What is Desolate Peaks? One could be forgiven for thinking it’s a race: it has aid stations, drop bags, timers, a course guide, and even a page on Ultrasignup. But races (and organized events more generally) are not allowed in the Desolation Wilderness, so it can’t be that. As the participant guide states–no less than six times–“THIS IS NOT AN OFFICIAL EVENT – JUST A GROUP OF FRIENDS ENJOYING THE MOUNTAINS.”

Whatever it’s not, Desolate Peaks is a remarkable opportunity to experience the Desolation Wilderness. The goal is to hit numerous Desolation peaks in one go–how many is up to you. The classic course (“The Beast”) consists of 17 peaks: Price, Agassiz, Pyramid, Cracked Crag, Keith’s Dome, Ralston, Talking Mountain, Becker, Flagpole, Echo, Angora, Cathedral, Tallac, no name 9579, Dick’s, Jack’s, and no name 9441. This will get you close to 20,000 feet of elevation gain in roughly 40 miles. For those who consider this a bit much–i.e., the sane–there’s an 11-peak “Fun Run” (the first 11 listed above). For those who think, like Lazarus Lake, that we could all use a bit more suffering, there’s a 21-peak “Beast + Lucifer’s Frolic” that adds four peaks in the northern end of the wilderness–South Maggie’s, North Maggie’s, Phipps, no name 9263–and which, prior to this year, no one had ever done. The map below shows the broad contours of the course: each waypoint is a peak, and the red line shows the approximate Beast route, beginning and ending near Wright’s Lake and followed in a counter-clockwise direction.

I say “approximate” because there is no set route: you just have to make it from one peak to the next. The participant guide says The Beast is 47 percent on trails, but I’d say this reflects a generous definition of “trail” as well as specific route-finding choices. One can often choose between a longer on-trail option and a shorter off-trail one, and different runners will make different choices. But all runners will spend the majority of their time off-trail, and much of that time figuring out where to go.

Desolate Peaks is (not) organized by Mats Jansson, who, along with some other spirited volunteers, provide the support runners need for such an attempt. There are two aid stations–at Echo Lake (mile 18) and Fallen Leaf Lake (mile 23)–where runners can leave drop bags. The non-organizers also provide shuttles from Echo and Fallen Leaf for runners who do the Fun Run or drop along the way. Two aid stations, five miles apart, in the middle of a 20-to-30 hour race isn’t much by normal mountain ultra standards. But it’s what makes an endeavor like this even thinkable to ordinary mortals like me.

I first learned of Desolate Peaks in 2021, and it seemed like my kind of non-event. I’ve loved Desolation for years, escaping there most summers to clear my head amidst its lakes and crags. I know the wilderness fairly well, even if I’d only summited four of the peaks, and I’m a moderately experienced rock climber–helpful on a course with more climbing than running. I signed up in 2021 but ultimately bailed due to that year’s fires. No such excuses this year: with good weather and smoke-free skies, it was time to get it done.

And yet. As the date approached, I felt a growing unease. Actually, let’s be honest: I was afraid. Not afraid I’d have a bad performance: I didn’t care about my time or place. Not afraid I’d DNF: if that happened, so be it. Not afraid it would be hard: I’ve done hard things. Afraid that something really bad could happen. Like, I could die. If that seems strange for someone who’s done a lot of backpacking and hard mountain ultras, I have to emphasize how different this was from anything I’d done. I’d traversed peaks like these, but always during the day. I’d spent many nights in Desolation and other wild places, but safely ensconced in my tent. I’d run or hiked through high mountain passes at night, but always on trails, and never too far from aid. The thought of navigating Desolation’s high, technical ridgelines in the dark, in the cold, perhaps with bad weather, possibly alone, scared me. Megan reminded me there’d be other runners in the race, including some I call friends. But we could get pretty spread out in a race this long, and I could easily end up on my own. That thought filled me with dread.

I was nervous enough to borrow Megan’s SPOT: a satellite tracking device that allowed me to send regular check-in messages to Megan and Mats, and an SOS to local rescue authorities if need be. It’s an old model that Megan bought for the PCT in 2016: it doesn’t allow two-way communication or typed messages, but it still works and allows pre-recorded messages with a link to your location. I set it up to say “Peak!” every time I sent a check-in, which I planned to do on every peak.

On race day, I arrived at the overflow parking lot at 5:25am. The main lot by the start was already full, so I parked here to wait for the shuttle. I saw a few familiar faces: Sam and his son Oliver, who were running together, and Shane, who helpfully got me a parking pass while I collected my gear. A few minutes later we caught the first shuttle to the start, where twenty runners milled around: four for the Fun Run, fourteen for The Beast, and two for The Beast + Lucifer’s Frolic. Someone greeted me, and it took me a second to recognize my friend Garret. “Dude, your beard is out of control!” I said–an inside joke, but also true. Mats called everyone to the start, offered some last-minute advice, took a group photo, and at 6:10am sent us on our way.

The group started surprisingly fast, running down the short paved road and along the flat trail leading to Twin Lakes. I settled into the back of the pack, thinking we had a long day and night ahead. After a short while we began to climb toward Mount Price, our first peak and the northernmost of the Crystal Range. I’d put together a tentative course GPX with information from the course guide, but with so many people ahead, I didn’t bother to look at my phone and instead mindlessly followed everyone else. It began to dawn on me, however, that we weren’t taking the route I’d planned: instead of continuing north past Twin Lakes and approaching Price from the northwest, we were heading east toward Smith Lake and approaching Price from the south. Oh well, that’s fine–I was happy to trust the wisdom of the crowds. (It should be noted that the lead runners missed a turn only a minute into the race, but most of the crowd didn’t follow them, which I’ll call a win for the crowd.)

