear for the upcoming section. I’d be on an exposed ridge much of the night, and I thought it might get windy and cold. My hands had gotten numb, even with my light gloves, on Col Loson, so I decided to bring my heavy gloves now. They were so bulky that I couldn’t fit them in my pack and had to strap them outside. I felt kind of silly leaving in the warm afternoon with the heavy Gore-Tex gloves on full display.

I tried to move quickly, hoping to get as far as possible before dark. I remembered the next section as very beautiful and wanted to see as much of it as I could. The initial climb out of Valtournenche is unremarkable–another hike through the woods–but once the trail opens up, there are miles of stunning views.

I stopped only briefly at Rifugio Barmasse and Bivacco Vareton for water and snacks. The stretch between Vareton and Fenetre Du Tsan is one of my favorites, but I was having trouble enjoying it now. One runner seemed determined to shadow me, and no matter what I did, he always seemed to stay on my heels. I’d speed up, and he’d speed up with me. I’d slow down, and he’d do the same. I’d stop to take a picture, and he’d wait patiently behind. I don’t want to sound like a crank, but when you’re stopping frequently to take pictures, you don’t want to worry about your shadow running into you. I’d step aside and motion for him to pass, but he’d signal his wish to stay behind. Some people like to follow, I guess.

The trail got more crowded as I approached Fenetre Du Tsan. I noticed that not all the runners were from Tor des Geants: some were doing the 130k Tot Dret. That race had begun from Gressoney about five hours before I’d left, and I was now catching part of the pack. We pushed our way up the final climb and were rewarded with the view through Fenetre Du Tsan.

The descent from Fenetre Du Tsan to Rifugio Lo Magia is steep, long and rocky, and I was feeling demoralized long before I got to its end. In the flattish last mile or so, I met an American named Tom who was also doing this for the third time. (Coincidentally, he was also in that picture with me and Victor from the start in Courmayeur.) We chatted until we got to Rifugio Lo Magia, where we both hoped to sleep a bit. It was getting dark, and I didn’t think I could go much further without some real rest.

I was happy to learn that Lo Magia had beds, which I wasn’t expecting. After two bowls of soup, I requested a bed for two hours. Unfortunately, it didn’t work out that way. It was already around 7:15pm when the person in charge wrote down 9:00pm as my end time. Then I had to use the bathroom; then someone had to show me to the room; then it turned out the bed had no blanket or pillow, so I had to go in search of them (securing a blanket but not a pillow). It was around 7:40 by the time I actually lay down, and sleep didn’t come easy after that. It was super hot in the small room with four occupied bunk beds, and my legs were very sore. I eventually drifted off despite the heat and the pain, but I doubt I got more than 30 minutes of real sleep. It took me a while to pull myself together, but eventually I made my way downstairs, drank another cup of tea, and headed out into the night.

Although I hadn’t slept well, I still felt a lot better leaving than arriving. My departure was timed well, too: I saw no one ahead or behind; just a dark, peaceful night. It felt very cold when I left the rifugio, but I heated up quickly on the climb and stopped a couple of times to shed clothes. After a steep climb through the woods, I broke through to the open ridge above.

There was no moon to speak of, so I could make out the topography only through distant headlamps: some far above me and others far behind, still making the descent to Lo Magia. Despite the darkness, it was beautiful, and the sky was full of stars. But, oddly, no Milky Way. On a clear night in the Sierras or Rockies, the Milky Way dominates the sky, but I saw no trace of it here. I didn’t understand why: the air was thin, the sky was clear, and there was no light pollution. But for whatever reason, the sky here was just blackness punctuated by individual stars.

I stopped at Rifugio Cuney long enough to eat two bowls of pasta, and at Bivacco Clermont for two cups of tea and some cookies. Otherwise I just kept going along the ridge, trying to be mindful of the occasional vertiginous drops to one side. Last year this section offered spectacular views: mountains as far as the eye could see. This year it was just me and the trail ten feet ahead.

