Last December my friend Garret asked if I’d pace him at Hardrock. I leaned toward “yes,” but Colorado’s San Juan mountains are not close, so I wondered if I could get more out of the trip than a pacing gig. I recalled another race in the same neighborhood–the Ouray 100–which turned out to be only one week later. Good enough: I’d pace at Hardrock and do Ouray the following week.

YouTuber Simon Guerard describes Ouray as Hardrock’s little brother–where “little” means younger, less established, and in need of validation. This is his explanation for Ouray’s absurd elevation gain. While Hardrock is legendary for its 33,197 feet of climbing, Ouray ups that ante by 26 percent, to 41,862 feet. That’s 410 feet of climbing per mile, for 102 miles. My hilliest prior ultras were the Tor des Geants (381 feet per mile), the Ben Nevis ultra (364 feet per mile), and the Swiss Peaks 100k (319 feet per mile). (Also the mostly off-trail Desolate Peaks–431 feet per mile–but that’s a different kind of beast.) Those are not easy races, but Ouray was something else. I hadn’t done any previous 100Ms with remotely this much vert, so I had no idea how long it would take. I set myself an A goal of 36 hours, a B goal of 38, a C goal of 40, and a D goal of “in time to make my flight.”

The course begins and ends at Ouray’s Fellin Park. It consists of multiple out-and-backs that climb to the surrounding peaks, as well as a large (Ironton) loop that runners do in both directions. While some might find this a contrived way to rack up distance, I thought it worked well. The “outs” and the “backs” felt completely different, as one is uphill and the other downhill, and they go in different directions. Moreover, this structure allows you to see other runners again and again, making this an unusually social and supportive race. That support would prove helpful as the miles added up.

I left San Rafael on Saturday July 5, taking Highway 50–the “loneliest road in America”–through Nevada. I hadn’t been that way in years, but if you’re going to drive across Nevada, it’s the way to go. The highway is lonely but beautiful, passing through high desert and small towns like Austin, Eureka and Ely. I camped that night at Cave Lake State Park and did a short run there the following morning before moving on.

I arrived in Silverton Sunday evening and went straight to the Molas Lake campground, where I’d spend the next eleven days. I planned to spend my first few days running as much as possible to get used to the altitude. Molas Lake served this purpose well, as it’s above 10,000 feet, has showers, and is on the Colorado Trail. That trail isn’t particularly hilly, but I wasn’t looking for conditioning at this point–just getting acclimated to the thin air. I logged 75 miles over the next three days.

On Friday-Saturday I paced Garret from Animas Forks to Telluride, logging another 30 miles. With Garret’s race out of the way, I could now think about my own. I’d logged a questionable 105 miles in the last week, so this mostly meant rest. I’d done all the training I could, and it was time for a hard taper.

Megan flew into Montrose on Wednesday, where I picked her up and returned to Molas. On Thursday we headed back down to Ouray, where we’d spend the night at the Amphitheater campground. We strolled around Ouray, checked in for the race at Fellin Park, and grabbed a quick pizza dinner. Ouray, I should say, is a charming little town. It sits in a valley at 7,800′ but is surrounded on all sides by towering cliffs and peaks. It boasts a lot of pretty old buildings as well as natural hot springs, which we hoped to soak in after the race.

In the days leading up to the race, I worried about two things. One was the weather: the forecast predicted days of thunderstorms and rain. I didn’t love the idea of traversing exposed peaks with lightning coming down, or of navigating the technical parts on muddy, slippery ground. (I was worried enough about the footing to make myself a pair of screw shoes before the race.) In the end, however, the RD’s admonition to never trust the forecast proved correct. Thursday was warmer and drier than predicted, and this unexpectedly good weather continued for the next few days.

