Note: I’m writing this in July 2024, ten months after the race, so some details are fuzzy. But be warned: there are still a lot of details.

If you’d told me ten years ago that I’d end up doing a multi-day 350k race through the Alps, I might have asked “Why?” I’d always been better at shorter, faster races, and back then even runnable 100-milers seemed like a stretch. But it turns out we don’t get faster with age–at least on my side of the curve–and when your PR days are behind you, you start looking for new challenges. Like fast-hiking for days through the mountains on almost no sleep.

Even so, I wouldn’t have entered the Tor had Megan not applied for the Tor de Lucas scholarship. Named after Lucas Horan, a Bay Area adventurer who loved the Tor–but who died tragically in 2020–the scholarship pays race, travel and coaching expenses for one athlete who most embodies the “spirit of Lucas.” In 2023, Megan was that athlete. And if she was doing this alpine adventure, I wanted to come along.

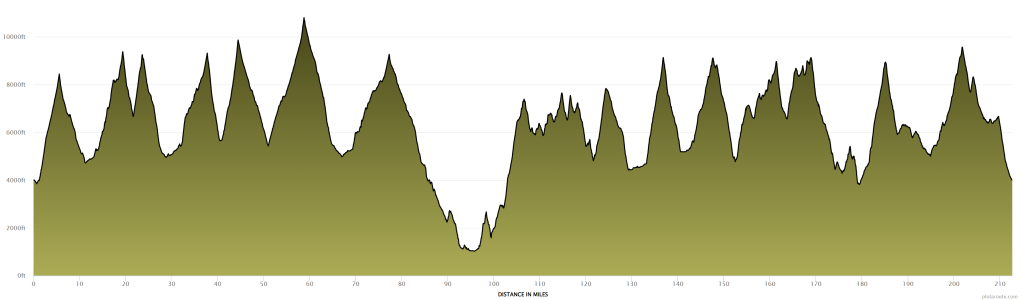

For those not familiar with the Tor des Geants (“Tour of Giants”), it’s a long race around Italy’s Aosta Valley. Exactly how long is somewhat unclear: it’s called the Tor 330, but most GPS watches put it closer to 350k (220 miles), and the race’s GPX file says 343k (213 miles). Whatever; it’s long. It’s also hilly–I mean, it’s the Alps–with over 80,000′ of elevation gain. Until recently it was considered one of the hardest ultras in the world, along with other such worthies as Badwater, Barkley, and Marathon des Sables. This may be less true today, thanks to never-ending race inflation: TorX now offers the 450k Tor des Glaciers; SwissPeaks has a 660k, etc. I’m not sure where this all ends, but 220 miles of crazy steep mountains still seems long to me.

Although both of us had done long races, the Tor would be qualitatively different and would present some unfamiliar challenges. One was sleep. Unlike a 100-miler, you can’t do the whole thing in one sleepless shot. But unlike some multi-day events, the Tor is not a stage race, i.e., the clock never stops. Sleep along the way adds to your time, so you have to strike the right balance between necessary rest and excessive delay. Since we’d never slept during a race before, we had no idea how much sleep we’d need, how often we’d need it, etc. Friends who’d done the race had slept very little: e.g., five hours in five days. That seemed extreme to us–we both leaned toward getting a bit more sleep and feeling a bit better–but we realized we’d have to play it by ear. We definitely planned to run through the first night without sleep; after that we’d have to see.

Another challenge was pacing. We both wanted to run the race together, for moral support and English-speaking company. Moreover, I’d signed up mostly to support Megan (and see some amazing stuff), so running with her was always my default plan. However, Megan’s coach advised against sticking together rigidly, and that also made sense. Megan and I are different runners, and even when we run the same average pace, we usually alternate leads and lags. Sticking together could lead to a lowest-common-denominator pace that would slow us both down. Our uncertainty about sleep complicated things further, as we might want to sleep at different times or for different durations. In the end, we decided on a middle course: we’d try to stay within catching-up distance of each other without being together the whole time. Hopefully this would give us some flexibility while still allowing us to see each other along the way.

A final challenge was deciding what to bring into the race. The Tor gives each runner a “follow bag” that runners can fill with whatever they want: food, clothing, gear, etc. These bags can be accessed at each “lifebase”: the major aid stations, located roughly every 50k, where runners can sleep, shower, and get more substantial meals. While it’s nice to have this resource, it raises a lot of questions about what to bring. Microspikes in case of snow? An extra set of poles? Plug-in chargers or just battery packs? It’s always tempting to overprepare, but the follow bags only hold so much–and as I would learn, you don’t necessarily want to bring everything they can hold.

As for training: I felt pretty good going in, having done Western States in June and the Beaverhead 100k in July. Both of those races are quite runnable, however, and not ideal prep for the steep hikes of the Tor. So we spent August hiking up and down the steepest hillsides we could find. That mostly meant three fire trails on Mt Tam: East Peak, Indian, and Lagunitas. All three trails go straight to the summit with no switchbacks, offering over 1,000 highly technical feet of elevation gain per mile. We got to know these trails really well.

We left for Europe on Sunday, September 3. Packing was a challenge, as I was committed to bringing only a carry-on but had a long gear list: two pairs of shoes/socks/shorts/shirts, two pairs of trekking poles (in case one broke), hydration pack, cold-weather gear (down jacket, thermal shirt, hat, gloves, tights), rain gear (rain jacket, rain pants), light belt and batteries, battery pack for charging on the go, etc. I somehow managed to fit it all in, but I had to abandon two types of fuel I really wanted to have: Gatorade Endurance Formula, which is the only sports drink I like, and protein bars, which I figured would be good for a vegetarian to have on a multi-day race. Oh well: I’d just have to buy something similar over there.

We arrived in Geneva on Monday, September 4 and spent a couple of nights there. This was my first time seeing Geneva, and I was impressed. It’s not an architectural gem like Prague or Venice, but it seems very livable. Our Airbnb’s neighborhood was a bit red-lighty but boasted an incredible diversity of restaurants: every cuisine imaginable within a few blocks. On Tuesday we went for a short run along the waterfront and through the old town, then went swimming and got dinner with Megan’s trail friend Noemie and her kids.

On Wednesday, September 6 we picked up our rental car and drove to Chamonix. We hadn’t originally planned on a car, but there was ongoing uncertainty surrounding the Mont Blanc tunnel, which connects Chamonix to the race start in Courmayeur. Shortly after we’d bought our tickets to Geneva, we learned that the tunnel would be closed for construction. This threw a monkey wrench into our plans, as all public transport to Courmayeur went through the tunnel–and was not rerouted. As we landed in Geneva, the tunnel’s status was still unclear: the closure had been postponed, but French and Italian authorities continued to debate how long. Renting a car–which would allow us, if needed, to make the long drive around Mont Blanc–seemed like the safe option, so we sucked up the cost and drove.

This was our first time in Chamonix, which–thanks to the prominence of Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc (UTMB)–has become something of an ultrarunning Mecca. It was amazing. The snow-covered Mont Blanc massif is a constant, looming presence. You can’t look up without seeing paragliders circling high above. The town itself is beautiful, and at one point Megan remarked that it’s basically Disneyland for trail runners (and other outdoor athletes). True enough: I don’t think I’ve ever seen another town so totally devoted to outdoor sports. When we boarded a local train for a short point-to-point run, we were, for a change, not the only passengers in running gear and hydration packs.