I reached Col de Vessonaz, a big milestone in my mind. Here began a 10k descent to Oyace: insanely steep at first, then less steep but more technical for miles after that. I remembered enjoying it with Megan last year, but given the current state of my legs, I thought this year would be less fun. Still, the wind was howling on the col, so without pausing I headed down.

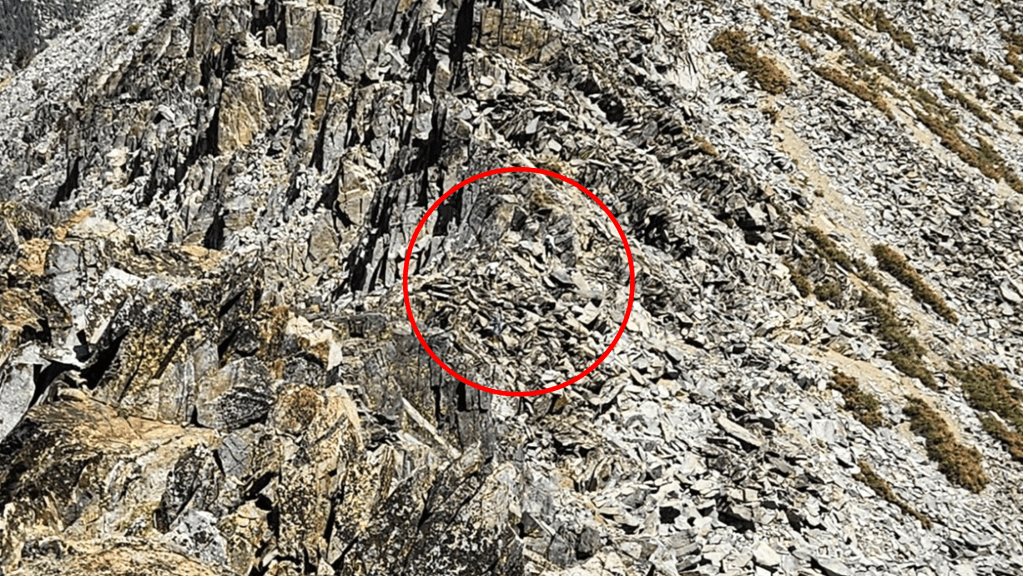

The first few hundred meters are both smooth and crazy steep. I doubt I could descend it without poles without losing control, and you can see several spots where someone did just that, sliding off the switchbacks and leaving a track through the scree. This doesn’t last long, however: soon it becomes a more gradual but rockier descent. One that goes on and f***ing on.

This was the hardest part of my race. Every step downhill hurt, but the physical pain bothered me less than the contrast with last year. Megan and I had not only made good time but also had a blast, running fast and sometime laughing uncontrollably–we were a little punchy by then. This year I was crawling, and every slow step was hard. Even worse, the lead runners from the Tor 100k (“Cervino – Monte Bianco”), which had started at 9:00pm Wednesday, began to come through. Elite runners with only four hours on their legs, they flew by me as if I were standing still. Maybe it wasn’t fair to compare myself to them, but the contrast still didn’t feel good.

I was starting to fray mentally. This took many forms. I would sometimes sing to keep myself awake, any song that came to mind. I don’t think I ever finished one. I would talk to myself out loud. The trail would get easier for a moment and I’d ask “Maybe the hard part is over?” Then it would get hard again and I’d say “Of course it’s not over. It’s never over. Because this is hell. And hell doesn’t end. Hell just keeps going on and on, forever. This is just how it’s going to be. Just me and this trail. Forever. This is the rest of my life, until the end of time. Because that’s what hell is.” And so on. I occasionally wondered if there was anyone lurking in the darkness who could hear my inane ramblings. That thought at least made me smile a bit.