Before long we left the trail and began climbing toward Price. This area was mostly slabs, large talus and scree, but not particularly technical. The sun cleared the ridgeline just as our route turned east, blinding me a bit. I hastily put on my sunglasses.

I soon caught up with Shane, and we traversed the first ridge together. It was an easy traverse, though maybe not comfortable for everyone, that provided a taste of things to come.

From there, it didn’t take long to reach Price. This was my first time on the north end of the Crystal Range, and it was worth the trip. To the south stretched the rest of the range: the sharp, hook-shaped Agassiz and behind it, at the south end, the aptly named Pyramid Peak. Far behind it and to the left, you could see the ridgeline stretching from Ralston to Talking Mountain to Becker Peak, and eventually to the eastern end of Lower Echo Lake, where we’d find our first drop bags.

Below and to the east was Lake Aloha and Desolation Valley, surrounded by the remaining peaks we’d do that day (and night). The photo below shows the peaks through Tallac. The last four–9579, Dick’s, Jack’s, 9441–aren’t shown because they weren’t that photogenic, and I wasn’t taking out my camera to catalogue peaks. But you get the picture: from here we could see the entire course, which was both uplifting and daunting.

Our route would be more circuitous than the above picture might suggest, as we wouldn’t simply move from right to left. After hitting Agassiz and Price and leaving the Crystal Range, we’d descend to and cross Desolation Valley to Cracked Crag. We’d then go Keith’s Dome, then to Ralston, then down the ridgeline to Talking Mountain, Becker, and Lower Echo Lake. From there, we’d move left across the landscape, hitting Flagpole, Echo, Angora and Cathedral enroute to Tallac. Then on to the remaining four peaks.

Shane and I moved on to Agassiz, which was easy. I stopped for a minute to put in eye drops: something I was supposed to do every hour, since I got Lasik surgery two weeks before. By the time I finished, Shane had disappeared. I continued on toward Pyramid but didn’t see him anywhere. Oh well–I’m sure he’d turn up eventually. My GPX guided me close to the ridge, but I remembered the course guide saying we needed to descend to the slabs below. I’d tried to follow those instructions when constructing the file, but without seeing the landscape before me, it was hard to know exactly what they meant. Now that I saw it, it seemed clear that I needed to descend further than I’d planned, so I did, cutting more or less straight across to Pyramid.

The route across the plateau was easy and even permitted some running. But at some point, I’d need to climb again. I wasn’t sure exactly where: the guide said to look for a steep and narrow gully, but that could mean a lot of things. I made my best guess and started climbing a promising-looking rock ledge. It was fine for a while, but got increasingly technical and eventually brought me to a steep cliff I couldn’t descend. I’d have to go back. I backtracked a bit, tried one descent, found that impossible, then backtracked some more and eventually got down to where some other runners were passing through. Having proved myself an inept route-finder, I decided to follow them. They soon located the aforementioned gully, and we took it up to the ridge. I remember this climb mostly for the wind, which was now howling. At the previous day’s check-in, someone had mentioned that we’d get sustained winds of 50mph on the ridges. That seemed about right: I climbed with one hand, using the other to hold my hat on my head.

It was a relief to emerge on the east face of Pyramid, which was shielded from the wind. The vibe suddenly changed: it was sunny and warm, and other runners were climbing to and descending from the summit. I’d been looking forward to this spot, as I wanted to check its reality against my memory. I’d been up here only once before, while hiking with a friend in 2012. We’d turned back before the summit, since the talus seemed dodgy, and that memory has stuck with me since. Now, however, it seemed fine. Sure, the talus would occasionally slide, but never far, and overall everything seemed solid. I hiked up to the top, took a few pics, and headed back down.

The descent to Desolation Valley was easy and quick, as was the trek across the valley. Lake Aloha was lower and drier than I’d ever seen, but maybe this is just how it is in late August–I’m usually here in June or July, when the snowmelt is still flowing. I crossed the Medley Lakes dam just north of American Lake, made my way to the Aloha Desolation trail, and followed that to the PCT.

I didn’t follow the PCT, but crossed it and immediately began climbing the talus toward Cracked Crag. I’d passed below Cracked Crag many times but had never bothered to ascend it. Doing so was fairly easy, if slow: just talus and more talus. Another runner–one of the few women out here today–caught up to me, and we chatted about how low the lake was. After seeing it full so many times, as in the pic below, it now seemed dull and sad. But again, that’s probably just the season.

Cracked Crag didn’t take long, and after taking a moment to put in eye drops, I headed back down. I’d planned to descend to the PCT but decided instead to take a shorter off-trail route. I’d have to depart from my original route at some point, as I wanted to stop at Lake Lucille for water, and the terrain didn’t look bad. In the end, it was probably a wash, as I traveled less distance but at a slower pace.

Lake Lucille wasn’t ideal for refilling, as the shores were reedy and marshy, and I wasn’t able to fill my filter flask. I eventually filled both of my drinking flasks, however, and continued on to Keith’s Dome. Like Cracked Crag, Keith’s Dome was straightforward: just a slow slog up the talus. I took a few pics, put in eye drops, sent my SPOT message, and headed down toward the PCT. It was now a little past noon, so I’d been going about six hours.

I hit the PCT exactly where I’d planned, at the junction with a small connector that led to Ralston Peak trail. This gave me the luxury of forgetting about navigation for a while: I’d simply follow the trails to Ralston Peak. I put away my phone, took out my poles, and made good time to Ralston. I’d summited Ralston so many times that I wasn’t much interested in taking pics, but here’s the obligatory view back toward the Crystal Range. To make it more interesting, I’ve indicated the four peaks that weren’t in my earlier pics, and which I’d (hopefully) be hitting sometime that night: 9579, Dick’s Peak, Jack’s Peak, and 9441.