While in Chamonix, we did some shopping for things we couldn’t fit in our carry-ons. Those things proved surprisingly hard to find. Protein bars were easy enough, but I searched in vain for a sports drink that looked good. Most were too weak for my liking–I don’t see the point in filling a flask with 80 watered-down calories (Gatorade Endurance Formula has 180)–but I finally settled on an unfamiliar sports drink, in assorted flavors, that contained, among other things, milk solids. I also looked for a foam roller, which I thought might be good to have in my follow bag. I couldn’t find any foam ones–just unpleasantly hard, rubber-sheathed plastic cylinders–but that’s what they had, so I got one.

Also hard to find: sunscreen. Megan and I combed multiple stores, but all we could find was some very low-SPF stuff for kids. A weird dilemma in a highly commercialized outdoor-sports destination, but we figured shops had run down their summer inventories after UTMB. We decided we’d have better luck in Courmayeur.

On Friday, September 8 we headed to Courmayeur. The tunnel was open, but the traffic was horrendous, and the 14-mile trip took almost three hours. We checked into our Airbnb and headed into the town center to orient ourselves. We went first to the race headquarters at the Courmayeur Sports Center, then shopped for groceries–learning that kale is not a thing here–and finally parked near the center and walked around. Courmayeur is small but lovely, with one main pedestrian street, the Via Roma, running through town. The center was already bustling with race activity, as the Tor des Glaciers was about to start. Tor posters and banners were everywhere, adding to the pre-race electricity. We particularly liked the official poster and wondered if we could bring one home:

On Saturday, September 9 we headed back to the Sports Center for check-in. At the entrance we ran into an acquaintance, Shane, who seemed to keep popping up in unlikely places. We’d met on a post-race train after the 2022 SwissPeaks, and while I don’t know the odds of meeting another San Rafael resident on a train in rural Switzerland, they seem long. Then, over the summer, we ran into him on the Indian fire trail–itself not a place where one runs into people–and learned that he was also doing the Tor. He’d arrived here before us and explained the check-in process. We’d have to get a ticket, then wait until our number was called. This looked to take hours, but at least we could keep tabs on the ticket queue with a mobile app. We went inside and saw Maureen, the previous year’s Tor de Lucas recipient, at the massage tables. After saying hi to her, we grabbed our tickets and left.

On our way out we ran into Mat, Maureen’s husband and another Bay Area runner. I asked if he had any thoughts on where we could leave our car. This had been on my mind, as we’d need to leave it somewhere while on the trail, and I didn’t want to return to find it towed. After some discussion, we decided it would be best to leave it where it currently was, in the Sports Center parking lot. We’d have to do without it until after the race, but at least we’d know it was safely parked. We walked the mile or so back to our Airbnb, grabbed all the things we thought we’d want in our follow bags, and brought them back to the car so we could pack them later.

We whiled away the remaining hours by exploring the town center. It was a beautiful day, and relaxing to walk around. We checked out some shops–eventually finding some overpriced sunscreen–took in some live music on the main town square, located the race start, and generally basked in the sight of the surrounding peaks. At some point we ran into Mat again, along with Jan Horan (Lucas’s mom), who’d helped establish the Tor de Lucas scholarship. We knew she’d be around, as she had been the last few years, and were glad to finally meet her. After chatting for a while, we went back to our Airbnb to rest and wait for our number to be called.

By late afternoon we’d neared the head of the queue, so we walked back to the Sports Center and checked in. The process seemed a little chaotic–a lot of people jumping the queue–but we got through quickly enough, received our follow bags, and were soon back at the car packing them. It occurred to me that I might be taking too much: the foam roller, extra shoes, extra poles, change of clothes, battery pack, plug-in battery charger, myriad types of food, etc. all took up a lot of space. I eventually fit it all, but it was an engineering challenge, and would continue to be.

By happy coincidence, Jan drove into the parking lot as we were packing and gave us a ride back to our Airbnb. She also offered to drive us back to our car in the morning so we could leave our luggage there–an offer we gratefully accepted, as it would spare us a long walk with our backpacks on race morning.

The next morning–Sunday, September 10–Jan drove us to our car, then to the town center. We had some time to kill, so we went in search of food. I bought some apple fritters from a bakery and ate them as we walked to the start. The streets were crowded with runners and spectators, and we felt nervous about the journey we were about to begin. A race like this was terra incognita to us, and we had no idea how it would go.

The starting chute was crowded, and since we didn’t care about our starting position in a race this long, we settled in mid-pack along with Shane. We chatted with some race veterans, including one guy who was here for the seventh time. I found that comforting: this couldn’t be that hard if people do it again and again, right?

A few more minutes of waiting, a quick countdown, and we were off. The start was crazy: 1,200 runners crowding the narrow Via Roma, with music blaring and crowds cheering. Still one of the most memorable moments of my race.

Once we left the Via Roma, the streets opened up and we ran at what seemed a pretty fast pace for a race that would last days. I soon wished I’d started faster, however, as the first bottleneck–a steep single-track into the woods–brought us all to a standstill. We had to wait quite a while just to get on the trail. After that, the miles were slow: 25 minutes, 36 minutes, 21 minutes, 29 minutes, 22 minutes. This was partly because the climb was steep–almost 5,000′ of gain in the next five miles–but also because the bumper-to-bumper traffic made passing impossible. I was mostly fine with this, for now: although I looked forward to breaking free, we were just getting started, and the views were spectacular. There were also some unexpected treats, like bulls tussling on the trail.

About six miles in, we finally crested the first col (Col ARP, 8,420′) and began the first descent. The views of the valley ahead were breathtaking. It was nice to be running downhill, but now more frustrating to be stuck in the pack, as I couldn’t always run at my own speed. I also noticed–for the first but not the last time–that local trail etiquette was different from what I’m used to. While I stayed on the trail, runner after runner cut the numerous switchbacks, shortening the course. Huh? I’m not a stickler for rules, but staying on the official course seems like a pretty basic one. I wondered if these shortcuts were legal, or if runners hereabouts just didn’t care.

I ran through the first refreshment station at Baite Youlaz, as I still had plenty of fluids and hadn’t eaten anything, and continued on to the first aid station at La Thuile. About ten miles in, I saw La Thuile in the valley below.

La Thuile was super crowded–the pack was still tightly bunched–and I didn’t enjoy either the crowd or the long wait. I was relieved to fill my flasks and continue on my way. The next few miles were relatively flat and shady, climbing gently through a cool pine forest. I took the opportunity to pull out my toothbrush and toothpaste and and brush my teeth. That’s a strange thing to do only four hours into a race, but I have chronic dental problems and wanted to maintain my oral hygiene on the trail. A bit further along this stretch, I noticed a runner with a Polish name and bib. “Pochodzisz z Polski?” I asked, dredging out my long-dormant Polish. (I spoke it fluently back in the 1990s but haven’t used it since and am now barely able to converse.) We chatted for a minute in Polish, but then the trail got steep again and we saved our breath. We’d begun the climb to Col Passo Alto (9,368′), which was long, hard and increasingly hot, but the views and numerous day hikers on the trail mostly kept my mind off the work.