Mostly, I noticed that very basic thoughts could occupy my mind for hours. A 100k runner would pass me, going fast. I’d think to myself “I wish I could move like that.” Then I’d think: “But you can’t. You can only do what you can do. And you can’t feel bad for not being able to do things you can’t do. There are things you can do, and things you can’t. And all you can do is do the things you can do and not worry about the things you can’t. Because, when all’s said and done, all you can do is what you can do.” And so on. It seems hard to believe, but a thought like this could last for miles. Even stranger, I was aware while this was happening how absurd it was. I’d reflect on how primitive my thoughts had become, but I felt no shame, because, you know, you can only do what you can do.

Is there virtue in such mental states? A few years back, I asked my friend Jack how much he’d slept during his Tor des Geants. The answer was very little, and he added something like “Closest I’ve ever been to an enlightened state.” He was joking, but I wondered, during this year’s race and after, whether there’s something to this. The sleep-deprived extremes of the Tor do sometimes approximate states people otherwise strive for years to achieve. At some point, for example, you’ll find that you no longer suffer from “monkey mind“: the mind’s constant tendency to flit uncontrollably from one thought to another. Thoughts no longer bubble up–about work, money, relationships, politics, or whatever–because those parts of your brain have shut down. Relatedly, you’ll probably achieve something akin to “one-pointedness“: the ability to focus solely and wholly on one thing. That thing is the trail; there is nothing else. You may even achieve “bare attention” as you observe your own journey–both mental and physical–in a dispassionate and detached way. Perhaps it’s cheating to achieve these things by simply exhausting your brain–which, once recovered, will be as monkey-mindish as ever. But then, some advanced Buddhist practitioners deliberately engineer grueling trials–a week without sleep, the endless walking of Mount Hiei–to help them achieve such states. So maybe that’s how we get there, and maybe there’s value in seeing what these states are like.

My own state was pretty bad by the time I reached Oyace, at 3:51am Thursday. As I approached the community center that houses the aid station, I saw a huge pile of 100k bags. Oyace is not a Tor des Geants lifebase, but the follow bags suggested that it is one for the 100k. I went inside and had some pasta, coffee and soup. I’m not sure how long I was there, but probably a while. I put my head down on the table, wanting to use one of the numerous cots but feeling I couldn’t sleep again so soon. I checked the WhatsApp thread. Everyone was still hanging in there despite various problems: Megan had blisters; Mark’s knee hurt; Colleen had a bloody nose. I helpfully informed them that the descent to Oyace was a medieval torture device. Then I accepted the inevitable and went back into the night.

As tired as I was, I was looking forward to the long, steep climb to Bruson Arp and Col Brison–for the simple reason that it was uphill, not downhill. I still had some strength; I just couldn’t keep punishing my legs with these descents. The climb was fine, but sleep deprivation was really kicking in. I had mild hallucinations: for example, a headlamp above me would look like an aid station. I’d start to nod off and would meander side-to-side as if drunk. That was bad, since the left side of the trail was, in places, a steep cliff and potentially fatal fall. The trail was smooth and solid, so there was no reason anyone should stumble off–unless, of course, they’re falling asleep on their feet. I began slapping myself in the face to stay awake.

I realized I couldn’t go much farther without sleeping again. Unfortunately, the next sleeping facilities were at Ollomont, a place I’d vowed never to sleep again (it’s awful). But I saw little other choice, so I resigned myself to that fate and trudged on.

It began to get light around the time I got to Col Brison. I was seeing this section in daylight for the first time, and the views were beautiful. I stopped briefly at Berrio Damon to take some pictures, then began the descent to Ollomont.

The initial descent toward Ollomont is not hard: lots of switchbacks and not too steep. But the morning sun had failed to revive me, and I struggled to keep my eyes open. I decided I’d have to nap by the trail, but I couldn’t do so here. There was no level ground on either side; I’d have to wait for better terrain.