The ridge toward Talking Mountain surprised me a bit. I’d imagined it as an easy, gentle descent, since that’s how it had always looked from Ralston. But it was slow going from the start, as it was mostly talus, and eventually became very technical, requiring hands-on climbing. I was constantly trying to decide whether I should stay on the ridge or descend to the talus, which dropped down steeply toward Cup Lake. I mostly stayed on the ridge, but that was not always smart. At one point I had no choice but to downclimb a steep crevice where a fall could have led to serious injury or, if I landed badly, death. It didn’t seem bad initially, but the holds turned out to be worse than expected, and I cursed myself for not backtracking and taking the talus route. It turned out ok, but I was rattled. The wind didn’t help: it was howling constantly, and I again wasted a hand holding onto my hat so it wouldn’t fly away. I’d tightened the hat’s headband as much as possible, but that was little use against a wind like this.

Shortly after leaving the most technical part of the ridge, I caught up with the woman I’d met on Cracked Crag, and then with Sam and Oliver, who I hadn’t seen since Pyramid Peak. They seemed to be doing well, and it was a relief to have some company for a while. I enjoyed the journey with them, first to Talking Mountain and then to Becker Peak. They lingered a while on Becker, but I was determined to cover as much ground as possible while it was still light, so I went on ahead. The remaining mile to Echo Lake was the easy, gentle descent I’d been hoping for, and I was in good spirits by the time I reached the aid station there.

Mats was there with another volunteer, who filled my hydration pack as I looked through my drop bag. I was grateful to them for being there: they weren’t making any money from this, and it was nice to see people willing to devote so much time and energy just so a few crazy people could have a great day on the trails. Mats said five others had already passed through, which surprised me: I’d thought there were more people ahead. But the last time I could see many runners was on Pyramid Peak, and there were a lot of miles between here and there, and many possible routes.

Sam, Oliver and their two companions arrived a few minutes later. I took my applesauce-filled flasks, a bag of potato chips, a bag of pretzel nuggets and few cookies from my drop bag and headed on my way. It was now a little after 3:00, so I’d been going nine hours.

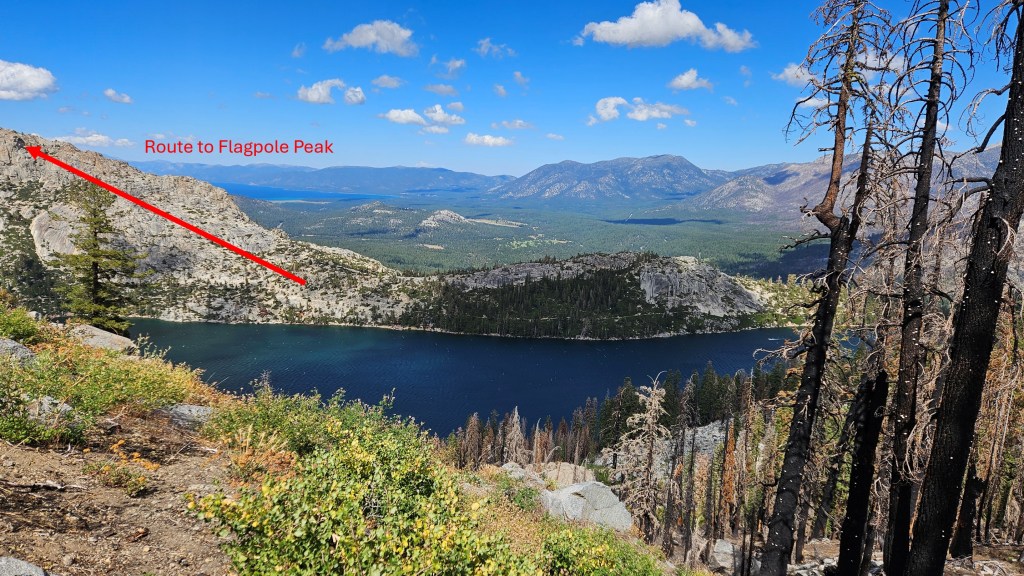

The first mile from the Echo Lake parking lot was easy, as it was on the PCT, and after eating my chips and pretzels, I ran for a bit. That didn’t last long, however, as I soon needed to climb to Flagpole Peak. I’d looked at those high rock slabs many times before but had never been up there. I didn’t think to take a pic, but this one from the ridge near Talking Mountain–across Echo Lake from Flagpole–shows the route to the peak, if not the peak itself.

As I climbed toward the peak, the wind got ferocious again. I took my hat off and stashed it in my pack’s chest straps, but then I realized that, while I’d re-applied sunscreen at Echo, I’d forgotten to put any on my forehead. I hadn’t bothered with that area because I figured the hat would protect me, but now I had to decide which was worse: dealing with the hat in the wind or getting sunburned. I put the hat back on, but I’d go back and forth for the next couple hours, depending on the wind.

The lower part of the ascent was steep hiking, but the higher parts involved hands-on climbing: not difficult, but slow. I enjoyed it, however, and felt like I was doing a better job route-finding now I was on my own. When you’re following others, as I was earlier in the day, you get lazy and stop paying attention–and that laziness can persist even after the others have gone, and get you into trouble. Now that I was conscious of being alone, I was taking more care: I’d try a route, decide I didn’t like it, and try another until I made my way through. I kept doing this until I saw the flagpole above me–yes, there’s a flagpole on Flagpole Peak. And there, wedged into a crack, was Shane.

I was surprised to see him. I’d last seen him on Pyramid Peak, where he was behind me. I didn’t know where he’d passed me, but he said he hadn’t stopped for water at Lake Lucille, so it was probably then. In any case, I was glad to see him. We left Flagpole and followed the ridge toward Echo Peak, moving as fast as we could. We both had the same idea: get as far as possible before the sun sets. We knew the night would be tough in various ways–cold temperatures spring to mind–but our biggest concern was route-finding. We had lights, of course, but those allowed you to see only a few dozen yards ahead, which was a big liability. You might follow a technical ridge that looks feasible only to find that it ends at an impassable chasm or cliff. And then you might find going back harder than going out. Other bad things could happen, but you get the point: it helps to be able to see. So we hurried on.