Around mile 17 I reached the aid station at Rifugio Deffeyes. The whole scene was picture-perfect, and I was delighted to find bowls full of polenta cubes. I filled a ziploc bag with polenta and cheese for the road. Just as I was leaving, I saw Megan come into view. I said a brief hello and continued on my way.

After Rifugio Deffeyes, the trail leveled off a bit before the last climb to Col Passo Alto. I enjoyed this stretch immensely: it felt easy, the weather was beautiful, and I was able to snack on polenta and cheese enroute. I don’t remember much about the col itself, but apparently I got through it and reached the next aid station at Bivacco Zappelli.

I stopped briefly at Bivacco Zapelli for my first bowl of orzo soup, a staple at every Tor aid station. I’d heard that it was bland, but this bowl seemed good to me. I finished it quickly and, as I was leaving the aid station, again saw Megan coming in. I waved until she saw me, then continued on.

Bivacco Zappelli was followed immediately by a steep climb to Col de la Crosatie (9,256′). This, for me, may have been the most memorable col of the race. It’s not the longest climb, but it is one of the steepest–rising 2,300 feet in 1.5 miles–and the afternoon sun was hot. I hadn’t been climbing long when I passed Shane, who was standing by the trail leaning on his poles. I hadn’t seen him since the start, and he looked a bit rough. We exchanged a few words, and I continued up. High above me, a long column of runners wound slowly up the switchbacks. I heard someone shout “Piedra!”–Spanish for stone–and a few seconds later I saw a large rock bouncing down the mountain side, crossing numerous switchbacks on its way. Yikes.

I must have been feeling relatively good, as I passed a lot of runners on this stretch. I saw my Polish friend and asked “Jak się czujesz?” (How are you feeling?) He said fine and asked about me. “W porządku,” I replied (ok), but then added “Trochę zmęczony” (a little tired). He laughed: we were all tired here.

The views got more and more spectacular, and eventually I reached what I’d thought was the top. This turned out to be a false summit–the trail continued upward–but some other runners thought it was good enough for a break. I don’t like stopping short of summits–too hard to get going again–so I continued on.

The last part of this climb got steep and technical indeed, with ropes set up to assist the runners. The exposure felt exhilarating, and the summit like the top of the world.

Now began a long, steep descent toward the next aid station in Planaval. The descent was, if anything, even more beautiful than the climb. I could see Lac Du Fond far below, getting closer and closer until we’d passed. The sun was setting, creating a magical light.

Near Lac Du Fond, I thought again about trail etiquette. I’d been stuck for a while behind a runner who was walking slowly while drinking leisurely from a cup. I was right behind him and made a point of being audible (he wasn’t wearing headphones), but he never offered to let me pass. Finally I asked if I could get by, and did. I had this experience more than once. Like the runners cutting the switchbacks, this was foreign to me. If I hear someone right behind me, I always offer to let them pass, and most US runners do the same. I chalked it up to cultural differences and made a point of requesting passage from then on.

The final descent to Planaval was steep and forested, with views of the valley below. The constant downhill was taking a toll on my legs, so I was relieved when Planaval came into view.

I didn’t stop in Planaval, as I knew the first lifebase in Valgrisenche was only four flat miles away. As I left the aid station, I heard someone call my name. It was Mat, waiting for Maureen to come through. He asked how I was doing. I said ok, but then added that I was tired and a little worried. I didn’t feel bad, but I felt like I’d done a hard 50k–which I had. While it’s normal to feel tired after 50k with a ton of climbing, it was dawning on me that I was only one-seventh of the way into this race. How was this going to work? I’d be terrified if I felt tired four miles into a marathon, or 14 miles into a 100-miler. How was I supposed to do those remaining 300k? Mat told me I couldn’t think that way; I had to stay in the here and now. Good advice, but also easier said than done.

The four miles to Valgrisenche felt like a slog. They were flat, partly on road, partly on trail. It got dark along the way, and I stopped to put on my light belt. I reached Valgrisenche feeling tired, demoralized and disoriented. English was scarce at the lifebase, and my follow bag wasn’t where it should have been, so it took the volunteers a while to find it. By the time I got the bag and started sifting through the contents, Megan had arrived.

We went inside and surveyed the food and drink. There were good options, like pasta with sauce and potatoes, but none of it looked appetizing to me. This wasn’t the food’s fault: my stomach, like the rest of me, just wasn’t feeling great. I’d have killed for some Gatorade Endurance Formula, but all I had was the sports drink I’d bought in Chamonix. This turned out to be gross: the milk solids gave it a…well, milky flavor, which, speaking just for myself, is a terrible idea. I stood around feeling dazed and halfheartedly tried to force some food down.

Before long, Shane arrived. Like Megan, he seemed to be doing fine. I felt less optimistic and told Megan I didn’t think I could do this. She told me I just had to keep going.

We went outside and rummaged through our bags. This would be our first night, and I wanted to be prepared: down jacket, rain jacket, rain pants, hat, gloves, spare light, extra batteries, emergency blanket, extra food, etc. etc. My pack was getting full, but I managed to squeeze everything in, and soon we were off.

Megan and I had run on our own the whole first day, but we went into the first night together. I can’t remember if this was an explicit choice, or if we just realized we’d need some help to get through the night. Either way, it was a good call. My memory of that first night is sketchy, and I have no pictures to help me out, but I remember that it was hard and something I didn’t want to do alone.

The first aid station after Valgrisenche was Rifugio Chalet de L’epée. We stopped here briefly, and I put on my down jacket. We’d already climbed over 2,000′ since Valgrisenche, and it was getting cold. Almost immediately, however, we began a relentless climb toward Col Fenêtre (9,325′), and I quickly got hot and stopped again to take the jacket off. When I resumed hiking, I could see lights above me and grass alongside the trail, but not much else.

As we got higher, it got colder, and I stopped again to put my jacket on. I would regret this almost immediately once the trail got steeper, but I decided I couldn’t stop every ten minutes to change, and kept going. I soon caught up with Megan. We must have been moving fairly well, as we kept passing people, including someone named Marie whom we’d passed sometime earlier. But there were always more people ahead: a long line of lights stretched along the switchbacks above. I didn’t like to look up, as it reminded me how far we still had to climb, but the lights snaking above and below were admittedly a pretty cool sight.

The trail continued to get steeper. Megan and I concurred that this was insane. I dropped some kind of f-bomb every hundred yards or so: “Are you f***ing kidding me”; “F*** me”; “Oh my f***ing God”, etc. While this may seem excessive, these cols were unlike most passes I’d traversed in the Sierras or Rockies. The US has equally high and steep mountains, but Americans like their switchbacks, so the grades tend to be gentler. These trails cut nearly straight up the mountainside, so we kept hammering out a thousand or more feet per mile, usually for several miles at a time. Moreover, the cols typically got steeper and steeper as you neared the top–hence the ubiquitous ropes. We found another one here, and used it to haul ourselves to the top.

The descent was predictably long and steep, but it got easier toward the end, giving us a chance to admire the stars and crescent moon. It was beautiful out here, even at night. We soon reached the aid station in Rhemes-Notre-Dame, just a minute before Shane. We’d settled into a consistent pattern in which he’d fall behind on the uphills but catch up on the downhills. We were all tired, so we sat a while in the warm aid station and imbibed what we could. I allowed myself my first coffee of the race. I’d hoped to hold off longer–it was only 1:30am–but I thought I was going to need it to get through the next col. Shane ate some orzo soup and said “Do you realize we’re gonna be eating this same pasta soup for the next five days?” He paused a moment, then added “We’re gonna die out here.” For some reason I found Shane’s delivery hilarious, but on retelling, Megan has never seen the humor. Delivery is everything, I guess.