That didn’t take long: while still high up, I reached a flat, grassy patch by the trail. I took off my pack, put on my base layer and down jacket, and lay down to sleep. The main 100k pack had just caught up with me, so numerous runners passed by while I lay there. But that was fine, as my earplugs and headphones blocked the noise. I woke up after 25 minutes due to the freezing cold, got up and put on my rain pants, and tried to get back to sleep. No luck: it was too cold, so I got up for good. I realized I’d been carrying my bivvy sack this whole time, which could have kept me warm(er), and I was annoyed with myself for not remembering it. But still, my 25-minute nap had helped a lot.

I felt a lot better on the remaining descent: legs still hurt, but at least I was awake. I was glad I’d no longer have to sleep at Ollomont. I arrived there at 9:47am and saw Tom, who’d left Rifugio Lo Magia before me. I got some potatoes–sadly undercooked–and ate them while sorting through my gear and checking the WhatsApp thread. Megan said she’d gotten caught in the 100k pack on her climb out of Oyace, and was bothered by the conga lines and all the poop on the trail. I sympathized and was glad a lot of those runners had passed me in my sleep. At 10:27am I checked out, used the bathroom, and got underway.

The climb out of Ollomont felt staggeringly different from last year. Then, I was alone in the dark, and as I approached Rifugio Champillon and Col de Champillon, it began to snow heavily. Now it was sunny and extremely hot, and I was surrounded by 100k runners. It was nice to see what the course looked like, but I also missed the quiet beauty of last year’s night trek through the snow.

When I reached Col de Champillon, I stopped and took an ibuprofen: my first and only of the race. I didn’t need it now–at least, no more than I’d needed it for days–but I was preparing for the long runnable downhill after Rifugio Ponteille. I knew that would be my best opportunity to make up time, and I wanted to take full advantage. I figured I’d take the ibuprofen now so it would kick in by the time I got there.

As it turned out, I probably jumped the gun. Like so many of this year’s descents, that from Col de Champillon was longer and harder than I’d remembered, and it took over an hour to reach Ponteille. Then it took a while longer to get to the downhill. But once I got there, it delivered. I was able to relax my legs and fly down the runnable fire road, blowing past several runners. I reached Bosses at 4:01pm.

On my way into Bosses, I did some quick calculations. According to the timetable, I had 29k left to go. If I wanted to finish before midnight, I had 8 hours. That meant I had to average 3.6k or 2.25 miles per hour. That seemed feasible, but I’d have to get in and out of aid stations quickly. I stopped at Bosses for only two minutes: just long enough to fill my flasks and grab some dried mango and pineapple, which had become my primary fuel.

I moved as fast as I could along the paved road out of Bosses, hiking the uphills and running the downhills and flats. After a short while, I caught up with another runner who turned around and said “Yuch!” It was Ely, who I hadn’t seen since Donnas. He was having some kind of hamstring issue and I was in a hurry, so we talked only briefly before I left him behind. I heard him shouting words of encouragement after me, which gave me a much-needed boost.

Once you leave the paved road, the approach to Rifugio Frassati and Col Malatrà is absolutely breathtaking: a wide green valley that feels too big to be true. I had my foot on the gas continuously now, spurred on by the vistas and the likely-but-uncertain prospect of finishing before midnight. I was in good spirits, dampened only slightly by the long, blood-soaked piece of toilet paper that waved, at face level, from a Tor flag on one bank of the trail. Seriously, WTF??? That was not an accident: some sociopath had placed it there.

I saw few Tor des Geants runners here but caught up with a huge pack from the 100k. It’s great that the Tor races–all five of them (30k, 100k, 130k, 330k, 450k)–have been so successful. But it’s also true that sharing the course changes how it feels. The runners who surrounded me now didn’t share my experience: they were not at the end of a sleep-deprived four-day journey but had been out here only 20 hours. Their race was as valid as mine, but we had no bond. At the end of this journey, I wanted to be with my people. Instead, I felt like I’d wandered into someone else’s race.