My other worry concerned my D goal (finish in time for my flight). Due to some unwise planning, the D goal was effectively also the C goal (under 40 hours). For reasons that don’t matter here, I’d decided to fly from Salt Lake City to Hartford at 7:45am Monday. This meant I had to be in SLC Sunday night, which meant I had to drive up there Sunday. This would be fine if I could sleep Saturday night, but this basically meant finishing under the 40 hours that would get me to the finish by midnight Saturday. This wasn’t a crazy goal, but in previous years, only about ten percent of starters had managed it. I didn’t expect to flirt with the race’s 52-hour cutoff, but if my race stretched to even 44 or 46 hours, I’d be screwed. I couldn’t drive the eight hours to SLC after two grueling nights without sleep. In retrospect, my flight plans were an act of hubris that caused me a lot of avoidable stress.

The race had a late (8:00am Friday) start, so I was able to sleep well the night before. We packed up camp, went to the start, got my GPS tracker, and then I was off. Megan planned to start pacing me at Weehawken 2 (mile 58), so I didn’t expect to see her until after midnight. My plan was to average 3.5 mph as long as I could, which would get me to Weehawken 2 at 12:50 AM. This was not a sustainable pace–it implied a finishing time of 29:10, a course record–but it seemed like a reasonable first-half target given that the second half is harder, and I expected to slow down.

The first six miles were straightforward and familiar to me from Hardrock: a short single-track took you through a stone tunnel and over a gorge-spanning bridge, then spit you out on Camp Bird Road, which climbed gradually toward the Lower Camp Bird aid station. From there we took a right fork that led to the first turnaround at Silver Basin. This out-and-back was forgettable–mostly jeep road through dense woods–but opened up into a nice meadow with an alpine lake at the top. I followed the trail to the hole punch at the turnaround, punched my bib, and headed back down.

After returning to Lower Camp Bird, I headed south to the Richmond aid station. From there, a short stretch of jeep road led to the Upper Camp Bird junction, the nexus for the next two out-and-backs. The first was a single-track trail leading up to the Chicago Tunnel, an old mine entrance. This climb was steeper and more technical than the previous one, and also prettier. I was still close enough to the leaders to see them coming down, so I cheered them as they passed. I felt pretty good and passed a few people myself, reached the top, punched my bib, and headed back down.

The next out-and-back led to Fort Peabody, the race’s highest point (13,365′). I loved this section. Although it was mostly jeep road, the road was rocky, technical and steep enough to feel like a trail. It was also completely exposed, providing stellar views all the way up and down. My only gripe about this jeep road–and others to come–was that it had an awful lot of jeeps. Like, big convoys going up and down the mountain. Sometimes a convoy would stop for minutes while letting another pass, giving passing runners good whiffs of exhaust. This wasn’t anyone’s fault–we were all just out there enjoying the trails–but this much traffic in otherwise pristine outdoors was an unpleasant surprise.

Traffic aside, I felt good on the climb to Fort Peabody, passing quite a few people along the way. The last quarter-mile was a single-track through a scree field. The views from the top were stupendous.

The descent was fun, as descents on fresh legs tend to be. I was, however, having issues with my pack. I’d decided I needed a larger pack for this year’s Tor des Geants, so I was trying out a Salomon Cross Season 15 instead of my usual Advanced Skin 12. I’ve mostly been happy with it, but I’ve noticed that some problems arise when it’s fully loaded (as it was now) and when I’m running as opposed to hiking. The right shoulder binds in ways that cause discomfort and chafing, and no amount of fiddling seems to fix this. I think the problem is that my body is asymmetric (right shoulder larger than left), and this pack’s water-resistant material doesn’t stretch to accommodate my asymmetries. The threat of chafing worried me, but there wasn’t much I could do right now, so I tried to ignore it.