We launched into the next climb, to Col Entrelor (9,853′). Someone had told Megan this col wasn’t as bad as the last one, but I found no evidence for this claim. It was the same grindingly steep switchbacks that went up and up forever. We passed Marie again–she must have passed us during our half-hour break in Rhemes-Notre-Dame–and after a lot of effort and another rope, we made it to the top.

While it was nice to be done with climbing, the descent was hard, dropping over 4,000 feet in five miles. It was also treacherous, littered with rocks that rolled when you stepped on them. We sent several tumbling down into the dark. Megan decided to hang back with a Ukrainian woman we’d just met, while I went on ahead.

I was making good time when my world suddenly turned upside down. Or rather, I did. I stepped on a rock that flew out from under me, sending me tumbling. The descent was so steep that I couldn’t control my fall, and I tumbled down the hillside for a while, hitting rocks on the way. It was scary, and could have been bad: I could have hit my head on a rock; my poles could have snapped beneath me; I could have broken a limb. Fortunately, none of these things happened, and I rolled to a halt with nothing worse than bruises and some new holes in my down jacket. I was pretty shaken, though, and when I reached the bottom of the hill, I sat down to wait for Megan. She and the Ukrainian arrived a few minutes later; I hauled myself to my feet, and we jogged the last easy mile to the aid station at Eaux Rousses. It was now 6:00am on Monday, September 11, so we’d been running 20 hours.

Eaux Rousses was warm and cozy, and it was nice to sit down for a while. Right on cue, Shane showed up a minute later. We chatted about the only thing on anyone’s mind, namely how insanely steep these cols were. I tried to eat some orzo soup but was having a hard time. In contrast to the soup at Bivacco Zapelli–which had a nice veggie broth and some actual veggies–this was basically just orzo in salt water. I got down most of the orzo but left the “broth.”

The three of us left Eaux Rousses together. I’d tied my jacket on my pack to dry, as it was thoroughly soaked with sweat, but it was so cold outside that I quickly put it back on. Drying would have to wait for sunrise.

Sunrise came pretty soon, as we began a gradual ascent toward Col Loson (10,804′). The beauty of our surroundings gave me an immediate lift. We passed a small shrine and a farmhouse with the region’s signature slate-tiled roof, then entered a spectacular valley that led toward the col.

This col was like the others: long and increasingly steep. I couldn’t compare it visually to last night’s (which I didn’t see), but it was more stark and barren than the previous day’s. With all the bare rock and scree, it resembled the high Sierras. Above me, I could see sections of the trail in the sunlight, but the surrounding ridges still kept me in the shade. I hoped to reach the sun soon, as it had gotten colder as we’d climbed, and my hands were feeling numb.

I noticed once again how many people were cutting the course. The marked course followed the switchbacks, but a track had been visibly worn that cut straight through the center. I’d see someone a hundred yards behind me, then, after rounding a bend, find them a hundred yards ahead of me. I found this annoying. Although I wasn’t approaching this race competitively, this obvious course cutting still rubbed me the wrong way. I didn’t know if it actually constituted cheating, as the race organizers had said nothing about the (im)permissibility of shortcuts. But it made me feel a bit chump-like as I stuck to the official course.

Reaching the top was a relief, as was the subsequent descent. In contrast to most of our descents, this one was gradual and runnable, if correspondingly longer. The trail wound slowly down into an expansive valley whose floor stretched out for miles ahead. Not far from the top, we passed a woman with a few bottles of Pepsi and some cups. I asked her if I could have some, but she said she was saving it for someone else, and I passed on empty-handed. Megan, not getting the same message as me, somehow finagled a cup.

We jogged easily along the valley floor until we reached the Rifugio Vittorio Sella. We stopped to refill our flasks, then continued toward the next lifebase in Cogne. The trail was more developed here, with several bridges and raised wooden sections, and we passed numerous day hikers who shouted “Allez!”, “Forza!”, “Bravo!” and other words of encouragement.

After a quad-pounding descent through the woods, we finally hit pavement and began the last stretch to Cogne. We could see the town in the distance, but those two miles of road felt really long. The best we could manage was a shuffle-y jog. We’d decided to shower and change clothes in Cogne, in the hope that this would revive us. As we entered the town and looked around at the shops and restaurants, I thought how nice it would be to rent a room, get some sleep, and then go out for dinner and a beer.

We didn’t do that, but instead made our way to the lifebase, which we reached around 1:30pm. It was larger than the first, and I found it a bit confusing, between the multiple rooms, the dearth of English speakers, and my less-than-optimal mental state. I finally found the toilets and was dismayed to find that they were squatters, i.e., holes in the floor. Not ideal when you’ve been running up and down mountains for 27.5 hours, but oh well. I used one, took a shower, and changed into my spare shorts, shirt and shoes. It all seemed to take forever. I then returned to the aid station area to consider my gear and get some food.

I grabbed some stewed apples and hard-boiled eggs and sat down with them and my follow bag. The bag was a mess. I’d packed way too much, which made my life harder in two ways: it complicated my decisions about what to bring–too many choices–and it made it harder to implement those decisions because I had to search through so much crap to find anything. In my fatigued state, this too seemed to take forever. But eventually I was ready to go.

Shane had decided to nap at the lifebase, so Megan and I left on our own. We’d been there an hour and a half: a long time, considering we hadn’t slept, but the break, shower and change of clothes seemed to have helped. Our legs still felt dead, but we were less haggard than we’d been. We half walked, half jogged a few kilometers down the road, then turned left at a stunning vegetable garden–biggest cabbages I’ve ever seen–to climb a single track. We briefly chatted with some American tourists who were curious what we were up to, then reached the next aid station–small and outdoors–at Goilles Dessous. I opted not to get anything there, as we didn’t expect to go much farther today. We hoped to sleep at Rifugio Sogno, only six miles further on.

The next six miles involved some climbing, but nothing like the cols we’d done so far. After a short ascent, the trail became gently rolling, and we were able to slip into an easy jog. The wide open landscape was uplifting, and, in the late afternoon sun, felt a bit like the Scottish highlands.

As afternoon turned to evening, we approached Rifugio Sogno. To our dismay, it was deserted and locked. We’d been careless in reading the Tor timetable: this rifugio, and the next, were simple waypoints. We wouldn’t have a chance to sleep until Rifugio Dondena. Megan and I disagreed on what to do: she wanted to stop and take a dirt nap, while I wanted to continue on. But when she realized that Dondena was only 4.5 miles further, she agreed to keep going.

We cleared a relatively low pass and began a long downhill. We could see far ahead, but the light was fading quickly, and the rifugio was nowhere in sight. This stretch seemed interminable, mostly because I was impatient, but also because it kept raising and dashing my hopes. We passed numerous structures, including another rifugio, each time hoping it would be Dondena. But each time it wasn’t, and we’d have to plod on.

We seemed to have hit a pack, as there were lots of runners around. Some passed us, and others we passed–including Marie for maybe the 17th time. She must have been quick at the aid stations, since we kept passing her despite her never passing us. It got dark and cold, and we stopped to don jackets and lights. Finally, and somewhat surprisingly, we rounded a bend and saw Rifugio Dondena just off the trail.