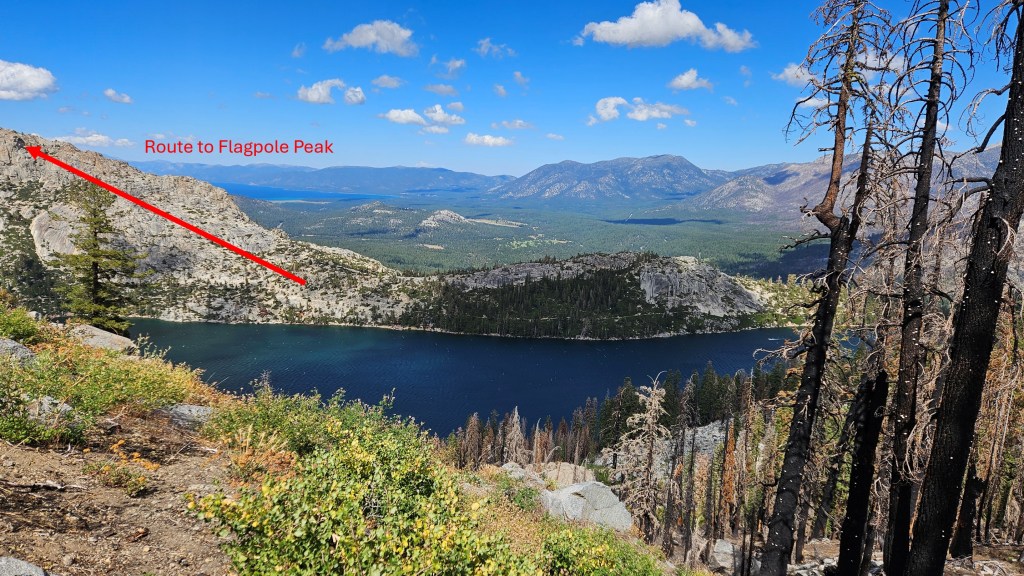

Fortunately, I left the 100k pack behind by the time I got to Rifugio Frassati. Conscious of the time, I stayed just long enough to fill my flasks and grab some dried papaya, then hurried toward Col Malatrà. The sun was already behind the ridge–I’d reached Frassati at 6:16pm–but I thought I could still reach Malatrà in time to see the sun set.

Malatrà is one of the easier cols in almost every respect. It’s not steep, and while it’s slightly technical toward the top, with ropes and iron steps, I wouldn’t call it scary. Yet, it’s arguably the most memorable col. This is partly because it’s the last: the beginning of the end; all downhill from here. But it’s also visually arresting, the trail gradually climbing a barren escarpment to pass through jagged teeth. Those teeth form a gateway runners pass through, heightening the sense that you’ve formally entered the endgame.

I was looking forward to that endgame as I hiked the final ascent through the scree. I heard a drone above me and wondered if I’d make it into a Tor video. I thought this spot would make for spectacular footage, and apparently the Tor folks agreed with me, as it provides the first few seconds of this year’s highlights video. I can’t say if that footage was taken when I was there, but judging by the cloud cover (present in the video but not in my photos), I suspect not.

Passing through that gateway was an almost religious experience. (Not quite on par with reaching the Bridge of Heaven in the Ouray 100, but close.) The emotional impact of seeing Mont Blanc and the valley of Courmayeur was huge, and heightened by a glorious sunset. There are times when you feel like you’ve stepped into heaven.

The initial descent from Malatrà is smooth and gentle: I expected to enjoy it and did. I was moving at a decent pace with little effort, and the views kept me enthralled. I stopped too often to take pics, but when you see giant thistles against a backdrop like this, what are you going to do?