Right now everything seemed good. We were both feeling fine, and it was a beautiful day. The approach to Echo Peak was a wide, gentle plateau, and we even found a vestigial trail. I felt more relaxed than I’d been all day. The wind was still howling–I could barely hold my camera steady to take pictures–but that didn’t seem to matter in this safe, sunny place. We soon reached Echo Peak, which was unremarkable–which was fine with me.

The idyll didn’t last. As we moved north, the ridge got more technical. The course guide had warned us of this, but I didn’t remember anything except “If it seems like there is no way forward, back-track and try another approach.” We reached a scary gap in the ridge and debated how to cross. My first instinct was to stay high on the ridge and to take a narrow ledge to a point where you could hop across. That could work if you maintained your balance, but you could pretty easily die. Shane was meanwhile surveying the lower route, so I gave that a look. I found a narrow crack that you could climb to the other side, so I hiked down and climbed up that. It was tricky but doable, and safer than the other way. After reaching the top and rounding a corner, I was relieved to see the way forward looked safe.

After waiting a minute, I started to wonder what had happened to Shane. “You ok?” I called. He said he didn’t like the crack and was going to look for another route, maybe dropping down to the talus on the east side. Bummer. I’d have liked to stick together, but I wasn’t going to cross that gap in reverse, so I told him I was going to continue on. He’d caught me before; maybe he would again.

Angora Peak looked close, but the course guide noted (and my GPX showed) that the summit in front of me was a false one. I needed to get around it, but on which side: east or west? If I’d bothered to look at my GPX more closely, the answer would have been obvious: east. Not only was the slope on that side much more gradual; the map also indicated a trail to the summit. Somehow I failed to notice this and, because the west side didn’t require me to drop down, I went west. Big mistake. The west side consisted of a steep, sandy slope that was hard to not slide down without grabbing onto rocks–some of which came loose and tumbled down the hill. It didn’t feel deadly, but it was precarious, and it took a long time to get by. Eventually I made it through to the summit, where I took a few pics and sent another SPOT message. I exited on the east side, noting with chagrin how much easier it was than the west.

The descent from Angora was steep. Not scary–just a long, sandy slope–but steep enough that if you lost control and started sliding, you’d slide for a long time. I took out my poles to help stabilize myself. I hadn’t used them much today because I so often needed both hands, and they were at best a distraction on talus. But there were a few sections, like this, where they were helpful. I’d never been proficient at putting my poles in their quiver and taking them back out, but I got a lot of practice today and had already noticeably improved.

I soon reached the Angora Lake trail, which took me quickly to the Fallen Leaf aid station. It was pretty quiet there, with only one volunteer and a runner (Zoe Wood) who had just set the female course record for the Fun Run. The volunteer told me two other runners had continued on: so now we were down to two. Not that it mattered: I just wanted to finish. It was now around 6:30, so I’d been going around twelve and a half hours.

I filled a flask with water, drank it, filled it again and drank it again. I was planning to cut straight from Tallac to No Name 9579, bypassing Gilmore Lake and the PCT. This would shorten my route, but I’d have no chance to refill water until the Rubicon River, beyond Jack’s Peak. I probably wouldn’t need much water in the cold, but I didn’t want to take chances, so I hydrated well here and then filled both flasks with Gatorade. I then turned to my drop bag. I took out my Primaloft (synthetic down) jacket and put it in my pack, along with another Lenny’s and Larry’s cookie and spare batteries for both my light belt and headlamp. Then I grabbed what I’d really been looking forward to: two ziploc bags of ramen noodles. I’d cooked them beforehand and mixed them with the flavor packets, making them nice and salty and giving me 1100 calories. I knew there was a long, flat road to the Cathedral trail–my chosen route to Cathedral Peak–and I planned to walk that road leisurely, eating the noodles on the way. My reward for what I’d been through, and what was to come.

I said goodbye to the volunteer and Zoe and walked away eating my noodles. I got maybe a quarter-mile before I realized: I’d planned to leave my hat and sunglasses in my drop bag, as they were taking up space and were no longer needed. I turned around and walked back, greeting Zoe and the volunteer again, then headed back out. This time I got as far as the Stanford Sierra camp before I realized: shit, I forgot my warm gloves. I’d come closer to a half-mile this time, so I briefly contemplated continuing without them before concluding that was insane. Cursing myself for being so careless, I headed back to Fallen Leaf. I felt sheepish showing up there again, but whatever–I needed the gloves. I grabbed them and left for the third and final time.

The delay wasn’t all bad. Maybe it would give Shane time to catch up, and it gave me time to eat both bags of noodles. They were satisfying and would hold me quite a while. I chased them with my first 100mg of caffeine: the sun was setting and I wanted to stay alert.

I hadn’t seen the Stanford Sierra Camp since I was an undergrad back in 1991, and didn’t remember much besides canoeing on Fallen Leaf Lake and losing a lot of money at a South Lake Tahoe casino. It didn’t ring any bells now. I passed through the camp to a parking lot where the Cathedral trail began, and took the trail.

This was a long and circuitous way to reach Cathedral Peak. There was a much shorter route: a steeper trail right below the peak–which Megan and I had discovered last summer–followed by an off-trail scramble up the hillside. Sam had said he planned to take that route, but I chose the longer and more gradual one both so I could eat my noodles and because I could use a break from steep, technical stuff. As I hiked up the gentle slope, I didn’t regret my choice. It was nice to be on an actual trail, to stop looking at my phone, and to use my poles. And the trail provided great views of Fallen Leaf Lake and Tahoe in the setting sun.