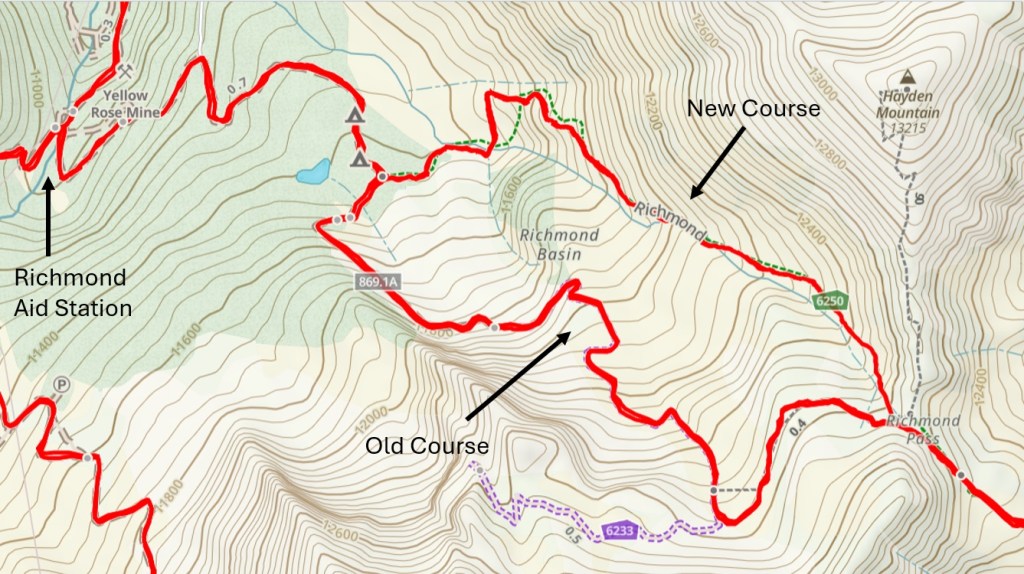

I returned to the Richmond aid station, then headed east toward Richmond Pass. We’d received an email the day before, with an attached GPX, saying that this year’s race would include the restored historic Richmond Trail. I’m glad it did, because this section was gorgeous. Both the climb to Richmond Pass and the descent down the other side had fantastic views and riotous wildflowers. (Note: the new course is slightly shorter but also steeper and more technical, so probably a wash in terms of time.)

This was also the slowest part of the race so far. I’d maintained my 3.5 mph average to Fort Peabody and was comfortably above it by Richmond 2. But the climb to the pass was steep, technical and often overgrown, and I fell behind my target pace for the first time. The descent helped, but less than I’d hoped, as much of it was too steep to move fast. By the time I hit Highway 550 and ran the short flat stretch to Ironton, I was back on target pace, but barely.

Ironton is a major milestone: runners pass through it three times (at miles 27, 35 and 43), so it’s a well-supported aid station with lots of crews. I heard someone call my name as I arrived and was pleasantly surprised to see Megan. She hadn’t planned on coming here, but it was easy to reach and she’d spent enough time in Ouray, so here she was. We passed through a sea of cars to reach the aid station.

I didn’t stay long, just grabbing some Gatorade packets and a bag of potato chips before starting the counter-clockwise loop. The first few miles were bland: a steadily rising red-dirt jeep road through the woods. That was fine with me: after the eye-popping but challenging Richmond Pass, I welcomed the steady, mindless climb.

As the road cleared the treeline, the views of nearby Red Mountain got better and better. I’d been intrigued by these iron-ore hills throughout the race, so I was glad to get a close-up now. As I crested the loop’s high point, I saw the race leader coming toward me. He was moving fast and was now about eight miles ahead. We exchanged some supportive words and went on our way.

The jeep road rolled for a while, then ended at a single-track that descended sharply. Good: that meant the clockwise loop would probably be faster, as it would involve a steep climb and a more gradual, runnable descent.

Megan was still at Ironton when I got there. She filled my flasks as I drank some ginger ale and looked for food. I took a potato-and-cheese quesadilla, said goodbye to Megan, and ate the quesadilla as I walked back to the loop. Megan said she probably wouldn’t be there when I returned, so we agreed to meet at Weehawken 2 on a 3.5 mph schedule. That now seemed optimistic, but not impossible.