The good times didn’t last: the trail got a lot steeper and more technical, and my legs forced me to slow down again. The “trail” through this stretch was a series of deep, narrow parallel ruts, formed by the passage of many feet and the springtime snowmelt that followed their tracks. When those feet had worn one track into a deep enough rut, other feet would seek an alternate path–which would eventually become deep enough to force other feet onto another path, then another. The resulting landscape was difficult to traverse quickly, though occasionally some runner with fresher legs than I would fly by and prove it wasn’t that hard.

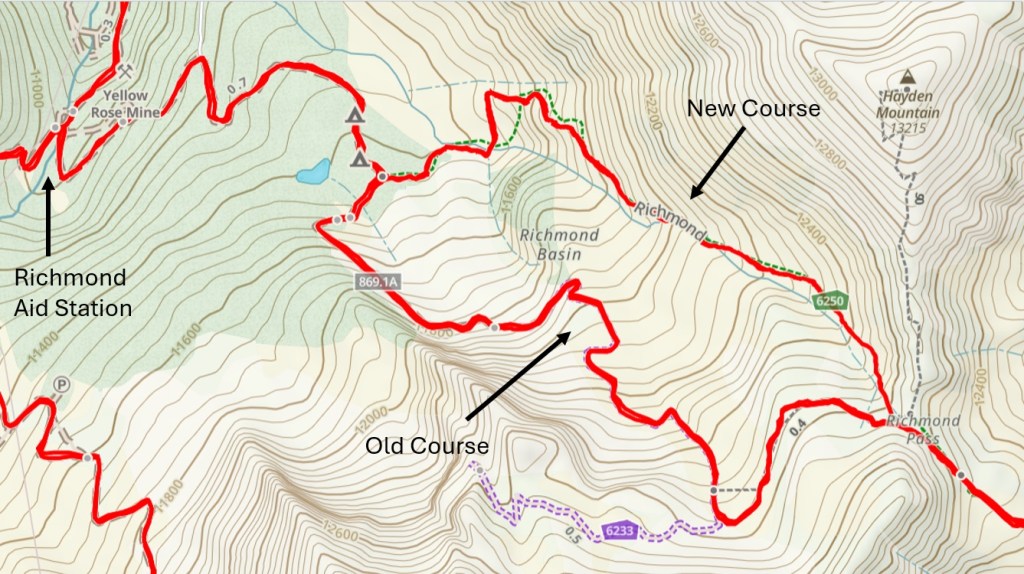

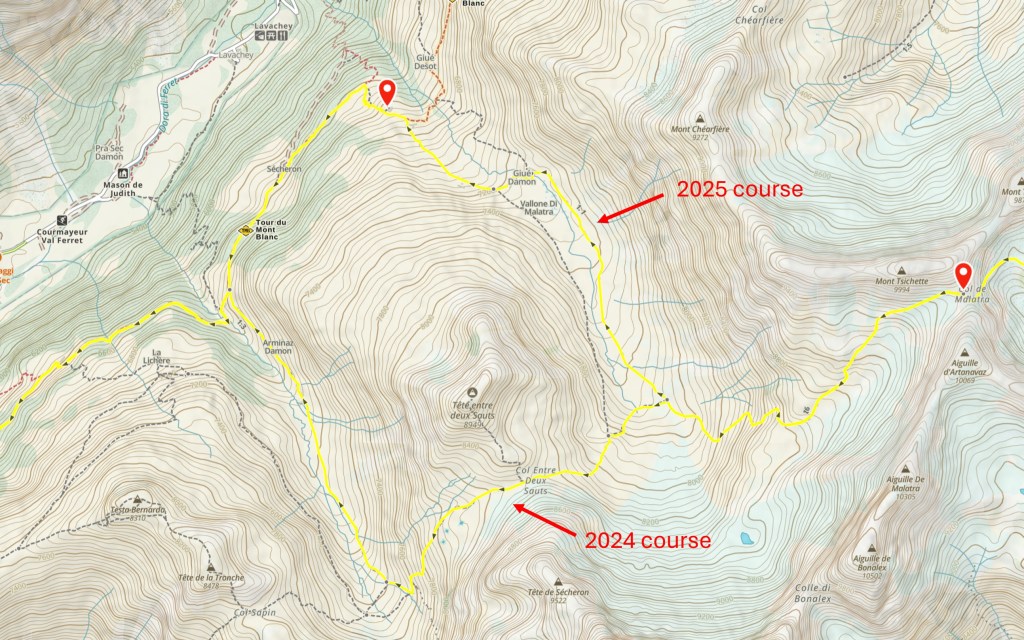

This last leg of the course had changed: whereas last year’s went south to Pas Entre deux Sauts, this year’s went north to Rifugio Bonatti before rejoining the old course at Arminaz Desot. This didn’t change the distance or elevation gain, but it did change the views, and I approved. The new course brought us into a wide valley that provided a spectacular frame for the mountains beyond, most notably Mont Blanc and Mont Maudit (I think). These would be my last views before dark, and possibly the best of the race.

I hobbled into Rifugio Bonatti and was overwhelmed by an enthusiastic volunteer, who wanted to give me a tour of everything they had to offer and insisted on helping me with everything. My longstanding gripe about American aid stations is that volunteers are sometimes too determined to help. I know they mean well, but it can feel overwhelming to be barraged by questions and assistance when you’re exhausted and need a minute to think. Sometimes they’re so aggressive that I have to be blunter than I’d like in asking them to leave me alone. This seems a peculiarly American thing: I’d never encountered it in Europe–until now. I eventually threw up my hands and said “Un momento! Per favore!” The volunteer got the message, laughed, and backed off.

I asked how far it was to the finish. The volunteer told me 14k: seven to Rifugio Bertone and seven from there to Courmayeur. It was a little after 8:30, so I had less than three and half hours till midnight–i.e., I’d have to average better than 2.5mph. That worried me a bit. I knew the final descent to Courmayeur was super technical and, at least for me, would be very slow. On the other hand, I recalled the balcony trail between here and Bertone, which skirted the rim of the valley, being smooth and runnable. I decided I needed to run the balcony trail as fast as I could, so it wouldn’t matter how slow I was on the descent.