It was a large, imposing structure that seemed able to house many people. We walked around to the back and went inside. The foyer was warm and welcoming, with a fireplace on one side and a bar on the other. We asked if they had space for us to sleep and were happy to hear they did. Then we sat down by the fire and warmed ourselves. The bartender brought us spelt salad and beer, and when we asked what we owed, she said “Nothing.” I assume the Tor has mutually beneficial arrangements with the rifugios, but this was still a pleasant surprise. Sitting by the fire, eating real food and drinking beer, we felt more relaxed than we had in days. By the time we finished eating, it was 10:00pm, or 36 hours since the race had started. We were ready to sleep.

A rifugio employee led us to the room where we were to sleep. We didn’t know how this all worked, so she explained to us that we’d share this room with five or six other runners, we shouldn’t use our lights, and someone would come in and wake us after two hours. I wasn’t thrilled with the situation, as I’d hoped to take out my contacts and give my teeth a thorough cleaning–which would be difficult in the dark–and I also didn’t love being on the clock. Still, these rules were there for obvious reasons, so I couldn’t complain. I got into bed with hastily brushed teeth and my contacts in and tried to sleep.

“Trying to sleep” generally doesn’t work out well for me–hence my aversion to the clock–and it was also uncomfortably hot in the small room. I lay awake for longer than I’d have liked, but eventually fatigue took over and I managed to sleep for maybe 60-90 minutes before someone shook me awake. It was Megan, who’d woken up before me, but I was so out of it that I didn’t realize this until she told me later.

I got out of bed, gathered my stuff, and went out into the hall, where I slowly put on my shoes and gear. I found Megan downstairs along with Shane, who’d arrived more or less when we got up. He was in a bad place, saying he might drop out so he could enjoy the rest of his time in Italy. Megan encouraged him to keep going to see if things changed. I mostly kept silent and drank a first, then a second cup of coffee. I understood the impulse to drop and wasn’t sure I could credibly counsel someone against it.

We left together a little after midnight and headed downhill in the dark. This was a good place to start a “new” day, as the running was easy and initially not too technical. We all seemed to gather strength as we ran–Shane no longer seemed like someone about to drop–and made good time down the forested descent to the aid station at Chardonney-Champorcher. This was a bright, cheery aid station, and I downed two cups of orzo soup. In contrast to Eaux Rousses, the broth here was delicious, proving once again that not all orzo soups are created equal.

Chardonney-Champorcher was followed by five miles of easy trails through the woods, which brought us to Pont Boset. I’m not in the habit of taking pictures at night, but I regret that I took none of this stunning little village with its Roman bridges, narrow cobbled streets and ancient stone structures, all beautifully illuminated in the dark. All I can show here is this picture I found online:

After a quick stop at the aid station in the town center, we took a trail down to a footbridge across the river. Here we met a Spanish runner who ran with us the next few miles. The bridge was followed almost immediately by the steepest stone steps I’ve ever seen. Each seemed about as high as it was deep–maybe 18 inches by 18 inches–which would imply a 100 percent grade. That’s probably wrong, but they were steep. They’d been built long ago, perhaps in Roman times, and had been mostly reclaimed by nature. I wondered about the people who had used them, and how strong they must have been. I double-poled all the way up, planting both poles above me and hauling myself up. It was a lot of work, but better my arms than my legs.

That is, until my left hand started to hurt. The pain came on quickly: five minutes ago my hand was fine; now it hurt every time it pressed against the pole’s wrist strap. If anything, it was even worse on downhills. This had never happened to me before, but then, I’d never done a race this long or used my poles so much. I’d been using them hard for almost two days now, both to pull myself uphill and to cushion the downhills. This had spared my legs a lot of strain but had apparently taken a toll on my hands. I couldn’t quite place the pain: a bruise wouldn’t start hurting so quickly, so maybe my hand had cramped? I stopped using the poles for a bit, hoping a rest would help.

A few more miles of forested downhill brought us to a paved road that led to the city of Hône. As I left the forest, there was a palpable sense of space. It was a dark and moonless night, but lights high above outlined an enormous valley. To my left, I saw what looked like a bridge hundreds of feet above the river (but which, with the benefit of maps, looks to have been a mountainside highway). To my right, the illuminated Fortress of Bard towered above the adjacent village of Bard. Once again I took no pictures, but the view was basically this except that the sky above was completely black:

We crossed the bridge across the Torrente Ayasse, passed through Hône, crossed another bridge over the Dora Baltea, then headed down the Via Vittorio Emanuele II, the main street of Bard. After so many hours in the dark mountains, I was excited to see this ancient village and finally took some pictures.

After leaving Bard, we continued along the Strada Romana toward Donnas, where we’d find the next lifebase. Some of this was nondescript pavement, but one memorable stretch consisted of old Roman paving stones that passed beneath an immense rock wall. I couldn’t get over how much rock there was here: natural rock cliffs blending seamlessly into rock roads, buildings and walls. The picture below gives a sense, although everything felt much different in the dark.

The Strada Romana was followed by a long stretch of unremarkable road, which we made longer by missing the turn to the lifebase, overshooting by a few blocks. We turned back and soon arrived. It was now 5:45am on Tuesday, September 12, and we were 95 miles in. Megan had said that Jan was planning to meet us there with veggie pizza, which would have been fantastic if not for my still-queasy stomach. We didn’t see her when we arrived, so we went inside.

I used the bathroom–squatters again–then headed back to the main room. Dozens of runners sat or lay around in various stages of collapse. I slowly worked my way through two cups of coffee while I pondered my gear and my battery pack charged my watch and phone. The next lifebase was 55k away, and while I hoped to get there before dark, prudence cautioned me to keep all my night gear. Reluctantly, I resigned myself to keeping my pack full.

My stomach wasn’t great, but I found once again that stewed apples and boiled eggs went down easily, so I ate as much of these as I could. We weren’t going to sleep here, but I lay down on a mat for ten minutes while Megan looked for Jan and Shane went on ahead.

Those ten minutes of prone immobility felt pretty sweet, but they couldn’t last. I went outside and found Megan and Jan, who had brought the promised pizza. It looked amazing, and Megan at least was able to eat some. We said goodbye and headed out.

It had gotten light while we were in the lifebase–we’d again stayed around 90 minutes–and I now got my first glimpse of Donnas. I was blown away. High valley walls rose on both sides, lined with row after row of stone terraces and vineyards. Once again, I was struck by the sheer quantity of rock, and how the built environment seemed to grow organically from the valley walls.

As we jogged toward the next town down the road, Pont-Saint-Martin, local residents cheered us on. There weren’t crowds of spectators, just pedestrians who knew what the race was about. I thought about how different this was from US ultras, which typically steer clear of towns. I was glad the Tor didn’t: I enjoyed the mountains, but these towns were worth seeing too.

Case in point: we soon reached the eponymous Pont Saint-Martin, a magnificent Roman bridge dating back to the first century B.C. To my delight, the course led directly across the bridge, giving me a chance to see it up close. It’s a cliché to marvel at Roman ruins that have stood for thousands of years, but: I still marvel at Roman ruins that have stood for thousands of years. The views from the span were pretty good, too.