The trail wound slowly upward. The sun went down, and the moon came out. I reached Cathedral Lake and decided to drink a flask and refill it, just to be safe. It got colder and windier as I climbed, so I stopped to put on my rain jacket. I left the forest for more talus and got a nice view of the moon behind Cathedral Peak.

The wind was really howling now, and this caused problems for my hood. I’d put the jacket hood on to keep my head warm, but the wind kept whipping it around. I tightened the straps, but the fasteners couldn’t stand up to the wind. I tried tying the straps but gave up, figuring I might not be able to get them untied. It occurred to me that I’d prepared poorly and should have brought better gear.

Aside from the wind, the ascent was fine. It was still nice to be on a trail and I was in no hurry to leave. I liked the trail so much, in fact, that I lost track of distance and hiked past the point where I’d planned to cut across to the plateau leading to Cathedral Peak. No harm done, though: I could cut across here. I left the trail and navigated a long stretch of talus to the plateau.

Once I reached the plateau, getting to Cathedral Peak would be straightforward: I’d head out to its terminus, where the peak was located, and come back. In practice, however, this turned out to be harder than I’d thought. For one thing, the plateau was technical in places: mostly talus, but I also blundered into a few spots that required more care. I realized my light belt was useless for anything resembling a climb: when your body was twisting this way and that, you couldn’t point the light where it needed to go. I put on my headlamp: better. The headlamp also held my hood in place, solving that problem.

The larger problem was that I couldn’t maintain my direction in the dark. The route to Cathedral Peak should have been a straight out-and-back, but I found myself constantly wandering off course. I’d come up to the edge of the plateau, realize there was a big drop, then pull out my phone to reorient myself. Eventually I decided to just keep the phone out and watch it constantly as I walked along.

I reached the peak, sent my SPOT message, and turned back. The way back went a bit more smoothly, as I stayed glued to my phone. (I really should have loaded the GPX into my watch. I didn’t because I generally prefer my phone, but I usually don’t have to check it often. Lesson learned.) When I reached a sheltered spot in the woods, I stopped to put on my Primaloft jacket and gloves. Better here than in some windy spot above, even if it meant being hot on the hike up to Tallac.

I located the Floating Island trail, which led all the way up to Tallac. The sky was dark, but I could just make out Tallac’s silhouette looming above. I had a good stretch here: I was able to put away the phone and take out my poles, and the continuous hiking warmed me up. I ate some pretzel nuggets and took another caffeine pill, and was feeling good by the time I reached the short connector trail to the summit.

I couldn’t see much, but I knew Tallac well enough to be aware of the steep drops all around. Fortunately, the route is easy and safe, and I navigated the talus and rock formations to the top. It was now just past 10:00pm, so I’d been out here sixteen hours. I sent my SPOT message and headed down. As I did so, I saw lights in the distance below. “SHANE!” I shouted, hoping it was him. But then I noticed there were two lights, so maybe Sam and Oliver? I thought the lights might have moved when I shouted, but maybe not. In any case, they were a long way off, so I continued on.

I soon reached the point where I had to choose between two routes: the trail down to Gilmore Lake and the PCT, or an off-trail shortcut straight across to No Name 9579. The trail offered water and, well, a trail, but the shortcut eliminated two miles and a thousand feet of elevation change. I’d planned on the shortcut and had put together a GPX for this purpose. I headed off trail into some tall grass.

I found the off-trail hiking pretty pleasant: mostly tall grass, with some occasional pushing through pine groves. I checked my phone frequently but not constantly. Suddenly, however, I found myself looking down into a chasm: I’d almost walked off a cliff. What had been a wide plateau had narrowed into a ridge with steep drops on both sides. Hiking the ridge was neither technical nor hard, but you did need to know where to go. I was glad I’d put together the GPX and kept my eyes on my phone from then on.

Speaking of eyes: this ridge was littered with the pine trees I’d seen all day, which sported some really sharp needles. As I pushed my way through a grove, a needle stabbed me in my left eye. This would have been painful under any circumstances, but my mind immediately went to my Lasik. It had only been two weeks since my surgery, and my eyes were still healing. I’d been so careful to take care of them, using my antibiotic, anti-inflammatory and lubricating drops on a set schedule, and following the doctor’s instructions not to rub them for a month. And now I stab myself in the eye? The eye felt irritated and watered a lot, and I worried I’d done some irreparable harm. But I could still see, and there was nothing I could do about it now, so I hoped for the best and pushed on.

I reached 9579 easily enough. I couldn’t see anything, but I knew where I was, having passed by many times on the PCT. This summit was a small rounded hill just above Dick’s pass, and would have been comfortable if not for the wind. I crouched down behind a rock and sent my SPOT message. I was sending those messages to let Megan know I was ok, and to give Mats a record of my peaks, but I’d also come to value the implied connection with the outside world. Even though the transmission was only one way, it somehow made me feel less alone.

I headed down the hill to the PCT, then took the trail leading to Dick’s Peak. I couldn’t see much in the dark, or take any pictures, but here’s one I took of Dick’s and Jack’s a while back, with Half Moon Lake down below.