I ran it pretty fast: faster than I’d run all race, except for maybe the long downhill to Bosses. Fast enough to fly past several people who’d passed me on the descent to Bonatti. Fast enough to make my light belt bounce annoyingly. I wondered if I was redlining too hard, but I knew I’d be slow on the final descent, and it was taking me longer than I’d hoped to reach Bertone. So I kept my foot on the gas.

I reached Bertone at 9:47pm. After finishing, I learned from the WhatsApp thread that my predicted ETA at Bertone was 10:30. I’m guessing that, because I was slow on the descent to Bonatti, the Tor’s algorithm extrapolated a slow pace to Bertone. And many runners indeed slowed down on the latter stretch. There are, as I said, all kinds of runners–which is why we should take the algorithm’s forecasts with a big grain of salt.

The volunteer at Bonatti had led me astray: he’d said Bertone was halfway to the finish, but in fact it had been 8k from Bonatti to Bertone, and only 4.5k from here to the finish. I now had over two hours to go the remaining 2.7 miles. I could have taken the balcony trail a little easier, but I was glad to have the cushion now.

I needed it. The final descent to Courmayeur is bunch of fixed, jagged rocks that barely deserves to be called a trail. It was slow and painful, and I found myself wondering why anyone would create a “trail” like this. Maybe it’s not so bad on good legs: Megan and I had moved much faster last year. But now, this seemed like a last Purgatorio before Courmayeur.

I reached the road and stopped to put my poles away. Someone ran by, urging me to run with him. I told him to go on, but a minute later I caught and passed him. The last mile through town was quiet and uneventful, except that, after passing through some kind of tracker at Parco Bollino, I started to worry about the tag that all runners are supposed to keep tied to their packs–and which I’d lost early in the race. (There’s a story there, but not one worth telling.) Would it matter that I’d lost it? Would I not get an official time? Apparently it didn’t matter: when I finished, at 10:48pm, the volunteers welcomed me with a “Bravo, Daniel!”