After crossing the bridge, we ascended a stone path that led into the hills overlooking Donnas and Pont-Saint-Martin. I’d been bullish on this place already, but it was on this climb that I really fell in love. The hillside was basically an enormous garden, with backyard terraces growing every kind of fruit and vegetable: not just the ubiquitous grapevines, but also apples, pears, plums, figs, pomegranates, squash, cabbages, tomatoes, eggplant… A true garden paradise.

I was feeling pretty good, between the surroundings and my two coffees at the lifebase. Megan seemed less enthusiastic, but when I asked her if she was feeling ok, she just said (reasonably) “I’m tired.” We had been going for nearly two full days now, with only an hour or so of sleep. I may have felt it less than her, since I always sleep badly before long races and am used to running sleep-deprived. My biggest problem remained my left hand. The rest at the lifebase helped a bit, but it still hurt, which made me doubt that it was just a cramp.

After a long climb, we entered a rolling stretch–partly trail, partly road–above the Lys Valley. This provided some great views down to the villages below. We continued to the next aid station in Perloz, a charming little village overlooking the valley. When we arrived, someone was playing a whole rack of cowbells suspended from a wooden frame. Cowbells are standard aid-station fare, but this was new and contributed to the monastery-like feel of the place. (Sadly, the concert ended before I thought to take a video.) The aid station had some nice pastries and orange juice: I took some of the former and Megan the latter.

A steep downhill took us to the river Lys, which we crossed on a stone footbridge. We then passed through several villages on a paved road. Almost every car that drove by cheered us as it passed, and we talked appreciatively about how supportive the locals were, as if the race was a local tradition. Megan observed that “They act as if this race has been going on for hundreds of years,” even though it only began in 2010. Maybe they respected the effort we were making to see their home region; maybe they also knew that events like these are now their economic lifeblood. Either way, the support was nice. It reminded me of the Vermont 100, where the locals also come out to cheer, hand out food, and spray the runners with garden hoses.

Between the villages of Ver Follié and Le Mont du Suc was a long, flat runnable trail that we exploited as best we could. This was an easy, pleasant stretch except for the occasional soiled toilet paper. Megan and Shane had talked previously about the “poop bandit,” but I hadn’t noticed the bandit’s fingerprints until now. Here, though, it was hard to miss: the toilet paper lay just a foot or two from the trail, with no attempt to cover it. We talked about how this was terrible trail etiquette and how the organizers should say something to the runners, if only so they don’t give the race a bad name. I mean, it’s not that hard to find a discreet spot off trail where you can bury your poop. But I’ve heard that not all places share the “leave no trace” ethos of US backpackers, so maybe this is par for the course? I remarked that while Italy has many strengths–art, architecture, food, etc.–waste disposal has famously never been one of them.

In Le Mont du Suc we began to climb some really steep steps…and climb, and climb, and climb. These steps weren’t as crazy as the ones after Pont Boset, but they were very steep in places and went on forever. It was a relief to reach the aid station at La Sassa, which broke up the climb, and where we caught up with Shane. This was the first aid station to serve beer, and both Megan and I enjoyed some IPA. We also spent some time hugging the aid station’s aggressively friendly golden lab.

Not long after La Sassa, we returned to single-track trail and continued to climb relentlessly. There were a lot of day hikers out here, and also cows.

After some more climbing, I stopped to put on sunscreen, telling Megan and Shane I’d catch up. I assumed I would, but a short while later I had to make a pit stop and, more importantly, decided I had to do something about my hand. It had grown more and more painful over the last few miles of climbing, and something had to change. If it was bruised, maybe wrapping it in tape would help? I took out the tape I’d brought for ankle sprains and wrapped the hand and wrist. I started hiking again, but soon realized I’d wrapped it too tightly and stopped to redo the whole thing. It was now becoming a mess, as the tape got twisted and stuck to itself, so this took a while. And in the end, it was pointless: my hand hurt as much as ever. The next half-mile was frustrating, as I stopped repeatedly to adjust the tape, my wrist straps, anything that might alleviate the pain. Nothing worked. Person after person passed me, and I wondered if I’d ever catch Megan and Shane.

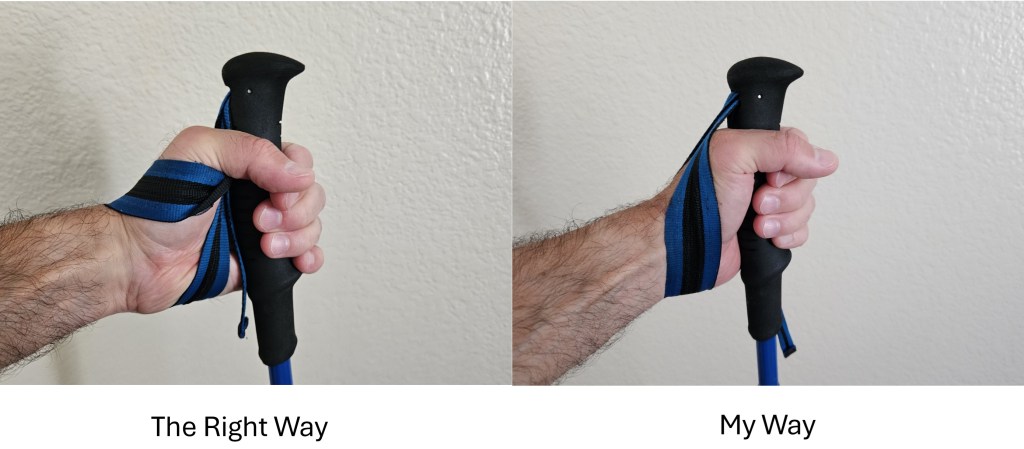

I thought about a podcast I’d listened to on the subject of poles. The hosts and guest were very bullish on poles–which could take stress off your legs–and said something like “No one has ever DNF-ed because their arms gave out.” That made perfect sense to me at the time, and still does, but I began to wonder if I’d be the first.

The final approach to Rifugio Coda was an exposed ridge that offered impressive views. Ahead I could see the rifugio; below I could see Lago Montagnit with two stone houses behind it. Both the rifugio and the houses are tiny in the pictures below, but if you blow them up enough you’ll see them at 12 o’clock.

Megan was waiting for me at the rifugio. She’d been there about half an hour, while Shane had continued on alone. I explained my situation to her, saying I wasn’t sure I’d be able to finish. I couldn’t do this race without poles, and I couldn’t use poles without hands. She told me I should seek medical help, and I resisted, thinking there was nothing they could do. Eventually I relented and talked to a medic, who said there was nothing he could do except give me ibuprofen, which I already had. But then he actually gave me something much more valuable: he showed me how to use my wrist straps. I’d been using them wrong this entire time, inserting my hand from above and pressing the outside edge down on the strap. I should have been inserting my hand from below, so that most of the pressure fell between the thumb and forefinger. I felt sheepish for not knowing this already, but I’d never done races longer than 100 miles, and I guess you can get away with a lot in such comparatively “short” races. In any case, it was too late to undo whatever damage I’d done, but at least the new technique shifted the location of the stress. Between that and some ibuprofen, maybe I’d get by.

Having tended to my hand, I took advantage of the rifugio’s cuisine. They had pizza and quiche, and I quickly gobbled down two pieces of the latter. I could easily have eaten two more, but they seemed to be doling it out sparingly, and Megan had already been here a long time. So, finally, we got going again.

The next stretch, to Rifugio Barma, had no extended climbs or descents, just a lot of up and down. The weather was nice as we set out, but it soon got cloudy and then began to rain intermittently. The vegetation was thick here, and brushing against it soaked us even in the absence of rain. As the miles went by, we passed numerous stone structures, each time hoping it would be the rifugio, each time disappointed. I wondered what these structures had been used for back in the day, and when that day was. Some were mere stone sheds–probably granaries or stables–but others were true mansions that could have housed whole families in style. It seemed crazy that they’d just been abandoned out here, but this was admittedly not the most convenient place to live.

Along this stretch I met a runner–a bearded Dutch guy–who said “You look familiar.” Turns out we’d met the year before at SwissPeaks. He was doing the Tor des Glaciers, which overlapped in places with Geants. We ran together for a while, chatting about races we’d done or would like to do, and I thought about what a weird little ultrarunning world this was.

Finally Rifugio Barma came into view. It sat above Lago della Barma and was surrounded by a basin of weirdly twisted rocks. We were glad to arrive. We parked ourselves at a table and ordered two bowls of polenta with tomato sauce, then two more. Perhaps it was just my state of mind, but that polenta seemed like the best thing I’d eaten since the race began, and possibly ever. “This makes me happy,” I said to Megan, meaning the polenta, the rifugio, everything. Megan seemed less enthused and expressed some concern about her knee.

As content as I felt there, the light was fading, so we wrested ourselves back onto the trail. Megan again mentioned her right knee, which apparently now hurt to bend. That didn’t sound good, but we get a lot of aches and pains on the trail, and I figured it would be ok.

After a rocky stretch that reminded me of Desolation Wilderness–rocks piled on rocks–we hit a dirt fire road. Shortly thereafter, the rain began to pour. We saw an abandoned shack and dashed inside to put on our rain gear. This made sense at the time, but less sense a few minutes later, when the rain let up. We felt silly–not to mention hot–in our waterproof gear, but I’d been burned before by not taking rain seriously. Too hot is better than dangerously cold, so I kept the gear on. It wasn’t comfortable, but I was enjoying the evening nonetheless. My hand was doing better since I’d fixed the straps, and the setting sun, clouds and rain blended into an ethereal light.

Megan was not enjoying the evening. Her knee had deteriorated badly, and she had slowed a lot. The climb up Col du Marmontana (7,698′) hadn’t been too bad, but the next descent…was. Megan couldn’t bend her right knee and was going down the mountain sideways, which is as terrible as it sounds. I’d go a few dozen yards ahead, stop, and wait for Megan to catch up. This is not sustainable, I thought. Even if she could keep going like this for another hundred miles–which seemed unlikely–we were moving so slowly that we’d eventually miss a cutoff. Still, I didn’t dare ask the obvious question: Do you think you should drop? As hard as this process was for me, I knew Megan was feeling a lot worse.

At last we saw the Lago Chiaro aid station below us. If you squint, you might be able to see it at 4 o’clock in the picture below. For those who don’t like squinting, the next picture shows a grainy blowup.

When we got to Lago Chiaro, Megan asked me to get her some stuff from the aid station while she waited off to the side. She was crying and didn’t want the volunteers to see her this way. The aid station seemed poorly stocked, and no one spoke English, but I managed to find a few things and brought them out to Megan. She was in a bad place. I pushed her, as she had pushed me, to ask for medical help, and eventually we spoke with a couple of volunteers. One offered to tape Megan’s knee, and while this seemed like a Hail Mary, it probably couldn’t hurt. We thanked them and headed slowly toward the next aid station at Colle Della Vecchia.

The journey to Colle Della Vecchia was more of the same. The uphills weren’t too bad, but the downhills were excruciatingly slow. Until Megan’s knee went bad, we’d been averaging 2.5 miles per hour, including stops. We weren’t even hitting 1 mph now. I wondered what I would do. If Megan dropped soon, I might still be able to catch up with Shane. But that became less and less likely with each slow mile. I whiled away the time by trying to work out my surroundings in the dark. In some places I could see rock faces across a chasm, and I could tell we were surrounded by high cliffs and rocks. I would have liked to see this section in daylight, but you can’t see everything when you’re doing a third of your race at night.

At Colle Della Vecchia, a volunteer told Megan she had two options: she could continue on foot, or they could call a helicopter to have her airlifted out. Neither option sounded great, so we were relieved when he suggested a third: she could sleep here for a couple of hours. They had a tent with two cots behind the aid station, and offered one to Megan. I thought they’d offered the other to me–if Megan was going to sleep, I wanted to as well–but they seemed surprised to find me settling in next to Megan. Oh well. I didn’t have much hope that a short sleep would fix things, but right now I just wanted to stop thinking about it.

I was woken 90 minutes later, as there were other runners who needed the cots. I was soaked in sweat and pretty out of it when Megan told me she planned to continue on foot. “That’s crazy!!” I said, perhaps a tad too vehemently. I understood her aversion to being airlifted, but I was genuinely afraid of going out there with that knee. These mountains are hard even with sound legs, and it seemed insane to attempt them with a knee that didn’t bend. But, Megan was resolved, so I drank some coffee and headed into the night.

The next few miles to Niel were predictably slow, but not as bad as I’d feared. Megan wasn’t getting any better, but she wasn’t getting worse either. The trail became less steep once we entered the woods, which helped. Eventually I realized she was going to make it–it would just take a long time. I also realized that my race, like hers, was almost over. I could in theory continue on my own, once she dropped, but catching Shane was now out of the question. We’d gone too slowly for too long; I’d lost my motivation and didn’t see myself getting back in the game. Accepting this was actually a relief, as I stopped worrying about our pace. I only had one goal left: getting both of us to the next lifebase in Gressony.

We arrived in Niel in a drizzly rain, at 4:45am on Wednesday, September 13. The aid station was in a large B&B, the Dortoir La Gruba, and felt like an upscale ski lodge: warm and wood-paneled, with high vaulted ceilings. Exhausted-looking runners sat around eating, drinking, or just crashing. A large witch’s kettle of polenta bubbled in one corner, and I ate a couple of bowls and drank some coffee. I overheard one man say he didn’t want to go out there again. I sympathized, but we couldn’t drop here, so after a short rest we headed back into the rain.

The climb from Niel began on a cobbled footpath that passed some abandoned stone structures. I noticed a runner snoozing in one of them, as I’d imagined doing several times. The stone path gave way to a dirt single-track that climbed steeply toward Colle Lazoney: almost 3,000 feet in two miles. Some people say this is the most difficult climb of the race, but it didn’t feel that way to me. Moving slowly has its perks.

The skies started to lighten as we approached the top. It was cold and wet, but the world had a ghostly beauty, and I took a minute to savor what would be my last summit view. Then we began the long, gradual descent toward the Bleckene – Lòò Superior aid station.

Bleckene – Lòò Superior was a welcome sight, as it meant we had only five miles of easy descent to go. Some volunteers saw Megan arrive and, noticing her obvious limp, asked how she was doing. There seemed to be a faction that wanted to airlift her out, which I found amusing. If she hadn’t taken the airlift at Colle Della Vecchia, she wasn’t about to do so here, five easy miles from Gressony. But they kept saying “Three hours! With good body!”–clearly implying that Megan’s body was not good. Fair enough.