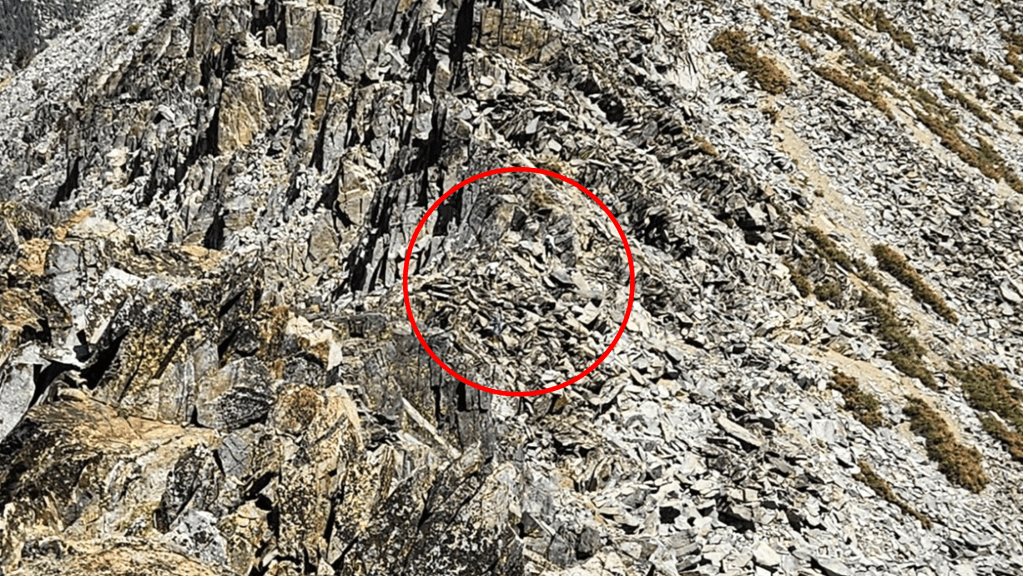

And here’s a fragment of another picture I took, which caught Dick’s in the background. It’s grainy because I had to blow it up, but it clearly shows the spine that constitutes the main approach to the peak.

Needless to say, this isn’t what I saw in the dark. I could barely make out the peak’s silhouette, looking huge and menacing. I’d remembered the approach as a gentle ridge, and that was true for a while. But the ridge got steeper and steeper, and eventually the trail disappeared into rock faces you had to climb. Most of this was not bad: you had to use your hands, but you’d be fine if you kept your wits about you. But one section, maybe 15 feet high, gave me serious pause. It wasn’t vertical, but it was really steep, and the hand and footholds weren’t great. The slopes below it were so steep that if you slipped and fell, you’d probably keep on falling, probably until you died. I might have had a different take in the light of day, but there, in the dark, freezing in 50mph winds, climbing this face seemed insane.

I felt trapped and hopeless. I really didn’t want to climb this face, but I didn’t see any alternative. There was no nearby aid station where I could drop, and I felt like I’d reached a point of no return. What was I doing out here, anyway? Why did I think this was a good idea? I didn’t want to die. I closed my eyes for a second and took a deep breath. “The only way out is through,” I thought. (I know, it’s a cliché, but cut me some slack–I wasn’t at my best.) I was just going to have to make this work. I made a mental note to stay calm and focused, and began to climb.

A few seconds later, I’d cleared that part and was back on firmer ground. It was still hands-on climbing, but the hand and footholds were good. Crisis passed. I continued up.

(Note: At the base of that climb, I actually wasn’t at a point of no return. I could have walked back to the PCT and then taken trails all the way back to Fallen Leaf. It would have been a long journey but a safe one. However, once you’ve done that climb, you are basically committed. Downclimbing Dick’s in the dark would be a very bad idea, so once you’ve climbed it, you have little choice but to continue on to Jack’s. From there the return would be very long, as you’d have to descend to Mosquito Pass and make your way back from there.)

(2025 update: Having done this race again in 2025, I can now say that last year’s frightening experience on Dick’s was the result of bad route finding. This year I managed to stay on the standard route to the summit, which was comfortable and safe. So, in 2024 I somehow blundered off course into a needlessly technical ascent. I’m not sure why this happened, as the standard route seemed pretty obvious this year, but I’m guessing it had something to do with feeling rushed in the wind. In any case, Dick’s turns out to be an easy climb if you take the correct route.)

A few minutes later, my light belt began to flicker, letting me know the batteries would soon die. That didn’t matter much right here, since the belt didn’t shine in a useful direction (i.e., above) anyway. But my headlamp batteries were also almost dead, and its light was very dim. I jammed myself into a crevice where I had some shelter from the wind and changed both sets of batteries. Better.

Not long after that, I really started to worry about the cold. I’d been shivering for some time, and it was getting worse as I climbed higher and the wind got more intense. The temperatures were supposed to be in the high 30s or low 40s, but with the wind chill it felt much colder. I was wearing shorts but had no pants, and while I had my Primaloft jacket, the rain jacket over it was very light and not windproof. Worst of all, I was moving so slowly up this rock that I wasn’t generating much body heat–my usual defense against the cold. I had to do something.

I had an emergency blanket in my pack, and it occurred to me that I could wrap it around my torso and put my jacket on over it. I found another sheltered crevice where I could give this a try. I pulled out the foil blanket and began to unfold it. To my dismay, it came apart at the creases, and I was left with not a blanket but a bunch of foil ribbons. WTF?? I guess emergency blankets don’t last forever. This one had been in my closet for years–part of a value pack–and had clearly degraded over time. I bunched the ribbons together as best I could, took off my rain jacket, and tried to wrap the ribbons around my torso. It didn’t work that well–they were flying everywhere in the wind–but I at least managed to encircle my rib cage. Good enough: I put the rain jacket back on, then strapped on my pack to hold everything in place. It wasn’t the solution I’d hoped for, but it did make a difference. I could already feel the ribbons trapping a bit more heat. Maybe I wouldn’t die after all.

I looked back the way I’d come and noticed lights in the distance, maybe near the PCT. I guessed it was the same people I’d seen from Tallac, probably Sam and Oliver. They seemed farther behind now, but it was hard to tell. They’d certainly take a long time to get here, longer than I could wait.

A bit more climbing brought me to the summit. The wind was so ferocious that I couldn’t stand: when I tried, I got knocked off my feet and almost off the mountain. I got down on all fours and crawled to the highest point. Someone had built a stone circle up here, maybe 18 inches high, and I lay down inside the circle to escape the wind. I pulled out the SPOT and sent a notification. I thought about Megan on the other end and wondered how she imagined this to be. Did she suspect it was like this? Or did she imagine me strolling comfortably along a ridge? Was she even awake? It was now almost 1:00am, well past her bedtime, and I’d been out here almost 19 hours.

I headed down the ridge toward Jack’s Peak. I don’t remember this part very well, but the climb to Jack’s was definitely less stressful than the climb to Dick’s. It required hands, but the climbing was easy and safe, and I reached the top without any scares. It was still crazy windy and cold, however, so after sending my SPOT at 1:50am, I quickly headed down.

The descent from Jack’s sucked. It wasn’t really technical, just a super steep hill where your options were loose sand or talus. I initially went back and forth: the talus was less likely to slide, but occasionally a big rock would start to roll and keep on rolling. I heard one of them crashing down the hill long after it disappeared from sight. Thinking about Dave Mackey and Aron Ralston–both of whom had had limbs crushed by rocks–I decided the sand was the safer bet.

The main problem with this descent was that it was really, really long. It just kept going…and going…and going. I initially tried to stay on the course I’d plotted, but I concluded that holding my phone was a bad idea. It wasn’t that I needed my hands, but that I was constantly falling and using my hands to break my fall. If there was one thing I couldn’t allow, it was damage to my phone. Without it, I was effectively blind and couldn’t go on. So I decided to forget about the route and just get to the bottom.

All routes led to the same place, anyway: the Rubicon trail. Once I reached it, wherever that was, I could make my way to where I’d planned to cross it and go up the other side. So I just kept going down, not worrying about my direction. Eventually the grade moderated a bit, the vegetation grew thicker, and the wind died down. I sat down next to a tree and tried to eat a cookie. It was hard and frozen, but I managed to get half of it down. Then I continued toward the trail.

Things got a bit weird here. I reached a flattish area, checked my location relative to the route I’d plotted, and headed off in that direction. I was south of my route, so I headed north. But after walking a while, I checked my phone again and found I’d moved even farther from my route. Somehow I’d been heading south toward Mosquito Pass. I didn’t understand this: I thought I knew where Jack’s was behind me, and that told me the direction I needed to go. I began to distrust my phone, thinking it couldn’t be right. The truth, however, is that I was starting to lose it mentally: between fatigue and the dark, my sense of direction was shot. I had enough sense left to do the smart thing, i.e., I trusted my phone.

I soon hit the trail, took that back to my GPX route, then left the trail and headed to the Rubicon River. The river was low, and I quickly found some logs on which I could cross. Then I headed up the other side to the last peak. At first this seemed like a relatively easy ascent: the valley wall consisted of huge rock slabs that were easy to walk on. But after a while things got tougher. The way up was impassable in many places due to either rocks or vegetation. I mostly followed my GPX, but that route was just a best guess, and it often ran me into those impassable spots. I was gradually climbing, but at a snail’s pace, as I searched for the spots that would let me through.

My brain was doing weird things. I’ve long had an earworm problem during long ultras. Whatever song or songs I last heard keep playing in my head on an infinite loop. During Bighorn in 2022, I was plagued by the Encanto soundtrack because I’d just seen the film. This time the culprit was an Economist article on Pennsylvania politics. The article mentioned the Billy Joel song “Allentown”–which is, I think, a pretty good Rust Belt ballad–which led me to listen to that and some of his other songs. They’d now been cycling through my head for hours. I was sick of it, but maybe anything that passed the time was good. And “Pressure” did at least capture the vibe:

You’ve only had to run so far, so good

But you will come to a place

Where the only thing you feel

Are loaded guns in your face

And you’ll have to deal

With pressure

I also found myself visualizing scenes from the BBC series All Creatures Great and Small. I’d recently listened to the books by James Herriot and thought I’d check out the show. I don’t love it–too saccharine for even my taste–but now my mind kept wandering to images of the Yorkshire Dales. I suppose it was an escape, those comforting green hills a refuge from my current plight. And maybe that too was good.

I finally broke through the rocks and vegetation to a steep and arid moonscape. I could hike unobstructedly here, although the hiking was slow because the sand kept sliding under my feet. I stopped to check my phone and was surprised to see that I was almost there. I could now see beyond the ridge; on the other side was an extraordinary red moon.