I signed the finishers’ board, sat down, and texted “Courmayeur in. Yuch out.” to the WhatsApp group. I felt dazed and wasn’t sure what to do, so I had a beer and scrolled through my messages. Garret was quick to congratulate me on beating his time, if only barely. He’d also been giving moral support to Megan, which was good, since I’d been in no position to do so. She’d been having late-stage problems, texting from Ollomont that “I feel sick and my knee is shutting down–2023 + 2024.” But she’d left Ollomont and had reached Bosses, so I was hopeful she’d be ok.

I really needed some solid food, having eaten nothing but dried/candied fruit for many hours. But they didn’t have much besides sweets at the finish, and I’d left my credit card in my follow bag and couldn’t buy anything. So I accepted a ride to the Sports Center along with Jorge, the runner who’d finished one minute before me. We talked about our races, and I learned that he’d slept 17 (!) hours along the way. No wonder he looked so good.

No real food at the Sports Center either, but it felt amazing to take a shower, and to lie down on a cot knowing I could sleep as long as I wanted. I slept around eight hours and woke to a beautiful view of Mont Blanc through the Sports Center window.

I also woke to see Megan. She’d finished at 7:45am and had just arrived at the Sports Center. I was elated to see her, and that her race had worked out. Despite her struggles, she’d finished strong in 117:45, fourteen hours faster than last year. I gave her a hug and she told me I looked awful (or maybe she told me that retrospectively; can’t recall). Although I was feeling much better, the post-race swelling had set in, and my face (and other parts of my body) were getting swollen and puffy.

I gave Megan my cot and went in search of food. There was still nothing in the Sports Center or a nearby cafe, so I walked into town and got three slices of my favorite focaccia (onion) from Pan Per Focaccia, then sat down to eat it on the steps of Chiesa di San Pantaleone. A runner who’d finished shortly behind me–a Slavic guy, maybe, with long graying hair–came up and said hi, and we spent a few minutes comparing notes. It was a beautiful morning, and I felt grateful for all of it: the sun, the square, the friendly words, the focaccia, and being done.

Megan and I spent the next couple of days seeing our friends come in–first Mark, then Marie, then Mat, then Colleen, then Noe–and attending the awards ceremony, which seemed interminable this year. I’m not sure if it was handled differently than last year’s, but I didn’t remember it being so long. Still, it was nice to have something to bookend the whole experience, and to see everyone one last time.

Was I happy with my race? Yes. My time of 108:48 was 23 hours faster than last year’s. Pretty much everything went, if not perfectly, about as well as I could have hoped. It’s true that I made the one big mistake of trashing my legs on that first descent, and that I missed my A goal. But it’s also true that I’ve never hit any of my A goals. That doesn’t mean these goals are delusional, but they do constitute a kind of theoretical limit: what’s possible if everything goes right. In the real world, that doesn’t happen much. I don’t even hit my B goals very often, and I’m always happy when I do.

Happy enough that I feel no need to do this race again. I love the Tor, but it’s really hard, and the novelty is gone. I’ve gotten what I can from it: a deep relationship with a special place, some amazing friends, whatever ineffable psychological or spiritual changes such a journey brings about–even if I don’t know what those are. In The Last of the Giants, Doug Mayer’s wonderful graphic novel, Mayer writes that “When you finish Tor, you’re a different person. Different and with a greater understanding of yourself, the world, and your place in it.” I can’t make such lofty claims. All I can say with confidence is that running the Tor has taught me what it’s like to run the Tor. And that’s enough.

Tor institution Ivan Parasacco has told runners to “Take a photo at the start and then take a selfie at the finish. Not only just to see your face, but to see what you have done. To see the changes in your eyes. To get a picture of how you have changed.”

Here are my pics, for what they’re worth: