The Miwok 100k is, as its website claims, an iconic trail ultramarathon. Back in the day, it regularly attracted a who’s who of elite runners, who often used it as a tune-up for Western States. Things have changed: there are way more April/May races these days, including the high-profile Canyons 100k, and Miwok now feels more local and laid-back. But the course’s signature feature–gorgeous views of the Northern California coast–remains as alluring as ever.

The course begins in Stinson Beach, goes up the Dipsea trail to Cardiac, drops down Coastal to Muir Beach, does a big loop around the Marin Headlands, heads back up to Cardiac, then does a long out-and-back to Randall trailhead before finishing at the Stinson Beach community center.

Along the way, you pass some of the best coastal scenery Northern California has to offer. For reasons that will become obvious, I didn’t take any pictures this year. But on a nice day, you’d see views like this:

I’d wanted to do Miwok for years. I began entering the lottery in 2017, but race entry used to be more competitive, and for several years I failed to get in. My consolation prize was pacing Megan in 2017 and 2018 (when she won), both of which were beautiful years with abundant sun and wildflowers. That whetted my appetite to do the race, and by 2023, that had become pretty easy. With more races for runners to choose from, the lottery was gone, and now basically anyone who wants to register can do so. My race in 2023 was…ok. The running was fine, but the weather was disappointing: rain for the first few hours and thick fog for the rest of the day. No coastal views, and no sun to bring the wildflowers out. I was still craving that perfect Miwok experience. So when Megan suggested doing the race this year, I naturally agreed.

Sadly, as race day approached, it became clear this wouldn’t be my year. A week out, the forecast said there was a 30 percent chance of rain. That rose to 80 percent, then 90, then 100. I started seeing stories like this:

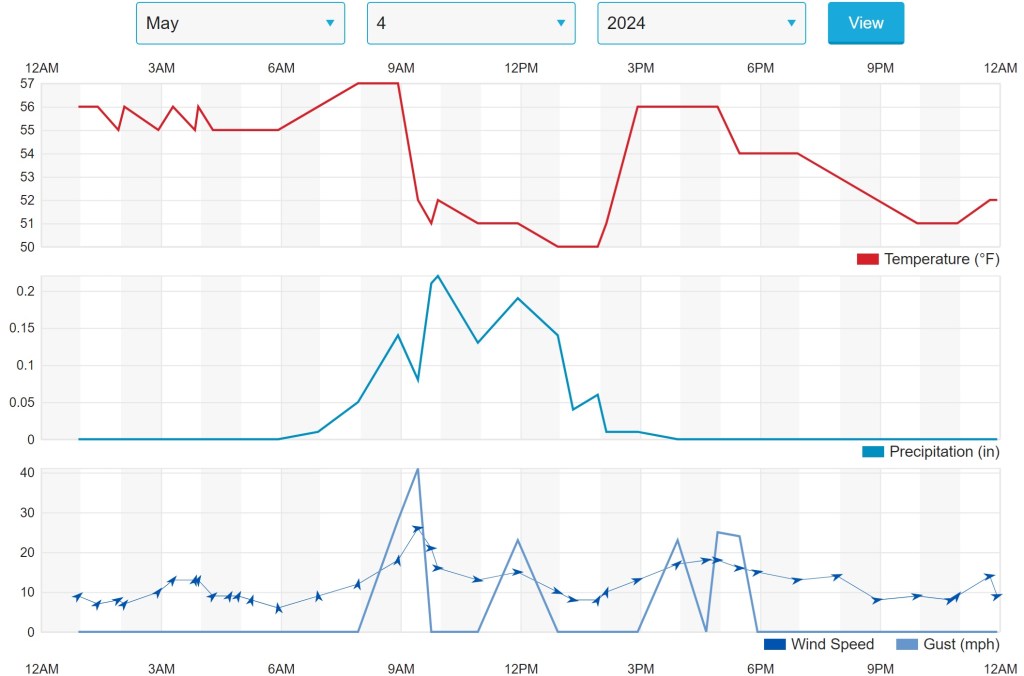

To add insult to injury, this storm was going to be quick but ill-timed. Monday through Friday were sunny and beautiful, as Sunday promised to be. On Friday evening, there still wasn’t a cloud in the sky. The storm would last only twelve hours–which, unfortunately, coincided perfectly with the race. Here’s how the weather ultimately turned out:

Oh well. Bad and unpredictable weather comes with the ultrarunning territory, so I shouldn’t complain. But the forecast definitely dampened my enthusiasm, as my main reason for running was to get the uplifting Miwok experience I didn’t get last year. That clearly wasn’t going to happen.