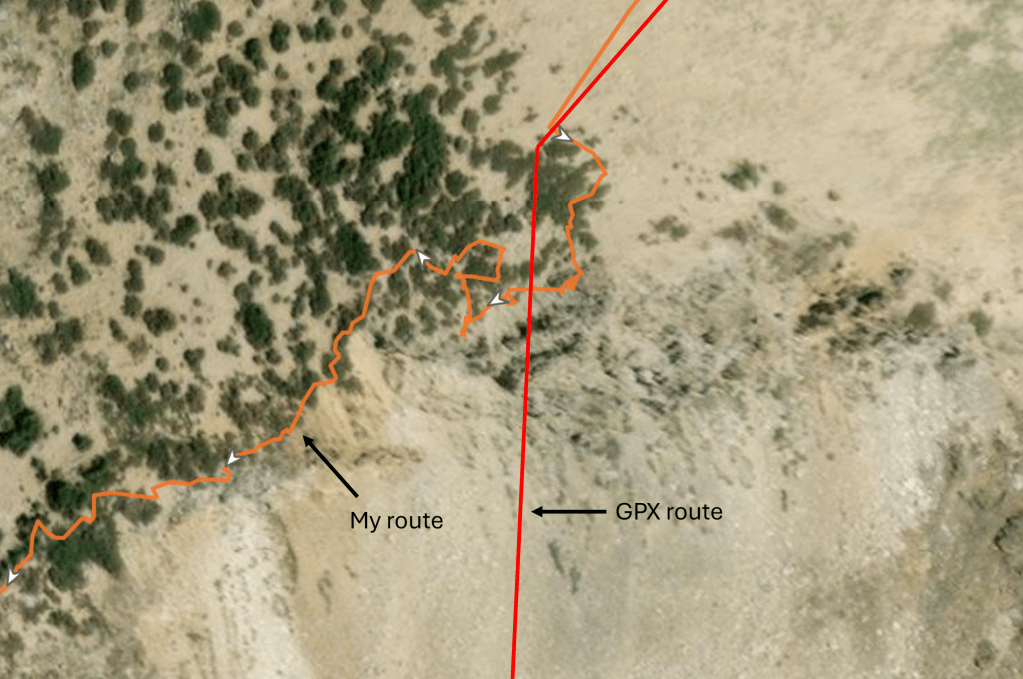

A few more strides brought me to the summit. I sent my SPOT message–my last, a little after 4:00am–and looked for the route down. I initially tried to follow my GPX but was dismayed to find that it led me over a cliff. I looked for another way and began to descend, but that too vanished over a cliff and into a black void. I scrambled back up. This picture shows my GPX route (red) and my attempts to find another way (orange).

What the picture doesn’t show is my rising sense of panic. I had no idea how to get down. In retrospect, it shouldn’t have been hard: I had Gaia, and that told me where the finish was. I just had to use the topo map to find a gradual descent, and I’d be fine. But that’s easy to say now. At the time, my mind was frayed. After getting lost near the Rubicon trail, I’d stopped trusting both myself and my phone’s directional arrow. I’m sure the latter was fine, but nothing made sense to me. Those lights on the horizon in the moonset picture above–what were they? South Lake Tahoe? Reno? The Central Valley? I had no idea. (For the record, it’s the Central Valley.) I was completely disoriented and, even when looking at my map, couldn’t make sense of it. To make matters worse, I could barely see the real world: my light belt was fine, but the headlamp was almost dead, and I had no more batteries. And the wind… For hours, my emotional state had followed the wind. Whenever it fell for even a minute, I felt a palpable sense of calm. Now it was howling in my ears, and I couldn’t think straight. I needed shelter.

I crouched down behind some shrubby trees and took a good long look at my phone. With my mind calming a bit, things didn’t look so bad. The topo map clearly indicated a gradual slope that would take me down to the Twin Lakes area. I headed off in that direction, always looking for the easiest route. That never ended up being the route I’d plotted, but once I’d gotten past those initial steep cliffs, I was able to stay fairly close to my GPX. The wind died down as I descended, and soon I felt safe.

As I approached Twin Lakes, it began to get light. I found this dismaying at the time: a sign of how long I’d been out there. It took me longer to grasp the bigger implication: the sun was always going to rise! I’d spent half the night fearing I’d get lost and freeze to death. But that was never likely: morning would eventually come; temperatures would rise, and I’d have light to navigate by. Somehow I’d forgotten this truth, believing the night and cold and wind to be eternal, the finish line the only escape. As I said, I wasn’t all there.

The rest is simple. I reached the Twin Lakes trail and made my way slowly to the finish, taking a couple of wrong turns along the way. I saw several guys standing at the finish: Mats, Shane and two I didn’t know. They clapped for me and I wearily said “Thanks.” And then I was done. I was confused, thinking for some reason that one of these guys was Oliver. Where was Sam? And how was Shane here? Had he passed me when I was meandering around Rubicon or up that last peak? Turns out he’d dropped after Cathedral Peak due to watch problems, and gotten a ride from Fallen Leaf back to his car. That was good news for me: my car was parked nearly a mile away, so I was happy Shane’s was here now. I was having trouble talking, much less walking.

We chatted with Mats for a bit and learned about the history of the race, which had grown organically from a few guys bagging peaks to what it is today. Mats gave me a finisher’s beer: a fine helles lager. Shane drove me back to my car and I drove home, stopping four times along the way to close my eyes. I was wrecked.

It was a good year for Desolate Peaks: as Mats said, a year of firsts. Josh Cleveland set a new course record for The Beast, finishing in 20:51. I was second in 24:46 and was, at 55, the oldest Beast finisher ever. Eighteen-year-old Oliver, who finished third with Sam in 27:07, became the youngest Beast finisher ever. Melody Hazi–who, it turns out, was the woman I’d met around Cracked Crag and Talking Mountain–became the first female ever to finish The Beast, in 28:11. Zoe Wood set a female record for the Fun Run of 12:01. Most impressively of all, AJ Kaufmann became the first person ever to finish The Beast + Lucifer’s Frolic, in 29:03. Of the fourteen people who’d set out to conquer The Beast, six had finished. Which, when you think about it, is pretty good.

Would I do it again? It partly depends on what “it” is. I would absolutely do the Fun Run again. Those first eleven peaks are spectacular, and I loved doing them under the sun. Anyone who wants to see Desolation in all its glory should give it a try. As for The Beast: I don’t know. I suspect my pre-race apprehension was trying to tell me something important. Maybe something like this:

Seriously, it was really hard. Not the physical strain–I’ve put my body through worse–but the cold, wind and technical route-finding at night really stressed me out. That said, these problems can be solved. Better clothing would deal with the cold and wind. Reconnoitering the night parts beforehand would make me more comfortable on Dick’s Peak and faster on 9441. And I could get to the night parts faster–and do more during the day–simply by having done the course. (I wouldn’t, for example, waste time getting stuck on that ridge beneath Pyramid Peak.) So I could imagine doing it again, if I made the time to prep. Whether I’ll do that, I don’t know. But I’m glad I did it once. And I’m glad someone is (not) organizing something like this, so others can give it a try. Because man, those are some peaks.

2 comments