The clockwise loop was fine, and different enough to not feel repetitive. While the first loop allowed me to see all the leaders, I now greeted everyone behind me. The race was pretty spread out now, and as I finished my second loop there were still a few runners starting their first–meaning they were 16 miles behind me and 24 behind the leader.

I’d been pondering whether to change my shoes at Ironton 3. I’d been running in Altra Mont Blancs, and those still felt fine, but I nonetheless put on a new pair of socks and the Altra Olympuses in my drop bag. I didn’t have any reason to switch beyond “maybe it’ll feel better,” but it gave me a chance to ditch the moleskin I’d placed over my toenails, which had been coming loose for hours.

Between the shoe change, a visit to the porta potties (which, annoyingly, had no toilet paper), and fishing batteries and such from my drop bag, I spent more time at Ironton than I’d hoped. I grabbed another two potato-and-cheese quesadillas for the road and got underway, eating the first enroute to Highway 550 and sticking the other in my pack.

The climb back up to Richmond Pass nearly broke me. It was steep, long and hard, rising 3,000′ in 2.7 miles. I compared it mentally with the Tor’s most grueling cols and thought “the Tor has nothing on this.” At some point a blond guy with a ponytail passed me, looking strong. I didn’t care about my place, but the contrast between us was dispiriting. I trudged up, watching him recede into the distance.

I told myself not to worry about the pace: just keep moving forward. This, at least, I did. It got colder and windier as I climbed, but I held off on my jacket, not wanting to overheat. I saw lightning in the distance, but overhead there was nothing but stars. I turned off my light to admire the beautiful, moonless sky. I saw a shooting star and wished for a successful race, whatever that might mean.

At last I reached the snow that marked the top of the pass. I crossed over and began the descent, which seemed steeper than it had on the way up. Between the grade and the growth along the trail, it was slow going. I felt wasted by the time I reached Richmond for the third time.

The aid station volunteers asked how I was doing, and I replied that Richmond Pass was hard. They said that seemed to be the consensus. I topped off my flasks, drank a little veggie broth, and tightened my shoes to stop my feet from slipping forward. I was starting to think the Olympuses were a mistake, as I’d been jamming my toes all the way down.

I headed down the fire road toward Weehawken. I was glad to be heading that way, both for the gradual downhill and the prospect of seeing Megan. The downhill helped less than I’d hoped, as it was very rocky, but I was doing better than a runner I passed who’d apparently lost his downhill legs. Eventually the road smoothed out, and I made good time from Lower Camp Bird on.

I hit the porta pottie again at Weehawken: my guts hadn’t been doing well for some time. I still had the second quesadilla I’d brought from Ironton but couldn’t stomach it now, so I looked for other fare. I’d been impressed by the aid stations at Hardrock–particularly the ubiquitous selection of vegan soups–but these aid stations were not Hardrock’s. Nothing really appealed to me, so I forced down a couple of pierogies and moved on.

The Weehawken out-and-back is short, rising 2,300 feet in 2.5 miles to the Alpine Mine Overlook, then coming back down. I climbed steadily but listlessly. I’d left Weehawken around 12:30 AM, which was faster than 3.0 mph pace but slower than the 3.5 I’d hoped for. This isn’t going to get better, I thought. I knew that, for all the vert I’d done, the worst was still to come. The runner I’d passed earlier, who couldn’t run downhill, passed me now. Great.

I was conscious of how poorly I’d been fueling since that last quesadilla at Ironton. My early fueling had gone well: I’d eaten some pizza and bananas before the race, then six Lenny and Larry’s cookies (1300 calories), six Gatorade packets (1100 calories), two ziploc bags of potato chips (~500 calories), the first quesadilla (~500 calories), and a few hundred calories of ginger ale before Ironton 3. Since then, however, I’d had only the one quesadilla and a couple of small pierogies. I wasn’t nauseous, but my guts felt off and I had no desire to eat anything (or drink any more sports drink, the thought of which made me sick). This had to change. I pulled out a cookie and forced it down with a lot of water to make it easier to chew.