Race day began uneventfully enough. Miwok has a 5:00am start, but with pre-race traffic on Highway 1, the trip from San Rafael could take an hour, so we planned to leave before 3:30. I managed to get to sleep early but then woke up hours before my alarm, so I ended up getting maybe three hours of sleep. I drank a ton of coffee, left by 3:30, and parked at Stinson at 4:15. The weather was not bad at the start–not really raining and fairly warm–so we took off our jackets before the race and started in t-shirts.

Nothing notable happened in the first few miles except that, while climbing Steep Ravine, I noticed my heart having arrhythmias. (Thus allowing Cardiac Hill to earn its name.) I wasn’t too concerned, as the cause was obvious: I’d tripled the strength of my morning coffee and was awash in caffeine, which, combined with strenuous exercise, has always had this effect. I decided to throttle back a bit until the caffeine had worked its way out of my system. I soon heard the bagpipes at Cardiac, reached the top, and headed down Coastal.

This part of the race felt ok. I was in a mental fog, between the limited sleep and the weed I’d smoked (apparently in vain) to get it, but I was awake enough to navigate the technical downhill in the dark. I saw Megan a short way ahead of me, which was comforting. I stopped to pee just before Heather Cutoff and lost her there, but I figured I’d catch up. It wasn’t long before I saw her again, heading out of the Muir Beach aid station (mile 8) as I was heading in.

I next saw her, maybe 200 yards ahead of me, on the long climb up Marincello, about 13 miles in. I was still feeling ok and figured I’d catch her soon, but not long thereafter my race really went downhill. After cresting Marincello, the wind and rain picked up, and I wondered if I should put on my jacket. I decided to wait a little longer: I still wasn’t that cold and figured the day would get warmer as it progressed. (As the above weather graph shows, that was not to be.) I finally decided to put on my jacket when I reached the SCA trail–at which point the wind was really howling–but that proved too late. By then, my fingers were too numb to work the zipper, and I fumbled for a while trying to zip the jacket up. (I tried yelling obscenities at the zipper, but, surprisingly, that didn’t help.) Eventually it was done. I thought, with the jacket now trapping my body heat, I’d warm up quickly, but I continued to get colder and colder. I pulled my hands into the sleeves and tightened the hood around my visor–pushing the brim down and narrowing my vision to a small patch of trail in front of me–but I couldn’t warm up. My teeth were alternately chattering and tightly clenched; my whole body tensed up from the cold, and my breathing became rapid and labored in some kind of stress response. It was awful, but I still hoped I’d warm up as I ran along.

My left hip flexor had been sore the week before the race, and it started bothering me around now. That concerned me: it wasn’t awful, but I worried that it would worsen as the day went on. I wanted to take an ibuprofen but couldn’t imagine fishing one out in this wind and rain, so I kept running. I reached the Bridge View aid station (mile 18)–where there was no view of the Golden Gate bridge–and continued down the Julian trail. I was still cold, but the wind was less intense now that I was off the ridge.

Julian is usually a fun runnable downhill, but I couldn’t wait for the long climb up the Rodeo Valley trail, which I hoped would warm me up. It did, a little: Rodeo Valley was sheltered, and the long climb warmed me a bit. I was still cold, and my teeth were still chattering, but I felt less desperate than I had a few miles back. I started to hope that maybe I was out of the woods, and I managed to take an ibuprofen.

That respite didn’t last long: once I’d climbed Rodeo Valley onto the ridge, the wind picked up again, and my thoughts turned dark. My main concern was the hip flexor, which was now quite painful, and I wondered if I’d be able to finish the race. One thought comforted me: I was now pretty sure the hip flexor pain was related to the cold, since it noticeably worsened when I got colder but improved whenever I warmed up even slightly. That made sense: that muscle probably had to work a lot harder when my whole body was tense and locked up from the cold. I found that encouraging, as it meant the problem might go away when the day got warmer–which it would, right?

I kept wondering when and if I should refill my flasks. I was running today with two 500ml flasks, but so far–now 23 miles in–I hadn’t taken so much as a sip. Should I try to down one and refill it at Tennessee Valley (mile 26)? I couldn’t bring myself to drink in this cold, so I decided I’d refill at Muir Beach (mile 30). I wasn’t eating, either: with my body so tense and my teeth constantly clenched, I didn’t feel I could.

When I passed through Tennessee Valley, I grabbed a bunch of potato chips and continued on. I’m not sure if chips are the ideal race food, but I found the salt comforting, and it was something. I jogged along Coastal to Muir Beach, in my own world except for the small opening in my hood. At Muir Beach I decided not to refill the flask–I’d still drunk almost nothing–but I did grab a couple of chocolate chip cookies for the road.

The climb back up Heather Cutoff was another opportunity to warm up: it’s sheltered and continuously uphill, and my shivering subsided a bit. For the first time that day, I found myself talking to another runner: a Finnish man who, along with his wife, was doing this race as a Western States qualifier. We chatted all the way up Heather Cutoff, but when we reached Coastal I picked up the pace and left him behind. Coastal is quite exposed, and I wanted to run faster to keep warm in the wind.

For some miles I’d been wondering if I’d need to drop out, and if so, when. I kept telling myself I’d put off the decision till Cardiac (mile 35), at which point I’d have more data. Now that Cardiac was only two miles away, I began thinking about this a lot. I was freezing. My cheap old rain jacket was soaked through, and the wind was whipping away any heat I was generating. My hip flexor hurt. The thought that kept haunting me was: What if I can’t run any more? What if my body locks up and I can’t run and I have to walk? What if that happens when I’m miles away from any aid? The stretch beyond Cardiac was long and lonely, and I was genuinely afraid of hypothermia. The only thing keeping me survivably warm was running, but if I had to walk, I’d get real cold real fast.

The race website emphasizes that if you choose to drop, you have to tell an aid station captain and turn in your bib–otherwise, they might think you’re in trouble and call search and rescue, on your dime. The next aid station after Cardiac is Bolinas (mile 42). That didn’t seem like a great drop option, as it would require me to go seven miles past Cardiac to Bolinas, then another seven miles from Bolinas back to Stinson Beach, all on an exposed and windy ridge. That seemed like plenty of opportunity to get hypothermia if things went south. On the other hand, I’d pass the Matt Davis junction only a few miles past Cardiac, where I could cut straight down to Stinson Beach. Surely it would be fine to do that, and just tell officials at the finish that I’d dropped? I convinced myself that would be fine, and resolved to continue on to at least Matt Davis.

As I approached Cardiac, a runner passed me from behind and gave me the most memorable sight of the day. He was unusually heavy for a runner–maybe 50 pounds heavier than you’d expect for someone his height–but what caught my attention was that he was running shirtless. Here I was, wrapped up in my rain jacket and worrying about hypothermia, and this guy runs past bare-torsoed, smiling like it’s a balmy day? WTF??? I’ve recently been reading Ed Yong’s book, An Immense World, about the different Umwelten–or perceptual universes–that different animal species occupy. This guy and I were clearly in different Umwelten. I suppose every body is well-adapted to some environment. His probably wasn’t ideal for running Western States in 100-degree heat, but he was clearly enjoying himself out here.

I stopped at Cardiac to refill the one flask I’d drained and to grab some more potato chips. When I told a volunteer I’d been near-hypothermic for 20 miles, he said “It’s so much warmer once you get past here–so much warmer!” That sounded promising, so I continued on.

As I left Cardiac, a couple of spectators cheered me on. I shouted back at them “I AM SO FUCKING COLD!!!” Not sure why, but I guess I needed to share that feeling with someone. It was, after all, the only thought I’d been repeating to myself for hours. On the Old Mine trail, a family shouted encouragement. I wish I could have at least smiled back, but my face was locked into a clenched-teeth grimace.

Over the next couple miles, I concluded that that Cardiac volunteer was full of shit. I know he was trying to encourage me to go on, which I appreciate, but it was not “so much warmer.” It wasn’t warmer at all. I thought again about taking Matt Davis down to Stinson, but it occurred to me that I’d have one more chance. A few miles past Matt Davis, I’d pass the Willow Camp trail, which I could also take down to Stinson. That, I decided, would be my last opportunity to bail. I still didn’t know what I was going to do, but I was grateful to have more time to make that choice.

I wondered again if I was eating and drinking enough. I was almost 40 miles in, and so far I’d consumed just one flask of Gatorade, two chocolate chip cookies, and a quart bag of potato chips. Didn’t seem like much.

As I approached Willow Camp, I realized I had one more option. Megan’s pacer, Shane, was meeting her at Randall, and he would presumably have a car there. Since Megan was ahead of me, I would run into them on the out-and-back, and I could, if needed, get Shane’s keys and drive myself back. Although the total distance (50 miles) would be the same as if I’d turned back at Bolinas, continuing to Randall would spare me the run back along the exposed ridge. And by continuing on, I’d leave open the possibility of warming up and actually finishing the race. I decided that was a sound plan and ran past Willow Camp.

I reached Bolinas feeling cold. My friend Jack was working there and remarked that this was good Tor training. I told him I might have to drop, as I was concerned about hypothermia. Another volunteer said they had hot broth at Randall, which was encouraging. I grabbed two chocolate chip cookies and moved on.

About two miles later, something miraculous happened: it started to feel warmer. This stretch of trail was heavily wooded, so there was no wind, but mostly the day had begun to warm up. The sun wasn’t out, but more light was filtering through the clouds, and the temperature change was palpable. It hadn’t rained in a while, and my jacket had begun to dry. I didn’t feel good–miles of tense shivering had taken a toll–but I started to think “I can do this.”

By the time I reached the top of Randall, I’d decided to finish the race. Even if it started raining again, I was recovered enough that I thought I could endure it. So when I passed Megan and Shane coming up the hill, I didn’t ask for Shane’s keys and just said “Top three!” Realizing that was probably unclear, I explained that this was one of my three most miserable race experiences ever. I don’t actually have a formal ranking, but in my head, the other two were Squamish 2014 and Boston 2018, the latter of which also had horrifically cold wind and rain.

As I ran down the hill, I thought a lot about that hot broth. I’d forgotten my reusable cup, but I wondered if they could fill one of my flasks with broth. That would be great: not only could I sip it along the way, but the heat against my body would keep me warm. It’s possible that no one has ever fantasized so much about broth before. My only concern was that, like many aid stations I’ve encountered, they might not have veggie broth.

As it turned out, they didn’t have any broth at all. Crushed, I turned around without getting anything and trudged back up the hill.

The return to Bolinas felt long, but I was no longer cold and knew I’d get there. For the first time that day, I felt thirsty and drained my remaining flask quickly. It was good to finally be drinking–I was over 50 miles in and had drunk only 1.5 liters–and I looked forward to refilling both before the final push back to Stinson. I passed a lot of runners who were on their way out, but there seemed to be fewer of them than last year–more DNFs because of the weather?–and many of them seemed in low spirits. No argument there: it had been a rough day.

I reached Bolinas, refilled my flasks, and headed into the final stretch. I mentally broke it down into the various sections I knew by heart, and focused on ticking them off one by one. I didn’t know my time or pace: I hadn’t looked at my watch since donning my jacket many hours ago, and I wasn’t about to start now. It was slow and kind of painful, but eventually, to my relief, I saw Matt Davis below me. I also saw something else: the sun. It had finally broken through, and as I descended through Matt Davis’s gnarly rocks and roots, I glimpsed the ocean shining below. Emerging from the woods, I crossed the finish line and found Megan waiting for me. I hugged her and said “That was a horrible, horrible experience.” “I’m proud of you for finishing,” she replied. “So many people didn’t.”

A few minutes later, in the warmth of the community center, I learned that Shane didn’t have a car at Randall: he’d parked miles away and had run there. That made me laugh: the one thing that had kept me going was a mirage. Still, I was grateful to Shane for pacing Megan and providing that hope. If I’d known the truth, I probably would have dropped at Willow Camp.

We drove home along the northern route, passing Olema and Point Reyes, so Shane could pick up his car. The weather was beautiful by then, which seemed like a cruel joke, but I couldn’t complain. I was happy to see blue skies and green hills bathed in sun, and felt relaxed for the first time all day.

I don’t think I need to do Miwok again. I might, since it’s local, but I don’t need to. In the end, I got my Miwok experience. It wasn’t what I’d hoped for: not fast (I was an hour slower than last year), not fun (I was cold and miserable the whole time), and not beautiful (I couldn’t see a damn thing). But after so many hours of thinking I’d DNF–hours of fear and discomfort and doubt–simply finishing felt like a win. I’d come to Miwok with many expectations, but I hadn’t expected it to be nearly this hard, or rewarding or memorable. That’s good enough for me.