The remaining miles were easy but slow–so slow that I began to fall asleep on my feet. I told Megan I had to move faster to stay awake, so for the next few miles I’d repeatedly jog ahead, sit down next to the trail, close my eyes, and wait for her to catch up. Many runners passed us here. Runners’ bib numbers are based on their ITRA scores, and for most of the race we’d been surrounded by bibs in the 100s and 200s, like our own. Now we were seeing bibs in the 500s and 600s, letting us know how far we’d fallen back.

At last we left the woods, and two miles of paved road brought us to the lifebase in Gressony. Jan, who was staying there, met us when we arrived. We explained what had happened, and she generously offered to let us shower and rest in her room. We gratefully accepted, as we were in no shape to fend for ourselves. In the last 73 hours, we’d traveled 136 miles, climbed 48,000 feet, and slept three hours. We would have liked to go on, especially Megan, who worried she hadn’t lived up to the spirit of Lucas. But the last 18 miles–from Rifugio Barma to Gressony–had taken us 18 hours, and it was time to pack it in. So at 11:30am Wednesday, we picked up our follow bags, told the race officials we were dropping, and were done.

While Megan was in the lifebase, I talked with Jan about Megan’s knee. I knew Megan felt bad about dropping, particularly when she’d received the scholarship, so I emphasized that she was one of the toughest runners I knew, that this was her first DNF, that she’d never drop just because she was tired–in short, that she had no choice. Megan re-emerged in the midst of this conversation, and Jan did me the favor of saying something like “When he was talking about you, I thought ‘Oh, he really loves her.'” I silently thanked Jan for that: my own DNF seemed more worthwhile if it got me some good press.

We showered and ate at Jan’s place, enjoying that surreal, luxurious feeling of no longer being on the trail. As we ate pizza and did our laundry, I arranged with our Airbnb host in Courmayeur to begin our rental a day early. Then we crashed for a couple of hours. When I woke up, I realized I hadn’t thought things through. I’d assumed there was public transportation from Gressony to Courmayeur, but there was none. Jan kindly offered to drive us back, but I was dismayed to learn that the drive was two hours each way. Our journey had taken us to the other side of the Aosta valley, and we were now far from Courmayeur. I regretted reserving the Airbnb for tonight, as this would leave Jan driving home in the dark, but she was an indefatigably good sport and dropped us off in Courmayeur that night.

Our only plan for the following day was to bring some food to Shane at the lifebase in Ollomont. Our race was over, but he was still carrying the Bay Area torch, and we wanted to help if we could. We stopped in the town of Aosta to look for alternatives to aid-station fare, like gyoza, fruit smoothies, and avocados. This took a while, and when we checked the race tracking info again, we realized we were in danger of missing him. The tracking data were updated infrequently, and he was farther along than we’d thought. We drove to Ollomont as fast as we could and, after a short search, found him in the lifebase cot room. He seemed to be doing ok, considering he’d been moving for two days since we last saw him. He was able to eat, in any case. We spent a few minutes catching up, then let him get back to his race and drove back to Courmayeur.

Megan woke up feeling sick the next day, but we hoped to catch Shane at the finish, so we went into town nonetheless. We knew he’d finished but weren’t sure where he’d be. We checked out the finish area–finally seeing the finish line we hadn’t reached–then walked to the Sports Center and found him there. We congratulated him on a tremendous feat, got some pizza, and heard about the rest of his race. I felt a little envious hearing about the places and hallucinatory sleep deprivation I’d missed.

Megan felt too sick to do much else, so she went back to bed while I met up with Jan to tour some castles. The Aosta Valley has many of them–there seems to be one on every hilltop–and I was glad for the chance to relax and spend some time with Jan. She’d been such a help to us, but things had been so hectic–or we’d been so exhausted–that we hadn’t had much time to just hang out. An afternoon seeing castles fit the bill.

Later that evening, Megan and I met Jan for dinner at the Ristorante Ancien Casino. It was a festive spot, right next to the finish line, and Jan exchanged greetings with what seemed like half the runners seated there. Megan and I were amazed at how many people she seemed to know, but I guess she has been coming here for years. I enjoyed an absurdly large flagon of beer–I believe the technical term is a yard–as I watched the runners come in. I felt a twinge of regret at not being among them, but all in all, I couldn’t have asked for a better last night in Courmayeur.

We went back to the finish on Saturday morning, hoping to see Maureen–our last friend in the race–come in. By noon we had to get on the road, so we walked back toward the car. The Tor course came down from the hills only a block from the parking garage, so we decided to take a last look up the trail. Right at that moment, Maureen came down the hill, finishing with a few hours to spare. A good finish for her, and for us. We swung by Mat’s car to drop off some unused power bars and other things we didn’t want to bring back, then headed back to Geneva.

We spent our last night in an airport hotel, as we were flying out the next morning. There weren’t a ton of restaurants within walking distance, but there was a nice fondue place not far away. We’d never had fondue in Switzerland, so we decided to cross that off our bucket list. Then we walked back to the hotel, I asked Megan if she’d like to get married, and she said yes.

While this may seem like a surprise ending–it was to Megan–I’d been planning it for some months. Two big things had recently fallen into place: Megan had settled into a new career, and we’d finally moved in together. Even so, I probably wouldn’t have thought to propose without the Tor. It seemed like the right occasion: not only would it be memorable, but supporting each other through the race would be a fitting metaphor for marriage and how our relationship had evolved. With this in mind, I’d brought an engagement ring with embossed malachite mountains to symbolize the journey we’d been on:

I’d carried that ring through the whole race, thinking there’d be a perfect moment to propose. In my mind, it would probably happen right before the finish–maybe looking down from the hills above Courmayeur–so we could celebrate our engagement by crossing the line. Needless to say, that’s not how it went. Once our race went south, I realized Plan A was out, and I didn’t have a Plan B except to hope for another opportune moment. It never came: first we were busy, then Megan got sick, then we were going home. The airport hotel was simply my last chance to ask while still on this trip. But while it wasn’t the perfect setting, I’m glad things turned out as they did. The race proved a better metaphor than I’d hoped: we’d supported each other through good times and bad, and had stayed together when we could have gone on alone. That seemed more meaningful than the Instagram moment I’d originally sought.

And that goes for the race as a whole. It didn’t turn out as hoped, but in many ways it surpassed my expectations. The course was beautiful and varied in ways I hadn’t foreseen. Running without sleep was easier than I’d expected–it turns out you don’t need many brain cells to keep putting one foot in front of the other–and didn’t diminish my enjoyment of the race. Until Rifugio Barma, we were having the time of our lives, and the stretch beyond Barma was memorable if not fun. We got to make new friends, both during the race and after. Given all that, it’s hard to feel bad about the DNF.

My question going into this race was “Why?” This post is my answer.

It’s now July 2024, and we’re signed up to do the Tor again in two months. We’re better prepared this time, having learned some important lessons:

- Don’t overstuff your follow bag;

- Do find space in your pack for Gatorade Endurance Formula;

- Train your legs for the downhills;

- Learn how to use your poles. (I never got a firm diagnosis on my hand, but it took more than two months of complete rest to recover, which makes me think it was a stress fracture.)

With luck, we’ll finish the course this year.

Oh, and while we didn’t manage to steal a Tor poster, we did buy an autographed print for our wall. It’s a nice piece of work.

One comment