The blond ponytail guy who’d passed me on Richmond descended and said there was a beautiful crescent moon at the overlook. I reached it a few minutes later, and there was indeed a nice view of Ouray 3,000 feet below. I exchanged a few words with the runner who’d passed me going up, punched my bib, and headed down. He still couldn’t run downhill, so I quickly left him behind.

Megan was waiting for me at Weehawken. She’d been waiting a while, as I was over an hour behind 3.5 mph pace. I wanted to leave quickly, as I had all race, so I wolfed down a banana and took another for the road. We headed out toward Hayden Pass. I told her I’d been having a rough time. I was feeling my 21,000 feet of climbing, but the heavier burden was the knowledge that I was only half done. It pained me to think of doing it all again in the remaining 40 miles. And my mental clock was constantly ticking: 40 hours, 40 hours, 40 hours. I was still on roughly a 32-hour pace (~3.2 mph), but I knew I’d slow.

The climb up Hayden Pass wasn’t too bad, although I had to stop and sit down once. I wasn’t dying; just feeling weak. The single-track snaked through innumerable switchbacks, and it was a relief to finally break through the treeline and emerge onto an open ridge. It was light now, but I wasn’t paying much attention to my surroundings: just keep moving forward. The trail rolled along the ridge for a while, then began to descend–steeply. My immediate thought was “we’ll have to climb this again.” Every step of this super-steep descent filled me with dread.

When we reached the Crystal Lake aid station, Megan insisted that I sit down for a while and eat. I plunked myself into a chair for the first time all race. The volunteers were cooking bacon and eggs but didn’t have great veggie/vegan options. They did, however, give me some ramen noodles in veggie broth (which took a while to soften) and mixed up some instant mashed potatoes. Neither was amazing, but I got the half-softened noodles down and mixed the broth with the mashed potatoes. Best nutrition I’d had in some time.

Blond ponytail guy was there, looking tired, as was a younger blond guy, Sam, we’d been see-sawing with for some time. No one seemed in a hurry to leave. I noticed through the mesh pocket of my pack that my phone screen was lit up, and Gaia appeared to be recording a track. Sometimes the constant jostling of the pack will turn various apps on, which is annoying and drains the battery. I didn’t think about it much, but turned off the screen.

The break was nice, but we couldn’t stay here forever. I hoisted my pack, which weighed a ton. I had a lot of stuff in there: rain jacket, rain pants, base layer, gloves, emergency bivvy, two lights and extra batteries, phone, battery pack to charge the phone, GPS tracker, a bag of stuff that the race had provided and required us to carry at all times, and of course food and water. Aside from one light, food and water, I hadn’t used any of this stuff all race. It seemed like a wasteful burden, but I was stuck with it for now.

We began the climb back up to Hayden Pass. It was hard, but not as bad as I’d expected. My extended rest and the meal at Crystal Lake seemed to have done me good, and I was glad Megan had insisted on the break. While it’s good to get in and out of aid stations quickly, this go-go-go approach had stressed my system to the point where I couldn’t really eat. Taking 20 extra minutes at the aid station was worth it if it allowed me to get some real food down. We passed blond ponytail guy and Sam, as well as a lot of runners coming the other way.

The daylight also helped. I hadn’t really noticed the scenery on the way out, but this section was beautiful, lined with weird rock formations and wildflowers. I pulled out my phone to take some pictures but found the battery completely dead. Rats: the phone had been at 95 percent at Ironton 3, but apparently my pack had turned on a lot of apps. I took out my battery pack to start charging the phone, but this would take a while. Fortunately, Megan got some great pics along here.

We made good time on the descent from Hayden Pass. I was happy that my downhill legs were holding up, but I worried about the toll of all this braking. I’m pretty good at coasting down moderate grades without braking, but these descents were too steep for that, and my legs were starting to feel trashed. I was slaloming a lot on the last stretch of jeep road just to avoid too direct a descent.

We reached Camp Bird Road and took it back to Fellin Park. There were some spectators lining Oak Street, who looked me up and cheered me on by name. At some level I appreciated this, but I felt too tired to respond with more than a desultory “thanks.” I was worried about my pace, which had fallen below 3.0 mph, and it had gotten really hot. The previous day’s cloud cover was gone, and the direct sun at this altitude felt oppressive.

I wasn’t optimistic about breaking 40 and thought I might DNF. This was a depressing thought, as I knew I was capable of finishing the race. My real constraint wasn’t my endurance but the schedule I’d foolishly committed to. I wished I’d made different choices. But, I didn’t have to make any choices now. Whatever was in store, I could at least do the next out-and-back. And I had one thing going for me: I’d been able to ditch my excess gear at Fellin and now felt way lighter.

The next section took the Old Twin Peaks trail to Twin Peaks, a couple of rock spires high above Ouray. It then descended to the Silvershield aid station before climbing back up and descending again. The first part of Old Twin Peaks looked pretty sketchy, and Megan said “I didn’t sign up for Desolate Peaks!” Desolate Peaks is a highly technical event in the Desolation Wilderness, and while this wasn’t that, the trail did involve some exposed rock and dilapidated steps barely held in place by old iron stakes. The Ouray Trail Group website notes that “Around 300 steps were placed using rock, logs and 4x4s, and 607 feet of cribbing was placed to help hold the trail in this very steep gorge.”

The trail eventually improved, but toward the top it also got really steep. From bottom to top, Old Twin Peaks climbed 2,800′ in 2.2 miles, but even this steep average grade included long flat sections. So the steep parts were steep indeed. At least some cloud cover eventually came in, so it was relatively cool by the time we reached the top. We clambered up the rocks, punched my bib, and headed back down.

Our “local group” of racers had been stable for a while, and we saw the same faces again and again on the out-and-backs. First there would be a dark-haired guy, then a woman (the second female), then a bearded guy who was finishing strong and had been dropping his pacers. Blond ponytail guy was a little behind us, while Sam would sometimes pull ahead and sometimes fall behind. We’d see others further ahead and behind, but these were the faces we could count on within 5-10 minutes of the turnarounds.

We saw them all on our way to and from Silvershield, on Highway 550 at the foot of a long gradual descent. It was uncomfortably hot down here, making the climb out a chore despite the moderate grade. We reached the top and headed back down Old Twin Peaks. Megan had worried that I’d drop her on this technical stretch, but she kept up fine and soon we were back in Fellin Park.

The Fellin aid station was serving freshly made pizza, so we each grabbed two slices and ate them while walking to the Perimeter Trail. This is a well-maintained trail that starts across 550 from the hot springs, skirts the cliffs that overlook the town, then rises more steeply past the Amphitheater Campground where we’d stayed Thursday night. Along the way it passes Cascade Falls, a gorgeous waterfall that drops hundreds of feet before misting the spur trail below. We saw hikers cooling off at the base of the falls and were tempted to join them, but I didn’t want to spare the time.

Not far past the falls, we caught up with the bearded guy’s pacer. The two had passed us at the start of Perimeter, but the pacer had been unable to keep up, and now he was soldiering on alone. We also passed and left him behind.

As we climbed toward the turnaround at the Chief Ouray Mine, I began to feel something I hadn’t felt in hours: hope. This whole out-and-back had a much gentler grade than previous ones, which meant not only a quick ascent but also–more importantly–a runnable descent. For most of this race, I couldn’t make up on the downhills what I’d lost on the climbs because the downhills were too steep to run. It’s not like this section was flat: the main climb rose 2,000 feet in two miles. But the grade was more or less constant, so the average grade was also the actual grade–which was something I could run. I estimated that, if we kept our foot on the gas, we could get back to Fellin by around the 33-hour mark, leaving just the final 10.5-mile stretch. If we could average 2 mph on that, we’d finish in the neighborhood of 38 hours.

I shared my thoughts with Megan, who agreed that we were in good shape. We pressed on to the turnaround, seeing the usual faces as we neared the top (including bearded guy sans pacer). The Chief Ouray Mine wasn’t much to look at: just an old shack. I punched my bib and headed back. We must have moved quickly down the hill, as we passed Alexandra (the second-place female), who’d been ahead of us for hours, just before reaching Highway 550.

We also saw blond ponytail guy just before hitting the highway, but he was on his way up. He’d stopped to take a nap, saying he couldn’t keep his eyes open any more. I couldn’t fault him for that decision–you gotta do what you gotta do–but I was sorry to lose one of our local group.

We reached Fellin at 5:13, used the bathroom, filled our flasks, grabbed four more slices of pizza, and were enroute to the last out-and-back by 5:21. This meant we could break 38 hours by averaging 2.3 mph. That seemed doable to me, but of course it would depend on the terrain. I no longer worried about finishing before midnight–that seemed assured–but I did hope to reach the Bridge of Heaven turnaround before dark.

We left Fellin with Alexandra and chatted with her for a bit, but she wasn’t eating pizza and went on ahead. We spent a few minutes on 550, then headed up the Horsethief Trail. This rose gradually through a series of switchbacks, and we could see Alexandra up ahead. Not for long, though: she was a really strong climber and soon left us behind.

A friend had told me before the race that he really enjoyed Ouray’s final climb. He didn’t say why, however, so I was left to wonder. Was it particularly beautiful? Memorably technical? So far it was none of those things. What it was was gradual. Like the previous out-and-back, it had a steady grade–rising 5,000′ in five miles–that never got particularly steep. For hours I’d assumed this race would save the worst for last, but instead it was ending with the two most gradual out-and-backs of the day. It seemed the RD was not the sadist I’d thought.

And actually, that last climb was beautiful. Once we’d cleared the treeline, we emerged onto an open ridge with spacious views. This is my favorite kind of terrain, and I welcomed it now. But I was also very, very tired. I’d pushed hard through the previous out-and-back to gain a cushion, and I was feeling the toll now. Although the terrain was easy, I struggled to keep up with Megan and kept looking at my watch, wondering how much farther we had to go. I figured less than a mile, but I saw no end in sight, and I started to wonder how much longer I’d last. I told Megan I finally understood what people meant by “leaving it all on the trail.” I’d pretty much left it all.

We passed a strangely fresh-looking runner: another of the bearded guy’s pacers. He too had been unable to keep up with his runner, who he said had started weak but was finishing strong. No kidding: I’d never seen a runner leave so many orphaned pacers in his wake.

The last mile to the turnaround was beautiful and gentle, but things got harder and harder for me. I made a lot of pained noises. I occasionally stopped and leaned on my poles. I thought how insane it would be to come this far and not make it to the top, or to make it to the top without the energy to get back down. I felt lightheaded and wondered if I might pass out. Finally, I wondered: what was the Bridge of Heaven? Was it an actual bridge? A bridge-like rock formation? My ignorance was probably for the best: at least I had curiosity to pull me along.

Finally we saw our harbingers: bearded guy and Alexandra. They said the views from the top were amazing. But where was the top? I still couldn’t see where this all ended. At last we saw dark-haired guy descending a trail from a grassy knoll above us. I said something like “Are you f***ing kidding me?? I have to go all the way up there??” It really wasn’t far, but I was ready to be done.

We congratulated dark-haired guy as he went by and continued on to the top. The views were unreal. We’d arrived just before sunset, and the light was ethereal. We reached the Bridge, which was a narrow ridge with views in all directions. We hiked out to the turnaround, punched my bib, and stood a moment to take it all in.

It’s hard now to convey what it felt like to be there. I’d been on a pilgrimage for 36 hours just to get to this place, and I was exhausted and in a heightened emotional state. I remember feeling awe in a way that’s rare. I remember telling Megan I’d never done a race with a finale like this. I remember that we both felt incredibly lucky to arrive there at that time, able to see everything in that magical light. I felt deeply moved, grateful for this place and the journey that brought me here.

But we weren’t done. We still had over five miles left. So we left the Bridge and headed down the trail.

We passed Sam just below the summit, glad he’d make it while it was still light. I moved slowly at first, finding the downhill hard on my battered legs. But once we hit a runnable stretch, I was able to relax and let gravity do its thing. I clicked off a couple fast miles, leaving Megan behind, only slowing when the trail got steeper and more technical. The rest of the descent alternated between more and less runnable parts, with the former ok and the latter painful.

We hit 550 and jogged to the finish, reaching it in 37:52. Due to some finish-line confusion, my official time is 37:55. Unlike most races, Ouray doesn’t have a finishing chute: just a couple of small cones on the grass. I didn’t see them in the dark or realize I had to run through them, and since I didn’t run through them, no one knew I had finished. By the time I’d figured all of this out, I’d added a few minutes to my time. That’s fine: I was thrilled to finish under 38 hours and wasn’t going to sweat the change.

I was desperate for some real food, but everything in Ouray is closed by 10. Fortunately, the aid station had options I hadn’t been eating all day, like Impossible burgers. I ate two of these while checking out my new belt buckle.

I was happy with my race. I finished 14th overall (out of 137 starters), 12th male, and 1st in the 50-59 age group, despite it being a fast year for the race as a whole. Both the male and female winners (Ted Bross, 36 and Sarah Ostaszewski, 33) set new course records (29:19 and 32:42, respectively). A record 21 people broke 40 hours: over the race’s previous history, that number ranged from 2 to 12. And 60 percent of the starters finished the race, also a record high. This year’s strong performances probably owed something to the weather, which was mostly cool and rain-free. But they also continued an obvious trend: the race has gotten larger and faster with each passing year. I heard someone say that this year’s race sold out in early spring, which had never happened before. So it seems Hardrock’s little brother is growing up.

We got a good night’s sleep in a local B&B and visited the hot springs the next day while waiting for the last runners to come in. I won’t ascribe them any curative powers, but it was nice to soak my tired legs in the hot pools, occasionally alternating with a plunge in the cold swimming pool. All while taking in the views of the surrounding peaks, which, thankfully, I no longer had to climb. After an hour of this, we headed to the awards ceremony.

The ceremony was a comedy of errors. They first presented the top three females, noting that the winner had set a course record. Then, after some discussion, they “corrected” themselves, saying it wasn’t a CR after all. Except that, actually, it was. They then presented the third place male, Vernon Palm, who seemed pretty sure he wasn’t third. After some discussion, they realized Tim Shepard had actually finished third, so they took the trophy away from Palm, gave it to Shepard, and sent Palm to sit back down. But hey, it’s a low-key and quirky race, so I don’t think anyone minded. It was actually an admirable ceremony in at least two ways. It lasted all of five minutes–probably because the last runners didn’t finish till noon, and people had flights to catch. And they had a trophy for the DFL (Dead F***ing Last) finisher, Jacob Stevens in 51:48.

Would I recommend this race? Hell, yeah. It’s brutally hard and takes much longer than the typical 100-miler, but it is jaw-droppingly beautiful and the most social 100-miler I’ve done. The out-and-backs don’t seem redundant and offer a great opportunity to bond with other runners. The course is well marked, and for all my griping about the lack of vegan soups, the aid stations range from average (e.g., Richmond, Weehawken) to excellent (the much-trafficked Ironton and Fellin Park). The race is well-organized (when it counts), and every volunteer I met was friendly and helpful. There are hot springs to soak in afterwards. If you love mountains and aren’t afraid of a lot of vert, you should give it a try. Just give yourself some time to catch your post-race flight.

Will I do it again? Probably not. I’m happy with both my time and my experience, and I don’t think I can improve on either. I might feel differently if I were 32 or 45, but I’m not. I might also feel differently if it weren’t so hard, but it is. I feel lucky to have the buckle and some great memories, and maybe I don’t want to push my luck. But if you do Ouray and want a pacer, let me know. I’ll try to keep up.

One comment